The success of populist parties is often viewed as an act of protest against ‘the establishment’. Drawing on new research, Bram Geurkink, Andrej Zaslove, Roderick Sluiter and Kristof Jacobs illustrate that this may not always be the case. Voters for populist parties are not just protest voters: when they have the opportunity, they vote for an alternative.

Bram Geurkink is a PhD candidate in the Economics Department at the Institute for Management Research at Radboud University

Andrej Zaslove is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at the Institute for Management Research at Radboud University

Roderick Sluiter is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Economics Department and Lecturer in the Political Science Department at the Institute for Management Research at Radboud University

c is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department at the Institute for Management Research at at Radboud University

Cross-posted from LSE-EUROPP

Populist parties are ever more popular: over the last two decades they have more than tripled their vote share in Europe. This has been illustrated by the rapid rise of parties such as the Lega in Italy, La France insoumise in France or the Forum voor Democratie in the Netherlands. Beyond elections, populism was also visible in the Brexit referendum and the French Yellow Vests upheaval.

It is tempting to view this rise in populism simply as a form of protest: a signal against established politics or even protest against democracy as such. Yet as new research we have carried out suggests, support for populist parties signals not just protest, but also a desire for a particular alternative: one where politics is more in line with what ‘the people’ want.

Citizens can also have populist attitudes

The concept ‘populism’ is often ‘thrown around with abandon’, typically to label a political opponent or someone one does not agree with. As a consequence, readers might get the feeling that populism is everything and nothing.

Yet this is not the case. Most scholars agree with the prominent populism scholar Cas Mudde that populism refers to a set of ideas “that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.

When we think of populism, we typically think of populist parties. But it’s not just about parties. Citizens can also adhere to the set of ideas Mudde pinpointed as the core of populism. Indeed, they can to a differing extent (dis)agree with the idea that elites are corrupt, the people are good and that politics should be the expression of the general will of the people. Such populist attitudes amongst citizens, in turn, can constitute fertile soil for voting for populist parties, but also change referendum dynamics or trigger protests such as the French yellow vest protests.

Populism is different from just being anti-establishment

Some might say that the definition of populist attitudes sounds an awful lot like simple anti-establishment feelings. One might even wonder: is this new notion of populist attitudes not just old wine in a new bottle?

To a certain extent, this makes sense. Specifically, citizens with a high degree of populist attitudes may simply have low political trust or believe that politicians do not listen to them (i.e. a low ‘external political efficacy’). However, at a theoretical level the three concepts are related, but different. They share what they are against (i.e. the establishment), but of the three concepts only populism also includes an explicit alternative: it wants politics to be an emanation of the people.

The real-life consequences of populist attitudes

The two anti-establishment measures, trust and external political efficacy, are thus at least partially different from populist attitudes at the theoretical level. And this matters: the causes of a lack of trust in politics, for instance, may well be different from those of populist attitudes and so may their consequences.

To examine this, we conducted a series of analyses relating the anti-establishment measures and populist attitudes to voting for populist parties and non-voting – one of these potential consequences. We analysed the extent to which political trust, external political efficacy and populist attitudes are conceptually and empirically different concepts and the extent to which these attitudes are able to explain voting for three populist parties. We used the Dutch NRO2018 dataset (March-April 2018), which includes a sizeable number of respondents for each of the three populist parties. This is especially relevant regarding the new populist radical right party Forum voor Democratie, as most datasets, such as the 2017 national election survey, stem from the time when the party was still relatively small.

Our dataset covers the Dutch case, which is an excellent case to study our topic because it has a wide array of populist parties. Most importantly it has a successful left-wing and two right-wing populist parties. It is thus the perfect context to examine the impact of anti-establishment measures versus populist attitudes in a clean way.

Trust is linked to non-voting, populist attitudes explain voting for populist parties

Our analyses reveal that populist attitudes indeed seem to have different consequences. Whereas anti-establishment feelings, and in particular political trust, seem to increase the likelihood of abstaining from voting, this is not the case for populist attitudes. Citizens with stronger populist attitudes are, all else being equal, not more (or less) likely to stay at home than their counterparts with weaker populist attitudes.

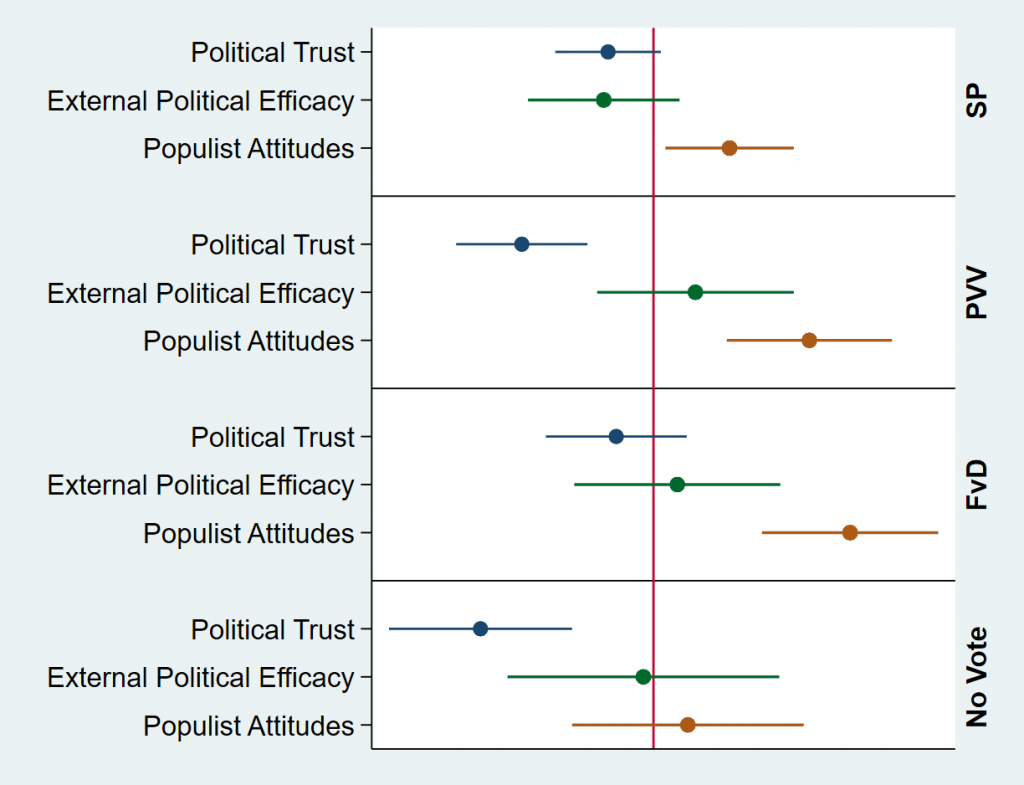

Figure 1: Effect of political trust (blue), external efficacy (green) and populist attitudes (orange) on voting behaviour

Note: Dataset: Nationaal Referendumonderzoek 2018 & Politics and Values (CentERdata); N=1351 ; Dots indicate the standardized coefficients of a multinomial regression analysis with voting for a non-populist party or blank/invalid voting as reference category. The lines represent confidence intervals (95%); if these lines overlap with the vertical red line, the effect is statistically insignificant. These effects are controlled for by education level, sex, age, and economic, cultural and EU attitudes.

However, we do show that citizens with stronger populist attitudes are more likely to vote for a populist party. Again, this illustrates that voting for a populist party might not just relate to being against something, but also to being in favour of something. Voters for populist parties are not just protest voters. When they have the opportunity, they vote for an alternative.

The difficulty when addressing populism

For a long time, voting for populist parties was seen simply as a protest vote. While there is an element of truth in this, our findings question whether this is fully the case. They suggest that populism is not just about what is wrong with politics, but also offers a worldview outlining how politics should be. The focus on returning power to the people not only separates populism from pure anti-establishment voting, but may also have implications about discussions surrounding political representation; i.e. debates surrounding referendums and citizens’ assemblies.

Not surprisingly, when faced with protests by the Yellow Vests, French president Macron suggested holding a referendum and a ‘great debate’. In theory, such actions could appease citizens with populist attitudes, but it remains to be seen whether such citizens are convinced that somebody from within the establishment is able to bring them the change they seem to desire and thereby represent the will of the people.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Political Studies

Be the first to comment