This is an interesting contribution in our ongoing debate about Modern Monetary Theory.

is the author of the Coppola Comment finance and economics blog, a contributor to Forbes and the Financial Times and other publications. She is currently Managing Editor of an important content marketing campaign for a major financial institution with Contently.com.

1. Issues its own currency exclusively

2. Requires all taxes and related obligations to be extinguished in that currency

3. Can purchase anything that is for sale in that currency at any time it chooses, without financial constraints. That includes all idle labour

4. Its central bank sets the interest rate

5. The currency floats

6. The Government does not borrow in any currency other than its own.

This appears solid. But in fact, it too is wrong.

The only country in the world that can always buy everything the country needs in its own currency, and therefore never needs to borrow in another currency, is the United States, because it is the sole issuer of the US dollar. This is another way of expressing what is known as its “exorbitant privilege”.

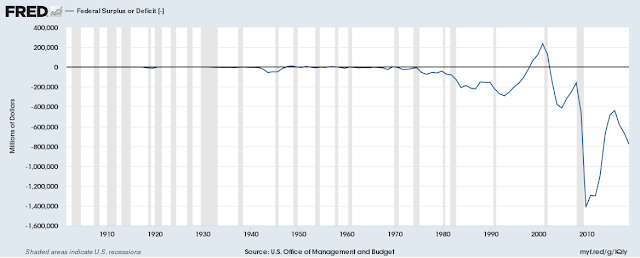

However, the dark side of this is that the US is obliged to run wide current account and fiscal deficits, because global demand for the dollar far exceeds US production. When it attempts to close these deficits, global trade and investment shrinks, causing market crashes and triggering recessions around the world. Sometimes, there is even a recession in the US itself. The US’s last attempt to run a fiscal surplus ended in the 2001 market crash and recession:

MMT adherents like to cite this as evidence that eliminating the government deficit in any country will result in a recession. But this is stretching things considerably. FRED shows us that even in the U.S., only one recession in the last century has been preceded by a government surplus.

Of course, many developed countries do in practice pay for imports in their own currencies. Governments, banks and corporations meet dollar funding requirements by borrowing in their own currency and swapping into dollars in the financial markets. This diminishes the need for dollar-denominated borrowing, either by government or the private sector. These countries therefore have a considerable degree of monetary sovereignty. But it is not absolute as it is in the United States. It crucially depends on the stability of their currencies and the creditworthiness of their borrowers, both of which are a matter of market confidence.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the government borrows dollars. Borrowing may be largely confined to the private sector, as (for example) it is in Turkey. But private sector FX borrowing is subject to the vagaries of capital markets. If the local currency depreciates significantly (see item 5 in the list), local banks and corporations can find themselves unable to service dollar debts, because dollars become far more expensive.

If banks stop lending cross-border, as they did in 2008, local banks and corporations can find themselves unable to refinance dollar debts. The world is littered with examples of countries that have had to run down public sector FX reserves to provide dollar liquidity to local banks and corporations after they are effectively shut out of global markets by local currency depreciation. If the public sector doesn’t have sufficient dollar reserves, it must borrow them, or face financial crisis, widespread debt defaults and economic recession. In an FX crisis, private sector external debt becomes public sector external debt.

Some say that since a currency-issuing government can always print more of its own currency, it can always buy dollars, however low the exchange rate falls. This is the assumption behind items 1 and 5 in the list. It is, unfortunately, a fallacy. Printing more dollars simply hastens the exchange rate collapse. After all, for you to buy dollars, someone has to be willing to buy your currency. And who in their right minds would buy a currency whose value in dollars was falling through the floor?

Printing money to fund an external deficit in a foreign currency always ends with the country shut out of markets and facing a painful choice between an IMF programme and debt default, possibly accompanied by hyperinflation. This has just happened to Argentina. Argentina, a country which issues its own currency, has free movement of capital and a floating exchange rate, does not have monetary sovereignty.

In general, the major reserve currency issuers tend to have more monetary sovereignty than other countries, because there is international demand for their currencies and their debt. The primary reserve currency issuer is the US, but the Eurozone (for which Germany is the primary safe asset issuer), the UK, Japan, Switzerland, Canada, and – now – China, all fall into this category.

However, there is a hierarchy even among reserve currency issuers. High on the list comes Japan, because its debt is held almost exclusively by its own citizens (and its central bank), and investors regard it as a “safe haven” in troubled times. But the ostensibly similar Switzerland has less monetary sovereignty than Japan, because it has extensive trade and financial ties to its much larger neighbour the Eurozone.

North Korea also has a high degree of monetary sovereignty, because it is autarkic. The price it pays for this is extreme poverty. Losing some degree of monetary sovereignty is surely a small price to pay for the openness to trade that brings prosperity.

Outside this somewhat exclusive club, monetary sovereignty becomes much diluted.

Few developing countries allow their currencies to float freely, and with reason. A floating exchange rate can be actively damaging to an economy if it is thinly traded and volatile, because the value of imports and exports varies so much: this is why the US dollar, and to a lesser extent the Euro, are so widely used in trade involving developing countries. For many developing countries, pegging to a stronger currency, or even adopting it outright, is the only way of creating sufficient stability for trade to develop.

Free movement of capital can also be extremely harmful to countries that don’t have well-developed capital markets and strong institutions. The damage done by hot money flows in and out of developing countries that have prematurely opened their capital accounts is well documented.

Small countries that have close trade and financial links with much larger ones do not have monetary sovereignty, even if their currencies are floating and they have free movement of capital. Perhaps the best example of this is Kazakhstan, which in 2014 was forced to float its currency after the Russian central bank floated the ruble. Kazakhstan’s close links with Russia made pursuing an independent monetary policy impossible.

For various reasons, therefore, most countries are not monetarily sovereign, even if they issue their own currencies and have floating exchange rates and open capital accounts. Sadly, if MMT’s policy recommendations rely on there being monetary sovereignty, it can never safely be used in more than a handful of countries. Monetary sovereignty is largely a myth.

Be the first to comment