Corporate Europe Observatory is a research and campaign group working to expose and challenge the privileged access and influence enjoyed by corporations and their lobby groups in EU policy making.

Since the British voted to leave the EU, corporate lobbyists have been hard at work to ensure any future EU-UK trade deal delivers maximum benefits and as little disruption to them as possible. Lobbyists from the financial sector – one of the key sectors to be negotiated – have been the most active of all, it seems. For them, the stakes are high. The financial sector based in the UK – often simply dubbed ‘the City of London’ – was instrumental in developing the EU rules on financial markets. Now their own access to that market is in peril, they have brought out the big lobbying guns.

Their lobbying offensive aims to influence a future trade deal between the two sides that promotes the interests of the financial sector, not just in London but in the EU27 member states as well. And their campaign represents a serious attack on regulation of financial markets in the public interest. They include plans that would lead to weakened regulations and specific threats to the public interest, such as ‘special courts’ that allow banks to sue governments if they adopt rules the financial sector finds unfair. If such proposals become reality they could, for instance, be used by corporations to prevent a small tax on financial transactions (FTT), or to stop attempts to make big banks more safe, and leave governments open to paying out huge fines awarded by such investment courts.

Just ten years after the financial crisis, which was fuelled by the lack of robust regulations, any weakening of rules, or the creation of mechanisms that privilege corporations, would be very far from the public interest. It is imperative, then, that negotiations between the EU and UK are made transparent, so that the public can see who is influencing the talks and what is being proposed.

Initial signs aren’t promising, however. While financial sector lobbyists have been granted enormous access to key officials, but freedom of information requests relating to their discussions are being obstructed by both the UK and EU. In part this mirrors the secrecy of previous trade negotiations, themselves the cause of much public concern. Incredibly, these trade talks are even less transparent than those of the notorious Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US.

Adding insult to injury, both sides argue that the secrecy is ‘necessary’ for their respective negotiators to secure a confidential space for reflection and in order to prepare their positions.

Financial services: privileged access to negotiators

Politicians and officials in both Brussels and the UK have engaged heavily with financial services lobbyists since the June 2016 Brexit referendum.

UK ministers in charge of Brexit, for example, held nearly 20 per cent of their meetings with finance lobbyists in the early stage of the discussions (56 meetings in total between October 2016 and June 2017). To put this into context, more meetings were held on finance with corporate lobbyists than with all of civil society, on any issue.

Lobby group TheCityUK, which has coordinated the drafting of some of the City’s proposals, has had over two dozen meetings to discuss Brexit in 18 months with UK ministers and senior officials in the Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU) and the Treasury alone. This access has been supplemented by over a dozen meetings, dinners, and receptions attended by ministers hosted by TheCityUK’s parent body, the City of London Corporation.

Individual financial sector firms have also enjoyed significant access to government. American investment bank Goldman Sachs, for instance, has had over a dozen solo meetings with British ministers and officials, including two private dinners with Chancellor Phillip Hammond.*

Despite the regular meetings between financial sector companies, their lobbyists, and Brexit decision-makers, we know little about how they are seeking to influence Brexit and any future trading relationship. While UK ministers and senior civil servants are required on a quarterly basis to publicly log meetings with outside interests, they rarely provide any useful information beyond this on what they are talking about. Many meetings are described simply as a “discussion on financial services”.

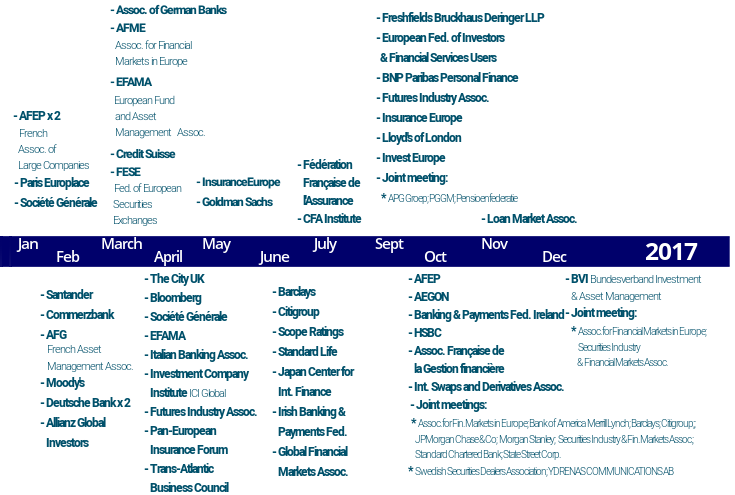

Meetings between EU negotiators and the finance lobby (2017)

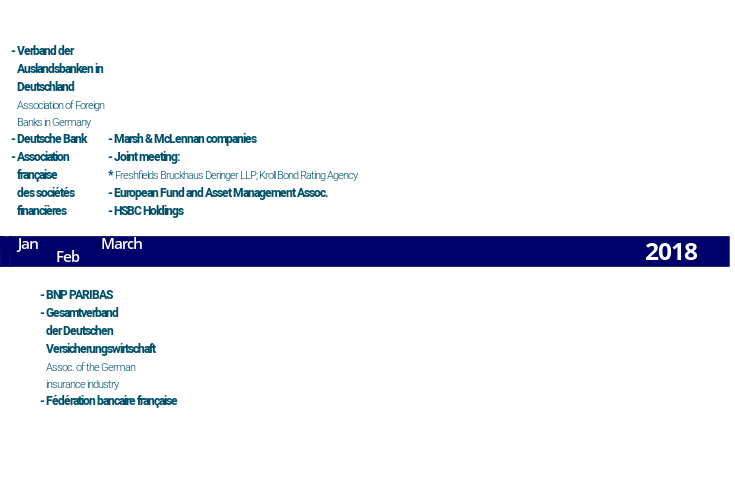

A similar picture emerges in the EU. From the beginning of 2017 till March 2018 the EU’s Brexit Taskforce had 67 meetings with financial corporations or lobby associations. This include three meetings with Deutsche Bank, and two with BNP Paribas and other big financial corporations on the continent. But the list is far from limited to corporations headquartered in the EU27. The list includes many names from the City of London such as Barclays and LLoyds, and US banks like Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs, not forgetting the many associations that count both EU27 corporations and UK corporations as members – not least TheCityUK and the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME).

Meetings between EU negotiators and the finance lobby (early 2018)

Top secret: Transparency and trade agreements

It seems ironic, then, that both sides of the negotiations have publicly committed to ensuring that discussions on future trade deals will be transparent, pledging that the public can be involved and comment on proposals before decisions are taken.

As UK trade Secretary Liam Fox put it last year, negotiators do not want to get into the same position as they did with the TTIP deal between the US and EU “where a huge amount of work is done only to find the public won’t accept it”. People, he said, now take a “much bigger interest in trade agreements” than previously. He promised that the public would be consulted.

The EU side sounded very promising too when, at the beginning, the Commission announced the negotiations would be conducted under “maximum transparency during the whole negotiation process”.

However, the reality is that both Westminster and Brussels are resisting formal access-to-documents requests to disclose even the most straightforward information on lobbying by the financial sector.

Even by the most basic measure, the UK’s Brexit departments have the worst transparency records in government. According to research by UnEarthed, DExEU responded fully to just 17 per cent of freedom of information requests in 2017 and the Department for International Trade (DIT) answered in full just 21 per cent of requests.

Behind these figures, as we show below, are decisions that go against not only the government’s requirement to disclose and the public’s right to know, but our ability to understand fully the deals that are being done behind the scenes with financial sector lobbyists.

‘The fishing expedition’

British departments are deploying all available exceptions to transparency rules, and stretching them beyond the limit. For example, Corporate Europe Observatory was forced into a year-long dispute with DExEU in the UK: first the authorities first questioned the motives behind the requests, then went on to a delaying tactic, and finished with a manoeuvre that ensured zero results.

In November 2017 Corporate Europe Observatory filed a simple request for information about meetings between DExEU officials and corporations such as HSBC, Barclays, BP, and Rolls Royce.** In response we received a letter from the department stating that they believed the request “may be a ‘fishing expedition’” for “information that is noteworthy or otherwise useful”. Moreover, the DExEU couldn’t see why they should be bothered to release anything. It would not be of interest to the public and it would require too much work, they argued.

This then led to a formal complaint, followed by negotiations on what kind of request would be acceptable in terms of workload. Corporate Europe Observatory then asked for minutes from thirty-nine meetings but was pushed by DExEU to bring it down to six, all of them with financial lobby groups.

Zero result after shrewd manoeuvre

Three months later we received a blanket refusal. No minutes existed in five of the six cases – the DExEU now claimed – and the minutes from the last meeting would not be handed over as it would “set an unwanted precedent and jeopardise the confidential environment necessary for optimal policy development”. The meeting in question was with a broad range of financial corporations under the umbrella of the lobby group TheCityUK and the meeting coincided with the launch of a key report issued by the group and the City of London Corporation through their joint body, the International Regulatory Strategy Group.

This could mean the meeting was important for policy-making. This seems to be confirmed by the letter in which the DExEU refuses access to information. There is a “strong public interest in policy making associated with our exit from the EU being of the highest quality and being fully informed by a consideration of all options”, the letter argued. And for that to happen there needs to be a confidentiality at meetings between negotiators and lobbyists, “frank and free from fear that it could be released to the wider public inappropriately, prior to the decisions being made”. It would even be likely to “prejudice the promotion or protection by the UK of its interests in the context of the withdrawal negotiations”. This begs the question what the UK’s interests are. Are the interests of the financial sector being viewed as part and parcel of the public interest? This view ignores the numerous history of scandals and controversies where the financial sector has acted with hugely negative consequences, for the general public in the UK and EU27 alike. Surely the public has the right to know, for example, about the possibility of this sector having access to ‘special courts’ that would allow them to sue against government policies they disliked?

Our work with other official UK bodies met with similar obfuscation. The office of the UK’s Permanent Representative to the EU rejected a straightforward request for a list of organisations with whom it has met since the referendum. Even appearing on a list of meetings could scare them off, they argued in a letter.

Inspired by secret lobby meetings

On the EU side, it sounded very promising when the Commission announced the negotiations would be conducted under “maximum transparency during the whole negotiation process”.viii In reality things are no better than on the UK side. An effort initiated in June 2017 to acquire documentation on meetings between EU negotiators and the financial sector has met the very same obstacles. While the Taskforce agreed to disclose lists of meetings with the financial sector covering the first year of its existence, which reveals extensive interaction with all major players, it would not reveal what these talks were about and refused to disclose the minutes. This is despite the fact that notes were certainly taken. Negotiators were there to be inspired: “During all of these meetings the Commission’s representatives were in listening mode and took note… of the information that was shared by the stakeholders. They also include the opinions and evidence raised by the third parties, which represents know-how and commercial data of the organisations.”

A collection of courtesies

Corporate Europe Observatory wanted to known if such “opinions” from financial sector lobbyists included a push for controversial proposals like special courts for investors? A new freedom of information request in April 2018 was met with a whole new level of opacity. While initially it appeared that new ground was broken, with 186 pages handed over, they did not provide any meaningful transparency. In the main they are exchanges of courtesies in connection with the setup of meetings, a collection of “Thank you in advance”, “I look forward to hearing from you”, etc. Any real content has been redacted or removed.

A complaint and a narrowing down of the request didn’t help. In terms of access to minutes this gave practically no result. Besides disclosing the name of a chief executive from an exchange ahead of a meeting with the Commission (Ken Bentsen of SIFMA), the new information included no more than a few further polite remarks.

The reason they gave for secrecy was, besides some standard phrases on protection of “commercial secrets”, that “public disclosure would… risk upsetting the negotiations” and for that the Commission “needs to preserve a ‘safe space’ for confidential preliminary exchanges”.

Less ‘disruption’ than ever

What is clear is that there is no willingness on the part of either Brussels or the UK to share the content of exchanges between decision-makers and the financial sector. On the EU side this represents a major setback on transparency.

While the negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the US and the EU were not transparent, at least reports of minutes between negotiators and the EU were released on request, albeit always after a lengthy tug-of-war and in a harshly edited fashion. Back then edits were in the main about negotiators keeping their cards close to their chest, not about what positions lobbyists were pushing at meetings. This includes meetings with the financial sector. During the TTIP debate a single request could lead to the disclosure of not only dozens of minutes but meeting documents as well, including position papers from different branches of industry.

In contrast, in these early stages of talks over a future EU/UK trading relationship, financial sector lobbyists will have been helping to shape positions and push their agendas with officials on both sides, but with no public scrutiny. While transparency rules do allow for exemption of information that would undermine international relations, they do not provide for the kind of blanket rejections we see here.

Closed discussions on controversial proposals

Negotiators on both sides share a lack of appetite for transparency, primarily based on a desire to avoid “disrupting” internal decision-making in preparation for trade negotiations.

That begs the question what kind of disruptions concern them? If they were worries about each of the sides plotting with ‘their own’ financial sector, it would be a case of banal mercantilism. But in modern day finance the space for that is quite limited. Groups such as TheCityUK actually claim to represent financial corporations on both sides whereas others, such as Goldman Sachs, can hardly be regarded as a player for either side. The reality is, there is cooperation between financial corporations on both sides to secure a deal they would regard as favourable for the sector as a whole.

The reluctance of negotiators to open up, then, appears to be more about avoiding any kind of public debate on how the two sides find a deal over the crucial financial sector. The stakes are potentially very high. In recent years, the financial sector has lobbied for proposals that have met stiff public opposition, including the introduction of special private courts to settle disagreements between a state and investors. An Investment Dispute Settlement System (ISDS) could in future be used to prevent states from adopting rules on finance that are in the public interest, or lead to governments facing massive fines. Rules such as a Financial Transactions Tax (FTT), which the City has lobbied fiercely against for years. Proposals currently being put forward by lobby group UK Finance, for example, whose members include megabanks BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank, Barclays, and Lloyds,xiv if adopted, could lead to an FTT being fought in special courts and perhaps defeated.

Urgent action needed

On both sides, negotiators are fighting tooth and nail to avoid disclosure of anything that could put the real stakes on display. This much is clear, as far as lobbying by the financial sector is concerned. Moreover judging by the exchanges with the authorities, the arguments they use indicate an intention to defend secrecy at the negotiations more broadly.

It seems that if you ask the negotiators, the EU Task Force headed by Michel Barnier, and the Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU) headed by Dominic Raab, they would both prefer a lot of “privacy” around their interaction with lobbyists.

Should a trade agreement be negotiated under the present conditions, it would help the two sides hide the fate of controversial proposals and perhaps present the1m only when a final deal has been reached. At that point in time renegotiation will most likely be out of the question and that will put politicians who feel uncomfortable with the menu served with an unpleasant choice: either they reject it and cause a major political crisis or they swallow it. Such a scenario is unreasonable and undemocratic.

This article was written as part of an ongoing collaborative research on Brexit and lobbying involving CEO, SpinWatch, LobbyControl and Observatoire des multinationales, within the ENCO (European Network of Corporate Observatories) network. A longer report will be out in a few weeks.

* From access-to-documents requests filed by Tamasin Cave (SpinWatch).

** HSBC, Rolls Royce, PWC, Barclays, CBI, BP, KPMG, Standard Life, GSK, Prudential, BT, Caterpillar and Mitsubishi.

Be the first to comment