The European Union wants Georgia to be a client state, but Georgians appear to have other ideas.

Interview by Anatol Lieven, Director of the Eurasia Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. He was formerly a professor at Georgetown University in Qatar and in the War Studies Department of King’s College London.

Cross-posted from Responsible Statecraft

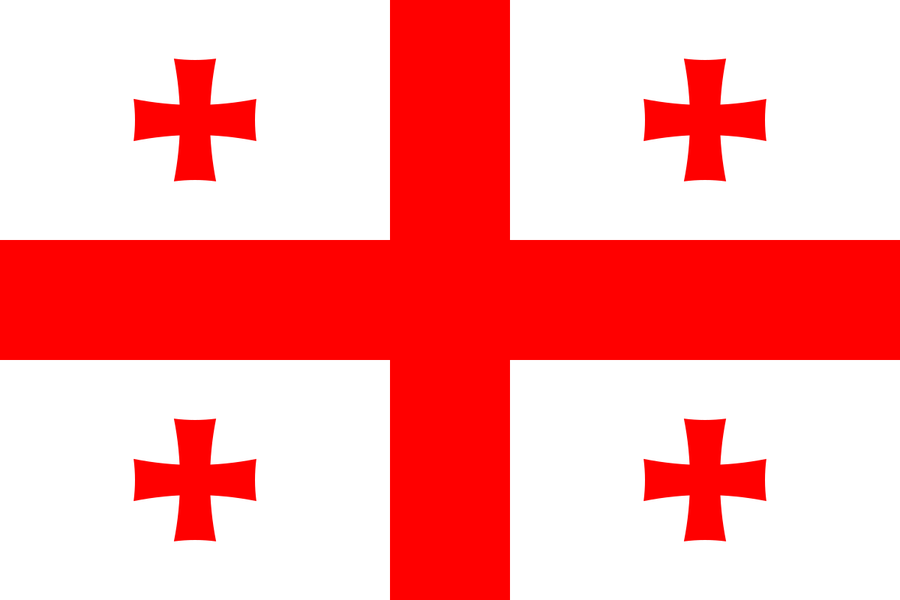

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The European Union expects Georgia to change radically to accommodate the EU. The Georgian government expects the EU to change radically to accommodate Georgia.

The latter may seem an absurd proposition given the relative size of the two sides (and it will certainly be regarded as such by the EU Commission) but as the Georgian President, Mikheil Kavelashvili reminded me in New York last week, Christian Georgia has been around for a lot longer than the EU — almost 1,700 years longer — and confidently expects to be around for a long time after it.

In the years after the Georgian Dream government was elected in 2012, relations with the EU were excellent. The previous United National Movement government of President Mikheil Saakashvili (now in jail for alleged misappropriation of state money), though it had carried out radical economic reforms (backed by copious Western aid), had become increasingly brutal and authoritarian, and had been criticized for this by human rights organizations.

Moreover, though they rarely talk about this in public, Western officials had come to see Saakashvili himself as a reckless and dangerous figure whose actions had brought on the Georgian-Russian war of August 2008, in which Georgia suffered a catastrophic defeat.

Georgian Dream carried out further economic and democratic reforms, and as President Kavelashvili was anxious to stress, as a result Georgia drew far ahead of Moldova and Ukraine in moving towards meeting the EU’s criteria for accession. However, hawkish elements in both Georgia and the West were always suspicious of Georgian Dream’s founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili, a billionaire who — like a number of leading Georgian businessmen — made a fortune in Russia in the chaotic years of the 1990s before moving to France in 2002 and becoming a French citizen. Mr. Ivanishvili’s wealth in 2024 was estimated at between $2.7 billion and $7.8 billion — the latter figure being almost a quarter of Georgia’s GDP. In the view of an opposition activist:

“Georgia currently is ruled by an oligarch who has a very Russian agenda…He owns everything, all the institutions and all the governmental forces and resources. He sees this country as his private property, and he is ruling this country as if it were his own business.”

Mr. Ivanishvili has always been accused by his enemies of being an agent of Moscow, though no concrete evidence for this has ever been presented. What is unquestionable, however, is that Mr. Ivanishvili’s immense wealth, political patronage, extensive philanthropic activities and personal prestige mean that although he was only prime minister from 2012-2013, he remains the Honorary Chairman and dominant figure in Georgian Dream.

In President Kavelashvili’s words, “He was responsible for restoring sanity to Georgian politics and refocusing Georgian policy on our real national interests…The number of people like him in Georgian history can be counted on the fingers of one hand. He is an example to the nation.”

Mr. Ivanishvili’s mixture of immense power with personal reticence and inaccessibility — very unlike the Georgian norm — were among the reasons for the growth of opposition to Georgian Dream in the Georgian political classes. What first drew the EU and NATO into this internal Georgian political battle was the role of Western-funded NGOs, which passionately support EU and NATO accession, but became increasingly linked to the opposition.

Georgia’s relative poverty, and deliberate decisions by previous governments to outsource state functions to them, have given these NGOs an unusually large role in Georgian society and as employers of the Georgian educated classes. Given that their agreements contracts with the EU and USAID generally stipulate a non-partisan role, the government had some reason to think it inappropriate that the EU should continue to fund what had in effect in many cases become openly political groups opposing the government.

However, the government’s moves to regulate the foreign funding of these NGOs caused a storm of protest in Georgia that spread to their backers in Western Europe and the United States, where it was portrayed as the first step in a move to suppress them.

What brought matters to a head between Georgia and the EU was the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The Georgian government condemned the invasion, sent humanitarian aid to Ukraine and imposed certain sanctions on Russia. However, it tried to block Georgian volunteers going to Ukraine to fight and rejected Western pressure to send military aid and to impose the full range of EU sanctions, leading to fresh accusations of being “pro-Russian.”

On this, President Kavelashvili pushed back very strongly. He accused the West of trying to provoke a new war with Russia that would be catastrophic for Georgia. “The West demanded that we get involved in war with Russia against our vital national interests…just like in 2008, when the then government’s unreasonable actions on the basis of trust in NATO led Georgia to disaster,” he said in our interview, adding, “but today, Georgia has a government that represents the interests of our people…the same media outlets that accuse us of being under Russian influence tell the same lie about President Trump.”

President Kavelashvili accused the U.S. “deep state” and organizations like USAID, the National Endowment for Democracy, and the European Parliament of mobilizing the Georgian opposition to this end; “but despite all this pressure, we stood and continue to stand as guardians of Georgian national interest and of Georgian economic growth” — the latter comment a veiled reference to the very important economic links between Georgia and Russia. Western sanctions against Russia have brought about a steep increase in Georgian exports to Russia and the transit trade from Turkey and Europe to Russia, contributing to maintaining high GDP growth over the past three years.

As a result of this clash, and what Western governments allege are the increasingly repressive policies of the Georgian government, several Georgian government figures (including Mr. Ivanishvili) are under Western sanctions, Georgia has paused its application to join the EU, and the so-called “Megobari” Act (in Georgian, Megobari means “friend”), introduced by Rep. Joe Wilson (R-S.C.) to the U.S. Congress with bipartisan support, would if passed by the Senate impose sweeping U.S. sanctions on the Georgian government as a whole.

The Megobari Act, resolutions of the European Parliament and countless articles in the Western media allege that the Georgian parliamentary elections of October 2024 were rigged by the government with the help of a massive Russian “hybrid operation,” although at the time the OSCE observer mission report described them as generally free and without Russian interference, though with government misuse of the media and the civil service to generate support. The elections were followed by large and sometimes violent opposition protests that were met with police violence, and some elements in Europe and Washington support the claim of the former president, Salome Zourabichvili (previously a French diplomat), to remain Georgia’s legitimate president.

Mr. Kavelashvili, however, was defiant. “We are a unique people, and have had to fight for centuries to preserve our language, culture, values and identity,” he told me. “Our overriding aim is to strengthen and preserve this culture…We have an open-hearted approach to the EU and NATO but our relationship must be based on mutual respect. Instead, from them we receive only double standards, hypocrisy and hostility…We aim to join the EU in order to strengthen Georgia, not to weaken it.”

In his emphasis on national identity, national interests and traditional national culture, President Kavelashvili sounded very much like many U.S. Republicans and the growing right-wing populist movements in Europe (and of course the governments of Hungary and Slovakia), which are pushing back against what they see as dictation by Brussels and attempts at compulsory cultural change by liberal elites. As with Georgian Dream, all of these movements are using the language of the defense of cultural values to generate mass support.

This could make President Kavelashvili’s aim to change the EU a good deal less outlandish than it may seem. A future Rassemblement National government in France would probably push for a much looser EU, much closer to the ideas of Georgian Dream — and President de Gaulle — than those of the present European Commission and western European establishments. For in his words, “The European Union is not a museum. Attitudes within the EU are changing, and will go on changing.” Then again, an EU dominated by such forces might also be much less likely to engage in further enlargement. As for most of its history, Georgia would be thrown back on its own resources and its ability to navigate between the contending powers in its turbulent neighborhood.

Be the first to comment