The Catalan independence movement has become bogged down in internal political divisions. The movement lacks a progressive vision capable of mobilising a large majority of Catalans, resorting instead to portraying itself as a victim.

Chris Bambery is author and broadcaster. Co-author (with George Kerevan) of Catalonia Reborn: How Catalonia Took on the Corrupt Spanish State and the Legacy of Franco (Luath Press, June 2018)

Just six months ago the advent of a minority Socialist government in Madrid, headed by Pedro Sánchez, seemed to point towards dialogue with its Catalan counterpart in Barcelona. After all Sánchez had depended on Catalan votes to topple the corrupt Popular Party government of Mariano Rajoy after moving a vote of no confidence. Sánchez still requires those same votes to remain in office, in particular to pass a budget for 2019 through parliament. Concessions have been made: the nine Catalan political prisoners were transferred from jails outside Madrid to ones in Catalonia and Sánchez has met the Catalan president, Quim Torra, opening hopes of sustained dialogue.

But those same prisoners will, in a matter of weeks, stand trial on charges of rebellion and sedition before the Constitutional Court, with its tranche of judges politically appointed by the previous Rajoy government, demanding sentences of 17 to 25 years. The Attorney General insists those charges will not be dropped.

When Rajoy played hard ball with the Catalans after the Barcelona parliament approved the 1 October 2017 independence referendum – sending in paramilitary police to physically stop it, arresting politicians and civic leaders and suspending Catalan’s Statute of Autonomy – the Socialists backed him. There was little to distinguish between the Rajoy’s conservative Partido Popular and the centrist Social Democrats.

Today many Catalans view Sánchez as the soft cop who worked in tandem with the hard cops of the right-wing Partido Popular.

But something has changed in Spain. When the Partido Popular lost office to the Social Democrats back in 2004, and the Scoial Democrats began negotiations culminating in a new Statute of Autonomy giving greater powers to Barcelona and recognising Catalonia as a nation, the Partido Popular under Rajoy used anti-Catalan sentiment to rebuild its support; petitioning on the streets, holding rallies where Spanish nationalism was on display in full force, calling for boycotts of Catalan sparkling white wine, Cava, and challenging the new statute to the Constitutional Court.

In 2010 the reactionary Constitutional Court removed key elements of the Statute, including the definition of Catalonia as a nation, bringing over a million people onto the streets of Barcelona in protest. Overnight support for independence rocketed. It was a crucial moment.

The Partido Popular cannot drop its anti-Catalan agenda, but quickly found it was facing competition from the even more neo-liberal Ciudadanos party, founded after the 2008 economic crash to remove endemic corruption and to “reform” Spain’s economy. By October 2017 Ciudadanos was attacking Rajoy for being too soft on Catalonia, targeting the autonomy of the Basque Country too.

Today both parties face another competitor even further to the right in the shape of the openly Francoist Vox party. At the beginning of December 2018 it won 12 seats in the Andalusian regional elections. Formerly a bastion of support for the Socialist Democrats, they lost political control of the region and now an right alliance of the Partido Popular, Ciudadanos and Vox will govern Andalusia. Despite that alliance, all three are competing as to which is more robustly opposes Catalan independence and which represents Spanish nationalism best. The Social Democrats are not immune from that pressure, boasting of their unionist credentials.

So going into 2019 Spanish politics has rapidly moved rightwards, with fascism emerging as a serious force for the first time since General Franco’s death in November 1975. That is why I would argue there can be no compromise, with Madrid approving a referendum in Catalonia on independence.

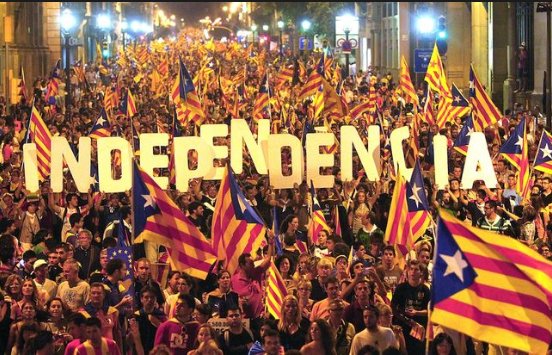

In Catalonia the three independence parties are fighting among themselves, but the pro-independence mass movement which has existed since 2010 is a force in itself. They have a clear focus in the defence of its leaders being held as political prisoners by the Spanish government, 18 of 19 of whom, will be in the dock together in a few weeks’ time. It will look like a show trial and the Catalans will point insistently to the fact that charges of rebellion and sedition have been removed from the statute books elsewhere in Europe and to the lack of judicial independence in Spain because of government appointments to the bench.

Some 80 percent of Catalans oppose these trials and the preventative detention of nine of the key suspects. That anger was clear with the scale of the protests which greeted Sánchez, when he held a provocative Spanish Cabinet meeting in Barcelona just before Christmas. Those protests had a harder edge because they were also in support of creating a Catalan Republic. If the nine political prisoners receive sentences of 17 to 25 years for organising the independence referendum anger must increase.

The verdict might not be reached in time for European and municipal elections due across Spain in a few months time. Not long ago there was particular concern over the outcome of the mayoral election in Barcelona with fears Ciudadanos might gain the biggest vote as the pro-independence parties were divided, but today the unionist camp is divided too and there is little certainty about the outcome.

Somewhere around 50 percent of Catalans do not back independence, but feel alienated by a Spanish state which has denied them democracy and meted out repression. It seems that support for the Catalan political prisoners has mobilised many who did not previously support independence but are now being won over.

A further ground for discontent in Catalonia is in play: the 2008 financial crash and the devastating recession which followed. Successive Spanish governments of the centre and the right had allowed a property boom to play out over two decade creating a domestic subprime mortgage crisis. The chickens came home to roost in 2008, leaving many Spaniards with massive debts and no legal means for a personal insolvency.

The close ties between Spanish politicians, finance and big business (see here), and the corruption which flourished, lead to widespread anger, but in Catalonia it reinforced the view that escape from the Spanish state was necessary.

Today both the Madrid government and the EU proclaim that Spain has escaped the past ten years of grim austerity and is marching forward to new prosperity, creating record numbers of jobs. Yet reality tells a different tale.

Today the biggest employer in Spain is tourism, having over taken construction. It employs 2.65 million people, 13.7 percent of Spain’s working population. Yet these are low paid jobs, in 2016 (the last year for which statistics are avialable) employees in the hospitality sector were paid on average €9.32 an hour, less than €11.73 received by conxstruction workers. Because of the seasonal nature of tourism many of these jobs are temporary with 35.2 percent on short term contracts.

These are jobs highly vulnerable to an economic downturn in the Northern European nations, where most of the tourists come from, and a subsequent fall in the number of visitors

Despite the rise in employment, the number of workers in Spain at risk of serious poverty stood at 13 percent in 2017. Last year two thirds of part time workers were seeking a full time job, as a consequence of underemployment.

This is particularly true for younger workers. Between 2008 and 2016 all employees suffered an income decrease, but the youngest suffered more; with a 28 percent reduction for teenagers, 15 percent for 20-24 year olds, and 9 percent for 25-29 year olds. In 2005 6.7 million 20-29 year olds were registered as in work. By the start of 2018 the figure was just 4.8 million, a contraction of 30 percent.

According to the CCOO trade union federation the number of under-30’s working on hourly contracts has risen to 27 percent. Overall unemployment has reached nearly 40 percent among under-25s. The figures are highest in the traditionally poor south.

As the economic clouds darken globally, especially in Europe, so too does concern that the Spanish economy is very vulnerable to any downturn. Catalonia has done better in attracting transnational investment and in helping small and medium companies, particularly in high tech industries, but it remains tied to the Spanish market as does the future of its economy. Fears for the future can only increase the belief that Catalonia can do better on its own.

Overall it seems there is little chance of compromise, but one thing has changed, Back in the dark final years of the Franco dictatorship the centre of resistance was in both Catalonia and the Basque Country. With the transition to democracy both grew apart, particularly as ETA continued its military campaign. The mainstream Basque National Party ran the government there and was very cautious, giving its support to Rajoy until they recently turned against him to support the vote of confidence earlier this year.

Today ETA and its violence are history. Radical nationalism has re-emerged as a force after Spain’s attempts to ban such parties and its policy of imprisoning its leaders has run out of steam. That means the Basque Country has seen major protests in support of Catalonia. The moderate Basque Nationalists are aware Spanish nationalists are targeting their autonomy and the emergence of the ultra-right Vox revives bitter memories of how Franco tried to assert Spanish unity by trying to destroy the culture and language of the Basque lands and Catalonia.

Even if the Catalans and Basques come together in demanding Spain lifts sanctions on independence referendums – what is a very remote possibility – they would be numerically too weak to change the law.

And there is one last element. Catalans bitterly remember the silence of the EU in October 2017 when Spanish police were sent in to smash their way into polling stations, to seize ballot boxes and truncheon voters. The EU political elite remains silent, but across the EU there is growing disquiet over its support for Madrid. Many see that as having threatening consequences for human rights in their own nations, others look at repression in Catalonia and raise valid concerns over the neglect of human rights by the EU. this my have put pressure on the European Commission and on Madrid, but they are clearly sitting this out.

Will there be a resolution of the Catalan question in 2019? I would answer no. But there is one other wild card, Scotland. The independence movements in Catalonia and Scotland see themselves as walking forward in common destiny. Given the current Brexit turmoil in the UK, a second Scottish independence referendum cannot be dismissed, and support for independence is growing. If, and it remains a big if, Scotland achieves independence I believe Catalonia would follow soon.

Be the first to comment