Some of the candidates put forward to become the new European Commissioners are of concern due to potential conflicts of interest – from share ownership in fossil fuels and finance to overly close relationships with business – and corruption probes, while MEPs complain of a lack of a robust transparency process to properly scrutinise the interests of the Commissioners-designate.

Corporate Europe Observatory is a research and campaign group working to expose and challenge the privileged access and influence enjoyed by corporations and their lobby groups in EU policy making.

Cross-posted from Corporate Europe Observatory

UPDATE: On26 September MEPs in the legal affairs committee agreed to block Commissioners-designate Laszlo Trocsanyi, from Hungary, and Rovana Plumb, from Romania, from passing on to the hearings stage. MEPs agreed with our assessment of Trocsanyi’s murky relationship with his law firm. This is the first time that MEPs have the power to block individual candidates but the next steps are unclear.

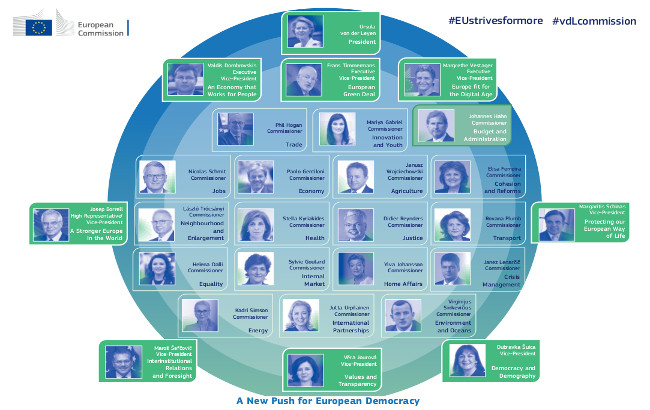

Many of the 26 commissioner candidates put forward by national governments and agreed to by President-elect Von der Leyen have caused concern. At least three are currently the focus of open investigations from police or anti-fraud bodies for mis-use of public funds and corruption, and another has been shielded from investigations.

As MEPs prepare to vet the proposed Commission new problems arise: potential conflicts of interests with the commissioners’ investments and professional backgrounds. Concerns range from unclear relationships with law firms, to shares in the financial and fossil fuels industry.

Trócsányi’s mysterious relationship with law firm

The most controversial name in the list of potential new Commissioners is Lazslo Trócsányi. His role as Viktor Orbán’s Justice Minister, in which he shepherded the attacks on Hungary’s civil society and rule of law, haunt his EU ambitions. But his involvement in a Hungarian law firm should also be probed by MEPs in the hearings starting next week.

Trócsányi is set to take over the Neighbourhood and Enlargement portfolio, which would put him directly in charge of guaranteeing that the rule of law and democratic values are respected in countries that want to join the European Union, especially in the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe. However, his record in the Hungarian Government saw him leading a long list of attacks on civic and human rights: threats to the independence of the judiciary; limiting the freedom of expression and gathering of NGOs; abhorrent treatment of asylum seekers, migrants, and homeless people; attacks on academia; and the inability to tackle corruption.

As Minister of Justice he also set up an administrative court that if approved will have the sole responsibility for issues such as electoral law, corruption, right to protest, and freedom of information. This new body will be made up of judges selected by the Minister of Justice directly, risking its independence and further eroding the rule of law in Hungary. Sidenote

Trócsányi’s role in attacks on civic rights alone should had been enough to make President-elect Von Der Leyen reject his nomination. But instead, she put him in charge of overseeing whether ascension countries are implementing reforms to defend the rule of law and tackle corruption. Orbán has been seeking this portfolio since 2014, supposedly due to the country’s interests in the Western Balkans where his Government is investing heavily to expand business and political networks.

Yet Trócsányi’s candidacy has another cause for concern: his relationship with the law firm he co-founded, Nagy és Trócsányi. The former Minister set up this law practice in 1991 with partners focusing on “international commercial and business law” advertising a wide range of services including banking and financial, mergers and acquisitions, international arbitration, and tax. The firm works in Hungary and in the United States and known clients include BNP Paribas, OTP Bank, Uber, and the Hungarian Government.

Trócsányi’s relationship with the law firm has been thoroughly criticized in Hungary since he became Minister of Justice in 2014. As Minister, Trócsányi handled files that were directly related to his own company’s interests, including speedier arbitration rights for investors, and the company was allegedly awarded numerous governmental contracts while he was in the role.

The Minister was seemingly unable to separate himself from his previous company. Trócsányi even hired as special adviser one of the company’s Chairs, Tibor Bodgán, which allowed his former colleague to participate in government meetings. Before Trócsányi left the Ministry, Bodgán was even put in charge of ensuring that the administrative court system was operational.

The real nature of the relationship between the former Minister of Justice and the law firm is murky. When confronted about it in 2015 Trócsányi explained his participation in the company had been “suspended” since 2007, but Hungarian media reported that throughout most of his time as Minister, Trócsányi kept a financial stake in the company.

This month Trócsányi told Der Spiegel that “he has not been financially involved with the firm for over a year”. But this is not enough to assure that there is no risk to his independence. The Commissioner-designate should clarify what he did with the shares (whether he sold them or put them in a trust), how the suspension is defined, and if he plans on returning to the company after his time at the European Commission.

All of these questions need to be resolved if he is to take on a Commission role.

Dirty shares: Commissioners-designate invest in fossil fuel and finance industry

The vetting by the Legal Affairs Committee has also unveiled that several commissioners hold shares in companies – including in the finance and fossil fuel industry – that are actively trying to influence EU policy-making.

The Spanish nominee, Josep Borrell, is particularly concerning as he allegedly holds shares in chemical giant Bayer (which recently bought Monsanto), financial group BBVA and, finally, energy company Iberdrola. All of these are registered EU lobbyists.

Members of the European Parliament’s legal affairs committee asked Borrell if he had considered selling these shares to resolve potential conflicts of interest. Surprisingly, he had not as to him “these shares represent a small amount of my financial assets” and he considers their sectors of activity as unrelated to his portfolio. However, a quick look at his predecessors list of lobby meetings reveals that she and her cabinet often dealt with energy issues, trade deals and business’ actions in foreign markets.

In a similar position is Austrian Commissioner Johannes Hahn who has been a member of the Commission since 2010 and is now billed to take over the Budget and Administration portfolio. His 2018 declaration of financial interests also shows an array of investments in fossil fuel and financial companies.

Hahn declared shares in OMV AG, an Austrian oil and gas company. Investing in fossil fuels is already problematic in the light of the Commission’s Green agenda. As a future Commissioner for Budget he might very well become responsible for decisions involving fossil fuels which make his investments in an oil and gas company particularly troubling.

To make matters worse OMV is an active lobbyist that has had at least 13 meetings with the highest level of the Commission since 2014, mostly to discuss gas infrastructure and energy security. The Austrian company is also a shareholder of the controversial gas pipeline project NordStream II, whose representatives at EU level have lobbied Hahn’s team directly while he was a European Neighbourhood Policy & Enlargement Negotiations.

The Commissioner’s investments include Verbund AG, an Austrian electricity provider that is also an active EU lobbyist, that even had a meeting with Hahn’s own cabinet in 2014 to discuss ‘Energy issues in the EU’. Hahn’s shares are not restricted to the energy sector. The Commissioner has also expanded into financial interests with shares in the Erste Group, a financial services company whose EU lobby footprint shows has met with Hahn’s predecessor as Budget Commissioner, Oettinger; and finally the Raffeisen Bank International AG.

Investing in companies that have an active interest in shaping EU policy creates a clear conflict of interest regardless of the portfolio. Commissioners’ responsibilities include participating in College discussions in all areas of EU politics. MEPs must make selling these shares a pre-condition to become a Commissioner.

According to media reports, both Portuguese Commissioner-designate Elisa Ferreira and Cypriot commissioner-designate Stella Kyriakides have sold their shares (in Portuguese supermarket and shopping center chain, SONAE, and coffee company, Starbucks, respectively). Others should be able to do the same.

Goulard and the think tanks

The French Commissioner-designate Sylvie Goulard is another highly controversial candidate. On the very day her name was officially confirmed as the Commission’s pick to take over the Internal Market portfolio, Goulard spent hours with the French police giving testimony for an open investigation into her role in the mis-use of EU funds.

She was forced to resign in 2016 from the post of Minister of Defence in Macron’s Government when it was revealed that when she was an MEP she used EU funds to pay for a parliamentary assistant, who in fact was working for her party back in France. Goulard has since returned €45,000 to the European Parliament and representatives of the institution declared the case closed. However the investigation continues in French courts and, of course, at the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF).

Goulard has also been under fire from French media over her relationship with US think-tank the Berggruen Institute, which was set up by billionaire financial investor Nicolas Berggruen. As an MEP she declared working at the think-tank as a special adviser from 2013 to 2015. The declaration of financial interest that Goulard submitted to the French High Authority for Transparency in Public Life when she became a Minister clarifies she received the substantial sums of €36,047 euros in 2013 and €13,000 euros in 2014 from the think-tank. La Liberation tried to discover what she did for the Berggruen Institute to merit such payment but only uncovered evidence of a minimal amount of co-editing of policy notes and participation in very few meetings. This makes the amount she was paid seem even more substantial.

This was not the only position she held during her European Parliament mandate. As an MEP Goulard was a member of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, key for the regulatory discussions that took place following the financial crisis. During this period of time Goulard also declared being a member of the steering committee of the European Parliamentary Financial Services Forum (EPFS), a non-official group that brings together MEPs from different political groups and financial industry actors. The EPFS is run by lobby firm Kreab and funded by fees paid for by the industry members such as the European Banking Federation, the Association for Financial Markets in Europe, Blackrock, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, among many others..

Goulard also co-founded United Europe, a not-for-profit pro-European think-tank with the motto “United Europe: Competitive and Diverse” that organises pro-European speeches, conferences, research projects, and seminars. The think-tank is also funded by membership fees and donations and its members include 31 corporations such as Airbus, British American Tobacco, and Iberdrola. She left United Europe when she took up a job at the Bank of France

Showing some good transparency practice, Goulard did list the trips she took as an MEP paid for by externals which shows that she was a regular at financial lobby events (including Eurofi). One stands out, a trip paid for by Barclays to meet their investors.

Under the new Commission structure Goulard will become responsible for the internal market Sidenote , including the digital and defence market, and as such we can expect her to be the focus of intense business lobbying. It is therefore particularly important to ensure that any candidate holding this mandate should not have any potential conflicts of interest. During the hearings MEPs should also probe into how Goulard plans on interacting with corporate lobbyists, and whether she is prepared to ensure they don’t have privileged access and influence over the Commission departments she will oversee.

Family interests

One aspect in the assessment of candidates’ probity relates to the interests of family members, a crucial question for example during the vetting of Commissioner Cañete in 2014. This time, there are questions to be asked of Swedish nominee Ylva Johansson, whose partner Erik Åsbrink is a former Finance Minister who now runs a business consultancy, Åsbrink & Far AB, working “in Sweden and internationally with a focus on finance, consultancy, lectures, authoring of books and articles, and related activities. The company shall also conduct securities management and related operations.” Media reports from 2011 add that he is an adviser to Goldman Sachs on “business development opportunities in Sweden and the Nordic region”.

A thorough assessment should determine whether his company provides advice to companies on EU policy and whether there is any overlap with Johansson’s future work. Unfortunately it seems that MEPs in the Legal Affairs Committee decided against asking any of these questions and Johansson has been cleared.

Incomplete declarations and corruption allegations

The lack of information about things like shares owned and similar connections with the private sector, seems to be a constant in the declarations. According to the EUObserver, four of the declarations received were almost empty and others seemed to contradict previous declarations or other sources of information. This indicates the declarations haven’t been taken seriously enough by the Commissioners-designate. For example Rovana Plumb was asked to clarify why her declaration differs from the one she had made to the Romanian authorities. MEPs are particularly worried that Plumb did not mention the € 1 million loan that she has taken from an undisclosed individual. She will surely still have questions to answer regarding her involvement in the controversial sale of public land that benefited the family of her party’s former leader. The investigation into Plumb was never concluded as the Romanian Parliament protected her immunity.

Two other Commissioner-designates are the subjects of ongoing investigations. These are the Polish candidate Janusz Wojciechowski, who is also under investigation by OLAF for alleged irregularities in his travel expenses; and the Belgian candidate, Didier Reynders, who is now the subject of an investigation into allegations of bribery during his time in government.

Flawed process

The responsibility for ensuring a balanced, competent, and independent commission is shared between the three EU institutions.

National governments put forward the names they wish to see become a part of the college. The concerns surrounding these names show once again that some national governments do not take these EU processes seriously enough. Of course, it is also an indication that President-elect Von Der Leyen should have been stricter and not accepted candidates that are the subject of open investigations or have potential conflicts of interest.

It is now MEPs’ turn to assess the candidates. It is heartening to see the Legal Affairs Committee demanding clarifications from nominees, an improvement from what happened in 2014, but the process is still flawed. According to MEPs themselves, they did not have enough time to thoroughly examine the declarations, and the guidelines of what they should be scrutinising are disputed. So much so, that there are fears this process will end up as a mere rubber-stamping exercise.

It is clear that this scrutiny is a sensitive process that requires time, resources, and experience. While it is positive that there is political oversight from the European Parliament, the obstacles that MEPs currently face in assessing the candidates only highlight the need for an independent ethics body that would remain distant from the political agreements and horse-trading, and would be equipped with the resources to properly vet the new Commissioners.

Be the first to comment