We admit this is a very long read, but it does explain very well the property crash in Spain, the corruption in Spanish banks, and how they too capitalised on the crisis to increase their power at the expense of Spanish citizens and democracy.

The Congressional Commission of Inquiry into the financial crisis in Spain has come to an end. Should the conclusions not be published, the causes of a crisis from which we have not yet emerged can already be analysed.

Sergi Cutillas is an economist and worked in the financial sector before taking up his work as a financial justice activist in early 2012. He is a member of the European Research Network on Social and Economic Policy.

Josep Vendrell, historian, is a member of the Spanish Parliament and spokesperson there for En Comú Podem (Catalan coalition allied with Podemos). Previously, he was a member of the Catalan Parliament for United and Alternative Left (ICV-EUiA). He has participated in the investigation commission on the financial crisis of the Parliament of Catalonia (2013-14) and the investigation commission on the same topic of the Spanish Parliament (2017-2018).

The Spanish Parliamentary Commission to investigate the financial crisis in Spain and the following rescue programme, which began its inquiry on 11 May 2017, has just concluded its work. Representatives of credit institutions, regional, state, and European regulatory and supervisory institutions, politicians who participated in the management and administration of institutions or who took important decisions in relation to the crisis, technicians, academics, researchers, and also representatives of those affected by the poor practices and frauds of these entities, appeared before the committee.

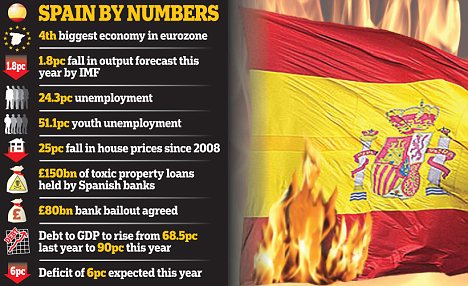

It has led to the conclusion that the policies carried out by those responsible for the Spanish financial system have been responsible, together with international factors, for causing the crisis of the financial system, which in turn led to an economic crisis that has done enormous social damage, especially among the poorer sections of Spain´s population, which translated into high levels of unemployment, poverty and inequality. In addition, such practices have affected hundreds of thousands of families through the loan and savings products they contracted with these entities, collectively violating their rights as consumers. In addition, the process of restructuring the financial sector following the bankruptcy of these institutions, which has led to increased concentration of the sector and the virtual disappearance of Spanish savings banks, has imposed tremendous costs on the nation´s citizens. The public money injected into financial institutions that has not been repaid, exceeds 60 billion euros.

The regional oligarchies, and to a lesser extent state oligarchies, had intervened and in some cases appropriated the governing bodies of the credit institutions, especially the savings banks, to use them for their own political and economic benefit. A part of these regional elites were business people with ties to the credit institutions, especially of the property and construction sectors. They carried out operations that did not correspond to market conditions. Another part were elected politicians, often from autonomous governments, who used their influence and/or presence in the governing bodies to obtain outrageous remunerations and/or political incentives, which made it easier for the directors of credit entities to provide their regional governments with dubious finances and often fraudulent financing of real estate agents.

For their part, the large savings banks of Madrid and Barcelona, Caja Madrid and La Caixa, created portfolios of large strategic companies, becoming members of the boards of directors of the large companies of the Ibex 35. Their objective was to create major business conglomerates that would grant political and economic power to those who controlled these financial entities. In the case of Caja Madrid, this was one of the causes for its aggressive investment and credit expansion strategy and its subsequent collapse. Bankia, an entity that emerged from the merger of financial institutions during the restructuring of the sector, of which Caja Madrid was a majority shareholder, would be nationalized and forced to divest its portfolio of companies as a condition of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the EU of 2012. La Caixa, despite the decrease in its portfolio of holdings, has come out of the crisis stronger and able to maintain its great influence after the crisis already having been converted to a universal bank.

The responsibilities for the crisis therefore fall on the members of the administrative and management bodies who, with their decisions, ruined the sector and deceived clients: those external businessmen who sought favourable treatment, and on the political and supervisory institutions, who did not intervene to prevent this from happening, and who in many cases took part in the irregular practices and illegal activities that led to their bankruptcy, by action or looking the other way.

The commission investigated these practices with the aim of identifying the specific persons responsible for generating the crisis, so that they can compensate the Spanish citizens for the damage they caused. It was also necessary to analyse the institutional model that has allowed this great scam, in order to distance ourselves from it so that this does not reoccur in Spain. The rest of this article will mention some of the conclusions and findings of the commission briefly, given that the opinion of the parliamentary group of Unidos Podemos-En Comun Podem-En Marea on which it is based contains more than 350 pages.

The financial crisis was the result of financial deregulation and liberalisation in the field of housing and urban development, promoted since the beginning of neoliberalism in Europe in the mid-1970s, and the subsequent entry of Spain into the European Economic Community in the mid-1980s. Various regulatory changes facilitated such a dynamic of cooperation between political parties and financial institutions, especially in the savings banks sub-sector, through the deregulation of their credit activities and the authorisation of their territorial expansion outside their place of origin. This initial process, known as ‘bankarisation’, was aimed at enabling savings banks to compete in the same market as Spanish and European banks.

The commission has also found that there was excessive exposure to the real estate market by credit institutions. These institutions participated actively in this market, very often through the creation of companies, in which they held an interest, that acted as real estate developers, providing them with loans. In the mid-1990s, the weight of the real estate sector credit was 31% of the total credit to the resident private sector and 59% in the case of savings banks. In 2009, the weight of real estate loans had risen to 57% for banks and 74% for savings banks. In the case of banks, growth was mainly due to loans to developers, which rose from 4% to 18% in that period, while for savings banks it rose from 5.5% to 21%.

It should be noted that large inflows of international credit increased sharply with the entry into the euro in 1999. The euro caused a persistent current account deficit in Spain. Any monetary union between nations needs the stable maintenance of real exchange rates. This means that the variation in prices in the different regions must correspond to the productivity gains of each region plus a common inflation target, which in the case of the Eurozone ought to be the inflation target of 1.9% included in the ECB’s price stability mandate.

Germany, from the end of the 1990s onwards, did not respect this agreement and kept wages significantly below this index (the evolution of wages has an almost perfect 1:1 correlation with the evolution of prices), while Spain and other peripheral countries surpassed this index. This divergence between Germany and the rest led to a devaluation of the real exchange rate in Germany, which made it easier for Germany to become a major exporter of goods and capital to its neighbours in the euro area. In the case of Spain, such external deficits were financed through credit captured in wholesale markets, which was used to inflate the real estate bubble.

One of the outstanding examples of the blunder carried out by the entities in the real estate sector was the creation by Caixa Catalunya of a conglomerate of real state agencies at the same time as it was dedicated to granting mortgages to those same companies, which it did with massive financing. According to statements by its former director, Adolf Todó, in the investigation commission of the Parliament of Catalonia carried out in 2013-14, Procam, the real estate conglomarate company “was one of the five largest real estate conglomerate companies in Spain. Through this conglomerate of 80 subsidiaries, 4,500 million euros were invested in development activity in Spain and abroad”.

Another example of this was the Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo (CAM) in the period between 2001 and 2008. According to official figures, the institution had a risk of between 11 and 16 billion in loans to real estate development companies. CAM had a stake in up to 66 companies and 104 projects linked to the real estate sector. In those years, according to statements by its own ex-managers, the bank guaranteed loans to builders with a simple rustic plot of land, assuming that in a couple of years its price was going to multiply as a result of speculation and reclassification as building property.

This whole process was carried out with the approval of regulatory and supervisory bodies in Spain and the ECB at the European level, which were found to be aware of the enormous risk posed by the crony credit model centred on the real estate sector. This situation can only be explained by the capture of the regulatory bodies by the interests of the political and economic elites, in a similar way to what happened in the savings banks and banks themselves by the regional and local elites.

This dynamic was reinforced by the growing participation of private external audit firms in credit risk assessment, and consulting firms that strategically advised entities, generating a total lack of transparency and creating situations of conflict of interest. Companies such as Deloitte and KPMG have been sanctioned in Spain for having carried out infractions considered “very serious” and “serious” in their audit activity of credit entities. Others, such as Boston Consulting Group (BCG), to which Caixa Catalunya outsourced its strategic decision-making, were not sanctioned despite the enormous damage to the institution and to the sector caused by its advice, given that its decisions contributed to the inflation dynamics of the bubble and led to the bankruptcy of Caixa Catalunya.

Much of the credit expansion was carried out through the granting of loans whose liquidity came from wholesale credit markets, through the issuance of debt securities of the financial institutions, many of which were mortgage-collateralized bonds. The issuance of debt securities was made with a significantly shorter return term than the parallel mortgage loans that served as collateral.

The credit entities carried out an aggressive policy of attracting clients among vulnerable sectors, offering mortgage loans under questionable conditions and hybrid instruments whose risk clients could not understand.

During the period prior to the crisis, mortgage loans were granted without verification of income and income was not verified. Nor was the information from the Risk Information Centre used to determine the suitability of clients for borrowing. In addition, mortgages were given to those who had no previous savings capacity. Employment security was not considered as a criterion either, given that loans were granted with proof that a salary had been received in the last month. Faced with rising house prices and in order to have mortgage loans with a low monthly payment, the terms were extended to over 30 or 40 years or even up to 50 years.

Subsequently, when the crisis began, the banks and savings banks, faced with default and non-payment of mortgage payments, began an aggressive campaign of foreclosures, many of them based on abusive clauses that protected their interests. According to data from the National Statistics Institute and the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ), since the beginning of the crisis in 2007 and until 2017 there have been about 750,000 evictions and 585,000 foreclosures. Fifty-five per cent of foreclosures initiated on housing correspond to mortgages constituted between 2005 and 2008. The entities deployed an aggressive strategy of judicial persecution against mortgage debtors in order to enrich themselves and take advantage of their clients, protected by a tolerant neoliberal policy of self-regulation and non-invasive vigilance. This flagrant aggression was carried out with the approval of the regulatory authorities of the Bank of Spain and the Ministry of the Economy who failed to protect consumers from the execution of abusive clauses in hundreds of thousands of mortgage contracts.

In the case of hybrid bonds, their marketing was a premeditated scam to absorb customer savings in order to compensate for the losses that had emerged due to the restructuring process in the sector, all with the consent of the regulators. In fact, as Andreu Missé has explained in his book “The big scam of the preferentials”, credit institutions placed more than 14 billion euros in preferential shares among their customers between October 2008 and September 2009, when the interbank market got frozen, all with the acquiescence of the Bank of Spain. For the authorities, the priority was to ensure the solvency of banks and savings banks, albeit at the cost of deceiving savers into paying the losses of the credit institutions out of their own pockets. In fact, they were the first in Europe to suffer a bail-in (the internal bailout carried out with the money of the investors and savers of the same bank, which was also subsequently applied in the resolution and sale of Banco Popular), when in 2011 they saw that they could not pay out their client´s savings, that these were forcibly converted into shares. The 2012 EU Memorandum of Understanding was the basis for inflicting further write-offs, which were applied to savers trapped in these products, which in some cases reached 70%. In Spain, the total sanctions imposed by the CNMV were ridiculous compared to the total volume of preferred shares and subordinated debentures traded among small savers until 2013, which amounted to more than 42 billion euros.

Another case worth mentioning was Bankia’s flotation on the stock exchange in July 2011. Bankia, an entity born out of the merger of prominent savings banks such as Caja Madrid in the first round of rescues and mergers carried out in 2010, promised, under the presidency of the brand new Rodrigo Rato, to be a modern and solvent entity that could face the future with hope. The entity came out at a price of 3.75 euros per share, for which it captured 3,092 million euros. In just one month the share plummeted more than 80%. 60% of investors were retailers with investments between 5,000 and 6,000 euros. The Government’s responsibility in this case is clear, given that it approved a decree in February 2011 that made it possible for Bankia to go public. The authorities (CNMV, Bank of Spain and Ministry of Economy-FROB) had accepted the financial statements presented by Bankia in the IPO prospectus. The former president of Bankia himself explained the close relationship between the FROB and Bankia. According to Rato, the FROB approved its plans, including its accounts, on a quarterly basis. However, at the end of 2012, with the share value close to zero, the FROB had to inject another 18 billion euros to clean up and nationalise the bank.

For its part, the board of Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo falsified its accounts with the aim of looting the entity through the collection of illegal bonuses in the millions linked to the banks “profitable business” and early retirements , when it was technically bankrupt. Its property transactions were also carried out through an affiliated company, which it financed to build and acquire hotels and property in the Caribbean, mainly in Mexico and the Dominican Republic, and with which funds were diverted to other companies located in Caribbean tax havens. On the other hand, the former president of the entity Modesto Crespo has admitted the irregularity of the payment of allowances of 300,000 euros per year through an affiliated company, accepting 9 months in prison as the author of an aggravated misappropriation offence.

The last case we should mention is that of the resolution and sale of Banco Popular to Santander for one euro in June 2017. The process was supposedly carried out due to a liquidity crisis of the bank, but on the other hand the declarations of the directors and regulators in the months prior to its bankruptcy questioned its solvency, generating fear and uncertainty that caused the flight of deposits that killed the bank. In fact, by March 2017, the bank had barely lost any deposits compared to the previous year. On the other hand, all the external and internal audits, as well as the stress tests of the EBA showed that the bank was solvent. In spite of all this, and without even having begun the critical phase of flight of deposits that supposedly killed the bank, on May 31 Reuters reported that the president of the Single Board of European Resolution, the German politician Elke König, warned the European authorities that the Popular “could be liquidated if it does not find buyers”.

In retrospect we now know that the Spanish public administrations withdrew hundreds of millions of euros deposited in Banco Popular during the critical days of its liquidity crisis. In addition, the resolution and sale took place on Tuesday night, June 6, but the flight of deposits began in the previous week, so that already with a liquidity coverage ratio below the permitted level, supervisors allowed the Popular to open its doors on Monday. The following day the ECB declared that Popular “will or is likely to fail”, so the Bank Resolution Board launched an express auction that same night after the close of the markets, based on a report by an independent expert, Deloitte, which stated that its value was negative, between 8.2 and 2 billion euros. This represents a difference of at least 13 billion and a maximum of 20 billion euros between the external evaluation and the bank’s accounts as of March 2017, which declared a positive net worth of more than 11 billion euros. The resolution carried out by the Single Eurozone Bank Resolution Mechanism and the Spanish authorities involved a bail-in of a total of 6 billion euros in shares and 2 billion in convertible, preferential and subordinated bonds in the sale process to Banco Santander. Coincidentally, the valuation of Deloitte, which remained secret until a few months ago and was only partially made public, allowed for a clean bail-in in which the senior debt and depositors’ money was not touched. The operation was coordinated first-hand between De Guindos and König. The resolution strengthened the credibility of the Banking Union, scored points for De Guindos, who is now vice-president of the ECB, and above all, allowed the consolidation of the sector to continue in favour of Banco Santander, which absorbed one of the traditionally most successful banks in the field of medium-sized corporate banking for only one euro, after itself being recapitalized by its own clients and shareholders.

In short, it can be concluded from the committees investigation that ´Spain´s financial system needs a profound rethink, so that the profit and economic benefit of managers are no longer influencing policy, and in which financial regulation limits the activities of credit institutions. This requires credit institutions to acquire a public and democratic character. It is also clear that a profound reform of the state administration is necessary, especially of the sector’s regulatory and supervisory bodies, so that their capture does not happen again. It will also be necessary to remove from the hands of private agents the role of appraisal, risk rating, and audit to avoid the opacity and conflict of interests present in this crisis. Finally, it will be necessary to eliminate the economic neoliberalism embedded in the European institutions, given that the architecture of the euro has generated the imbalances that have led us to the crisis, and the austerity corset imposed in its treaties does not allow Spain to get out of it.

Be the first to comment