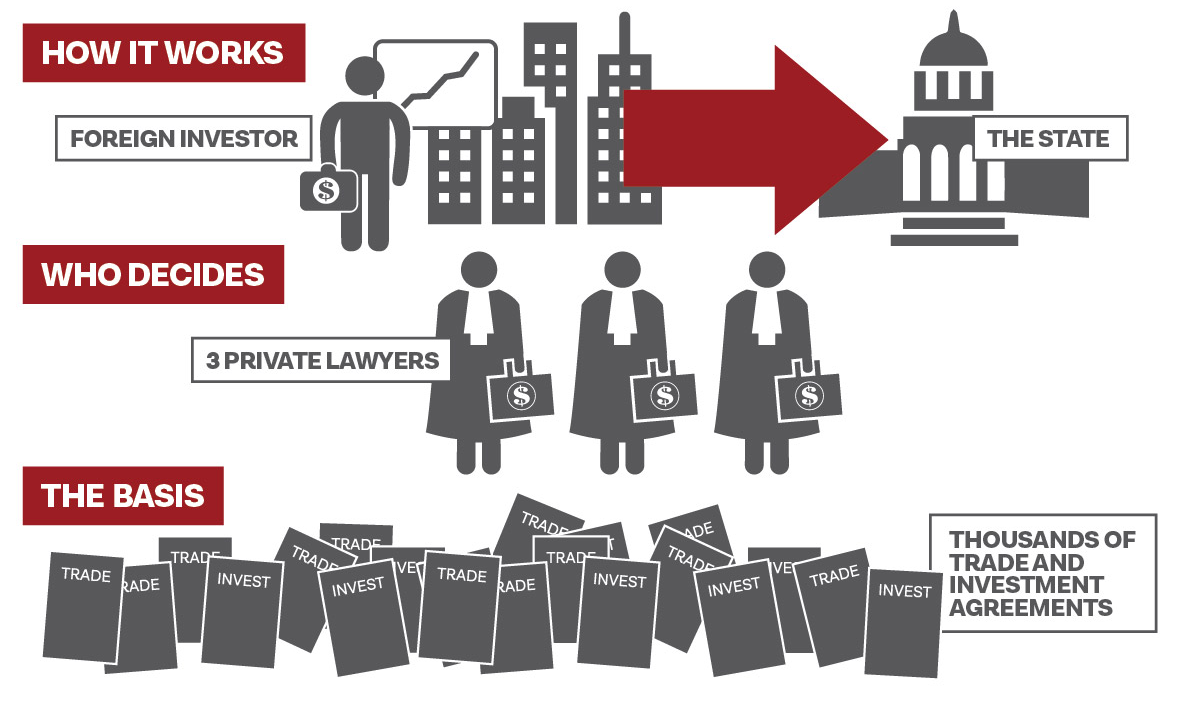

New research published today reveals the devastating consequences of the controversial Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system. A common ingredient in international trade and investment agreements, ISDS creates a parallel justice system that rolls out the red carpet for corporations to sue states when they act in the public interest.

Red carpet courts: 10 stories of how the rich and powerful hijacked justice, by Corporate Europe Observatory, the Transnational Institute and Friends of the Earth Europe/International, gathers 10 recent cases from around the world that show why ISDS and its copy-paste rebranding pushed by the EU have no place in any international agreement. The research comes one day before EU member states’ likely approval of a new EU-Vietnam investment agreement, which includes ISDS-style courts (25 June).

A full copy of the report is available here: http://10isdsstories.org/

“If you wanted to convince the public that international trade agreements are a way to let multinational companies get rich at the expense of ordinary people, this is what you would do: give foreign firms a special right to apply to a secretive tribunal of highly paid corporate lawyers for compensation whenever a government passes a law to, say, discourage smoking, protect the environment or prevent a nuclear catastrophe. Yet that is precisely what thousands of trade and investment treaties over the past half century have done, through a process known as ‘investor-state dispute settlement,’ or ISDS.”

This is how, in autumn 2014, The Economist introduced its readers to a once unknown element in international trade and investment agreements. The business magazine referred to ISDS as “a special privilege that many multinationals have abused”1 and mentioned two infamous examples: Swedish energy giant Vattenfall suing Germany for €6.1 billion2 in damages because the country phased out nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster; and tobacco company Philip Morris suing Uruguay and Australia over government health warnings on cigarette packs and other measures to reduce smoking.

The legal basis for these investor-state dispute settlements – known under the acronym ISDS – is over 2,650 international trade and investment agreements in force between states worldwide.4 These agreements give sweeping powers to foreign investors, including the peculiar privilege to directly file lawsuits against states at international arbitration tribunals. Companies can claim compensation for actions by host governments that have allegedly damaged their investment, either directly through expropriation, for example, or indirectly through virtually any kind of regulation. ‘Investment’ is interpreted so broadly that mere shareholders and rich individuals can sue, and corporations can claim not just for the money invested, but for future anticipated earnings as well.

Red Carpet Courts

ISDS claims are usually decided by a tribunal of three private lawyers – the arbitrators – who are chosen by the litigating investor and the state. Unlike judges, these for-profit private sector arbitrators do not have a flat salary paid for by the state, but are in fact paid per case. At the most frequently used tribunal, the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), arbitrators make US$3,000 a day.5 In a one-sided system where only the investors can bring claims, this clearly creates a strong incentive to side with companies rather than states – because investor-friendly rulings pave the way for more lawsuits and more income in the future.

THE CHRONOLOGY OF AN INVESTMENT ARBITRATION

The process starts when a foreign investor sends a notice of arbitration to a state. Unlike in other areas of international law, the claimant does not have to go through local courts first. Both, the investor and the state will be assisted by lawyers (counsel) during the proceedings.

The investor and the state jointly select the arbitration tribunal. Usually each party picks one arbitrator and both jointly appoint a third to serve as president. The arbitrators are private, for-profit lawyers, not judges, who are paid by the case.

Proceedings last years and mostly take place behind closed doors, with scant or no information at all released to the public, sometimes not even the fact that a case is happening.

The arbitrators ultimately determine if the state violated the ECT’s investor rights and the size of the remedy. They also allocate the legal costs of the proceedings. Opportunities to challenge the rulings are extremely limited – even if they appear clearly wrong.

States have to comply with arbitral awards. If they resist, the award can be enforced by actual courts almost anywhere in the world by seizing the state’s property elsewhere (for example, by freezing bank accounts or confiscating state aircraft or ships).

Weapons of legal destruction

Since the late 1990s, the number of lawsuits taken by investors against states has surged – and so has the amount of money involved (see box 1 below). The last two decades have also seen multibillion dollar claims alleging damage to corporate profits as a result of legislation and government measures in the public interest. Developed and developing countries on every continent have been challenged by companies for trying to introduce regulations to promote: financial stability measures, bans on toxic chemicals, mining restrictions, anti-discrimination policies, environmental protection laws and more. A lawyer who has defended many governments in these lawsuits has hence called investment treaties “weapons of legal destruction”.6

Sometimes, just the threat of an expensive dispute has been enough to freeze or delay government action, with policymakers realising that the cost of public interest regulation is too much for the state to bear. Five years after the foreign investor rights in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, a former Canadian government official told a journalist: “I’ve seen the letters from the New York and DC law firms coming up to the Canadian government on virtually every new environmental regulation and proposition in the last five years. They involved dry-cleaning chemicals, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, patent law. Virtually all of the new initiatives were targeted and most of them never saw the light of day”8 . (see cases against Colombia and France for examples of this ‘regulatory chill’ effect).

Box 1: Striking figures from the world of ISDS9

- Investor-state legal cases have mushroomed in the last two decades, from a total of six known treaty cases in 1995 to a record high of over 70 new claims filed annually since 2015.

- Globally, 942 disputes against 117 countries have been recorded throughout the history of ISDS as of 1 January 2019, but due to the lack of complete and transparent publicly available information the actual figure could be much higher.

- In the 70 per cent of the known cases for which this information is available, investors have sued governments for the total sum of US$623 billion. This is equivalent to 90 per cent of all Foreign Direct Investment flows to all developing countries in 2018.10

- Investors have triumphed in 61 per cent of investor-state cases where there has been a decision on the merits of the case, whereas states have ‘won’ only 39 per cent of the time (even through states can’t ever win through ISDS, only not lose and thus succeed in avoiding having to pay out damages).

- Nearly a quarter of ISDS cases end in settlement, most likely involving payments by governments or changes in laws and regulations to appease disgruntled investors, often in partial or total secrecy, meaning citizens don’t know where their public money went, or why a policy was changed.

- The total amount of money which states have thus far been ordered or agreed to pay in disclosed ISDS rulings and settlements is US$88 billion – a startlingly large figure, which is equivalent to all Foreign Direct Investment to Australia, Japan and other developed economies outside of Europe and North America in 2018.11

- Award amounts may reach up to 10 figure sums. The highest known damages awarded to date, US$50 billion, were ordered against Russia, to the former majority owners of oil and gas company Yukos.

- The main financial beneficiaries of ISDS have been large corporations and rich individuals: 94.5 per cent of the known awards went to companies with annual revenue of at least US$1 billion or to individuals with over US$100 million in net wealth.12

- Legal costs for disputes average around US$4.9 million for states and US$6 million for investors, but can be much higher.13 For the Yukos claims, total legal costs rose above US$124 million14 and the arbitrators took US$7.4 million for themselves.15 As legal costs are not always awarded to the winning party, states can end up footing the bill even if they don’t lose.

Investment arbitration in dire straits: a global storm of opposition

The growing number of corporate lawsuits has raised a global storm of opposition to ISDS, from across the political spectrum. Around the world public interest groups, trade unions, community groups and academics have repeatedly proclaimed opposition to ISDS and urged governments to exit from the regime.16 Proponents of free markets and trade, such as the right wing US think tank Cato Institute, too, have joined the opponents’ camp, arguing that “the ISDS approach of providing… protections only for foreign investors… is akin to saying in a domestic constitution that the only rights we will protect are those of wealthy property owners.”17 Judges have also started to raise similar concerns, stating that “the creation of special courts for certain groups of litigants is the wrong way forward.”18

Some countries, too, have realised that the promised benefits of investment arbitration have not materialised (see box 2 below) and are trying to escape from the system. South Africa, Indonesia, India and many other countries have terminated some of their bilateral investment treaties (BITs) in recent years.19 In 2019, EU member states announced that they would terminate all their bilateral treaties with each other – roughly 200 agreements.20 Italy has also left the Energy Charter Treaty, a large ISDS deal for the energy sector.21

Box 2: Busting the myth that investment agreements and ISDS bring investment

ISDS supporters argue that “investors are… more likely to make a cross-border investment… where the host state provides some form of investment protection”.23 They claim that the right to sue states in “neutral” dispute resolution fora outside of domestic courts has a particularly positive effect – because it serves as a “check” to the alleged “arbitrary or unlimited use of government power”, increasing “the desirability of a State as a potential inward investment destination”.24

This may sound plausible to some, but there is one major problem with this argument: there is no clear evidence that investment agreements actually bring investment. While some econometric studies find that they attract some investors, others find no effect at all – or even a negative one. Qualitative research suggests that for the vast majority of investors, investment treaties are not a decisive factor when they go abroad.25

Governments have also begun to realise that the promise of foreign direct investment (FDI) has not been fulfilled. After South Africa cancelled some of its investment treaties, an official explained: “South Africa does not receive significant inflows of FDI from many partners with whom we have BITs, and at the same time, continues to receive investment from jurisdictions with which we have no BITs. In short, BITs have not been decisive in attracting investment to South Africa.”26 This has also been the experience elsewhere; Brazil, for example, receives the largest amount of FDI in Latin America27 – despite never having ratified a treaty allowing for ISDS. In Indonesia, FDI from the Netherlands increased by 19.2 per cent in 2015 – even though the country had terminated its investment treaties with the Netherlands and several other countries the year before.28

More importantly it is now widely acknowledged that while FDI may contribute to development, its negative impacts can be substantial, while the benefits of FDI are far from automatic. Regulation is needed to generate positive effects locally, such as decent jobs, generation of tax revenues, or technology transfer – and to avoid the risks that FDI can pose to the environment, local communities etc. Investment agreements are not only agnostic on these crucial development issues, protecting investments irrespective of their nature and impact, but their “pro-investor imbalance can (also) constrain the ability of governments to regulate in the public interest”, as an official of the Government of South Africa put it.29

ISDS at a crossroads: global expansion and continuing public resistance

Meanwhile, a number of international agreements currently under negotiation or being ratified, threaten to massively expand the ISDS regime, subjecting states to even more liability. These include the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA, bringing together 44 African economies), the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP, under negotiation by 16 Asia-Pacific countries), the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, signed by 11 states from the Pacific, Chile, Mexico, and Canada) and several bilateral deals, including agreements between the EU and China, Canada, Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Mexico.30 The EU also plans to scale up – and re-legitimise – ISDS via a permanent global court for investor-state disputes.31

However, resistance to the red carpet legal treatment of companies continues to build. In a significant moment, aiming to prevent the EU from expanding and locking in ISDS – and to build public pressure for a global system that can punish multinationals for their crimes – more than 200 civil society organisations from across Europe came together in January 2019. Within just two months, over half a million Europeans had supported their call to end corporate impunity.33 In the run up to the European Parliament elections in spring 2019, hundreds of MEP candidates also pledged to vote against all forms of ISDS and for binding corporate accountability rules. This gives hope to a whole generation of activists. As the UK-based campaign groups put it: “Campaigners all across Europe are gearing up to create an unstoppable momentum for change in our own countries. We’re at a tipping point, and if enough of us come together, we could bring ISDS down altogether.”34

SOME COUNTRIES WHICH HAVE TERMINATED INVESTMENT AGREEMENTS35

Be the first to comment