This is truly a remarkable development in Spain. How a small, but committed leftist party can make a phenomenal difference.

Ben Wray is a freelance journalist leading BRAVE NEW EUROPE’S Gig Economy Project. He also produces a morning newsletter called Source Direct on Scottish politics, which you can sign-up to here: https://sourcenews.scot/mailing-list/

Europe’s pandemic has seen lots of paternalistic words about treating workers better in its aftermath, but benign rhetoric doesn’t pay the rent, it doesn’t keep the debt collector from the door, and it doesn’t put food on the table.

Victories do that. Concrete changes in the position of the European working class which can give some confidence to back-up the fragile hope that a wave of unemployment, precarity and social disaster is not the only possible future.

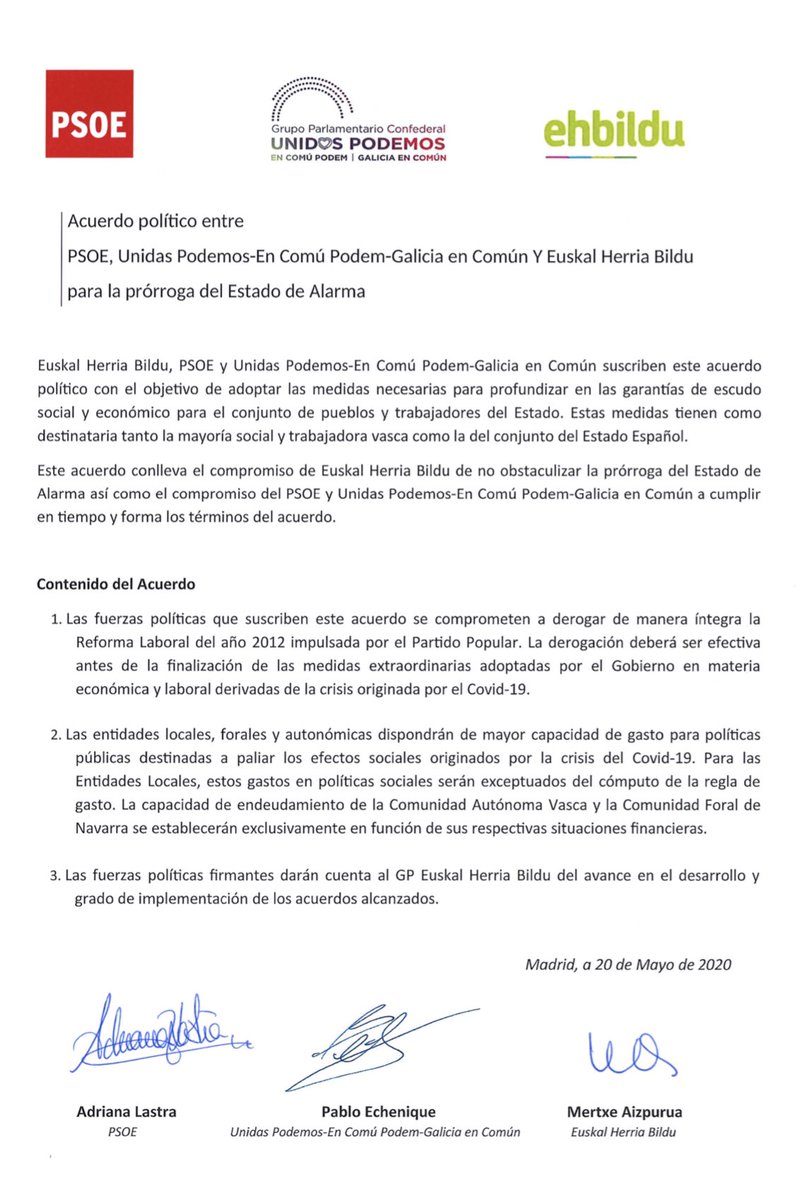

We might have seen such a victory in Madrid on Wednesday. An agreement was unveiled which, according to El Pais, was met with a “general surprise” in the Spanish political establishment. A piece of paper signed by the two coalition government partners, centre-left PSOE and left Podemos, also had a third party, that of EH Bildu, the Basque pro-independence left coalition, with just five representatives in the Congress.

The agreement clearly stated that in return for EH Bildu’s abstention in a vote in the Spanish Congress on the fifth extension of the state of alarm, the government partners would implement the “complete” repeal of the 2012 labour market reforms of Partido Popular, the right-wing Spanish party.

One can tell this has the possibility of being a serious victory for the working class by the response of the employers’ association, CEOE.

Visibly upset, CEOE’s president Antonio Garamendi said he was suspending dialogue with the PSOE-Podemos coalition government forthwith.

The agreement “will have incalculable negative consequences”, which “will have a profoundly negative impact on employment,” Garamendi said.

CEOE had been sitting at every government table for 40 years, be it with the conservatives or social democrats, and “have always found institutional loyalty”, he stressed (as if it was in doubt). But they would sit no longer.

Spain’s neoliberal labour reforms

When the PP introduced labour market reforms in February 2012, they claimed the new laws were designed to facilitate job creation and tackle Spain’s high unemployment. In the first year, 630,000 jobs were lost, the largest increase since the beginning of the crisis. Unemployment reached a historic high of 27 per cent. The Eurozone crisis was at its peak in 2012-13, but regardless: on the PP’s own terms the policy had clearly failed.

In reality, the reforms were always about class power, not job creation. As yesterday’s Basque daily newspaper Gara editorial makes clear: “In addition to deepening the precariousness of labour relations, as all previous reforms had done, the main objective of the 2012 labour reform was to weaken the bargaining power of workers.”

What did the reforms change, concretely? A summary on Eurofound, the EU website for worker analysis, is very clear:

- It undermined centralised collective bargaining, so that “company-level agreements should prevail in a large number of areas”;

- It allowed company bosses to make changes to working conditions “unilaterally”, as long as this didn’t directly contradict collective agreements;

- It made it much easier for bosses to fire workers, by providing an objective criteria that allows for dismissal and reducing pay for unjustified dismissal to just 33 days per year of service

- It brought in a new probationary period contract which lasts one year and allows employers to sack workers in that year without compensation;

- And it changed apprenticeship and training contracts so that they were more flexible for the employer and linked directly to social security discounts.

In the sense that the reforms were an attempt to tip the balance of class forces even more towards employers, they worked. While PP point to the reduction in the unemployment rate to 14 per cent before the pandemic arrived in Spain in February, that is still more than twice the EU average, and disguises the fact that 54 per cent of all new jobs created since 2013 were temporary, according to the National Bank of Spain.

Spain is now second only to Poland as the temporary jobs king of Europe, accounting for 26.1 per cent of all work (Poland, 27.5 per cent). Out of 10.5 million contracts signed in the first half of 2017, only 5.42 per cent were on an indefinite or full-time contract. So when PP leader Pablo Casado claims, as he did yesterday, that the labour reforms “created 3 million jobs”, an unlikely claim, even if that were true, they have now been lost almost as fast as they were created. The same number, three million, applied for unemployment benefit in the first two months of the pandemic.

The need to support workers to support themselves in defending jobs and conditions in this crisis should be obvious, but few would have expected that the breakthrough across Spain would have been delivered via the hand of the ‘Abertzale left’.

Basque nationalist divisions

Euskal Herria Bildu was founded in 2011 and has since cohered the Basque pro-independence left in the post-ETA period, after the armed leftist group declared a permanent cease-fire in 2011 and disbanded in 2018 following a 50-year bloody conflict with the Spanish state.

Eh Bildu is a strong force in Basque society, strongly rooted in local communities with over 1,000 councillors. It came third in the November General Election, with 18.7 per cent of the vote. But for the increasingly hysterical Spanish right, radicalised by the rapid growth of far-right Vox, Bildu is the devil in thinly-veiled disguise. The longer since the end of ETA, the more the right try to wish their favourite bogeyman back into existence. Fear is central to their discourse.

Thus, the surprise deal on Wednesday was a historic moment in Spanish politics – it was the first time EH Bildu and two parties of the Spanish state had signed an agreement on a question of legislation. It’s significant that deal was over a straight-forwardly class issue, rather than constitution, and the Abertzale left (Patriotic Left – the parties or organizations of the Basque nationalist/separatist left, stretching from democratic socialism to communism) has used its new found credibility in Madrid to reach a hand out to workers across the Spanish state.

“I want to send greetings to the entire working class of the Spanish State,” EH Bildu General Secretary Arnaldo Otegi, said. “What unites us with the Spanish working class is not belonging to the same nation, but to the same class.”

The text of the agreement reads: “The political forces that sign this agreement are committed to fully repeal the Labour Reform of 2012 promoted by the People’s Party. The repeal must be effective before the end of the extraordinary measures adopted by the government in economic and employment matters arising from the crisis caused by the COVID-19”.

It also has an additional clause which upends caps on spending and borrowing in the Basque Country. For a party with just five seats out of 350 and that is treated as Satin by the Spanish right, and with the price being only an extension to the state of alarm for 15 days, the deal is quite a coup.

And it has unsettled other forces in Spain’s complex, fragmented political scene. The Spanish right are apoplectic, though that is a given. The Catalan pro-independence parties in Congress, including ERC, an ally of EH Bildu, voted against the state of alarm extension, angry that devolved powers have been usurped in the lockdown period by President Pedro Sánchez, and that the issue of Catalan political prisoners and democratic rights has been deliberately kicked into the long-grass. But perhaps most significant is the reaction of the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), coalition partners of PSOE in the Basque Autonomous Community and used to being the only Basque nationalists to have a seat at the table in Madrid. They had been supporting the PSOE-Podemos coalition, but have suddenly been put in the shadow of their smaller left-wing rivals, ahead of an election in July.

“I advised Sánchez that, in the middle of the river, it is not good to change horses,” Andoni Ortuzar, President of PNV, said following the agreement, “the good disposition of the PNV is alienated”.

PNV’s problems are racking up. The party – of a conservative, christian-nationalist political tradition – has played a dubious role in the pandemic, which has hit the Basque Country very hard. While EH Bildu were calling for the stopping of all non-essential work in March, PNV’s head of Institutional Policy, Koldo Mediavilla, was describing those arguing to put health first as “demagogues who only talk about rights and never duties” and who “want to change the economic model”.

After the “demagogues” won and a full lockdown belatedly began, the party of Basque big business has sought an early return to work and school at every stage. Meanwhile, the decision of PNV to push forward with the election on 12 July despite the health situation remaining precarious also looks like opportunism for electoral advantage. Set against EH Bildu winning what appears to be a significant victory for workers’ rights, the election begins to be framed as a battle along class lines – worker v capitalist; health v profits.

The calculation of PNV is that the lockdown conditions give them the opportunity to dominate TV while parties of the left, more reliant on activism, will struggle to campaign on-the-ground. Additionally, the worst of the economic crisis has still not worked its way through the Basque economy. Time will tell if PNV’s gamble pays off, but while they may have the upper-hand institutionally, they appear to be losing control of the debate narratively.

Not over the line

EH Bildu knows not to count their chickens before they are hatched. PSOE are notorious for turning their back on agreements, and there were signs just hours after this one was signed that the left party of the Spanish political establishment was nervous about what they had just agreed to. “Vertigo,” was how El Pais described it.

PSOE issued an “explanatory note” to the press about the agreement, which led some government Ministers to suggest that the deal to completely repeal of the labour reforms was being “rectified”; i.e. watered down. What all this means is not exactly clear, but Podemos and EH Bildu say nothing has changed.

“The parties can say what they want,” said Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias. “What was signed was what was agreed. The deal between the three parties is to completely overturn the reform.”

Otegi echoed Iglesias: “’Pacta sunt servanda’ (what is signed, obliges)”.

“We are not in politics to accept things that cannot be changed,” he added. “We are in politics to change things that cannot be accepted.”

The reforms still have to get through the Spanish Congress in which even the combination of PSOE, Podemos and EH Bildu is not enough for a majority. There are other parties of the left which will definitely support it; the real danger to the repeal comes from PSOE, the dominant party in the coalition that has frustrated Podemos’ efforts at pushing through serious reform so far.

If the repeal does go through in full in the end (a big if), it could be the most significant change delivered by the PSOE-Podemos coalition – which has handled the Covid-19 crisis very badly – so far. Albert Medina Català, economist at Catalan innovation co-operative Ekona, says the repeal “opens the Pandora’s box of labour market regulations”; we should be on guard to ensure that what replaces it is actually a step forward.

“It will be important for the working poor – gig economy workers and others – to put all the efforts in introducing their own agenda in the future tripartite negotiations where a new agreement will be prepared,” Català argues. “That is the main challenge of the working poor, that are historically unrepresented in the Spanish industrial relations and in this type of negotiations. “

In the end, it will take a lot more than rolling back neoliberal reforms to get Spain through its most severe crisis in the post-Franco era, doubly so when castrated by the macro-economic mismanagement of the Euro. But at least it would be a start, and one where the role of the Basque pro-independence left was undeniably crucial.

Be the first to comment