A remarkable revelation: the London police admit they refused to reveal the real number of dead from the Grenfell fire because they believed to do so could lead to Muslims’ rioting

Cross-posted from the LSE Politics blog.

In the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire, the question of the true death toll was a source of deep distress and anger locally. It was raised and questioned repeatedly by people affected, in public meetings, in the media, and in local conversations trying to make sense of what had happened. There were rumours of a cover-up, claims that hundreds had died, and suspicions that something was being hidden from the public. The death toll was simultaneously central to the significance of the disaster and unknown or ambiguous for months. People wanted the truth. They did not know the true death toll, but they did know they had not been given it.

Now, five years later, we learn, through the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, of a Community Impact Assessment produced by the Metropolitan Police, which explains their reticence with information about deaths. The assessment claimed that disclosing the death toll risked igniting tensions and provoking disorder by Muslims. Module 4 of the Public Inquiry addressed the initial response by authorities in the aftermath of the fire. On 27 June 2022, Alison Munroe QC, in her closing statement for Module 4, quoted from the Met’s Community Impact Assessment, produced 5 days after the fire, which stated:

“There is an expectation that the death toll from the fire could rise substantially. And with the cause unknown, any subsequent disclosure would have the impact of community tensions, especially when the majority of those affected are believed to be coming from a Muslim cultural background combined with the incident occurring during the holy month of Ramadan.”

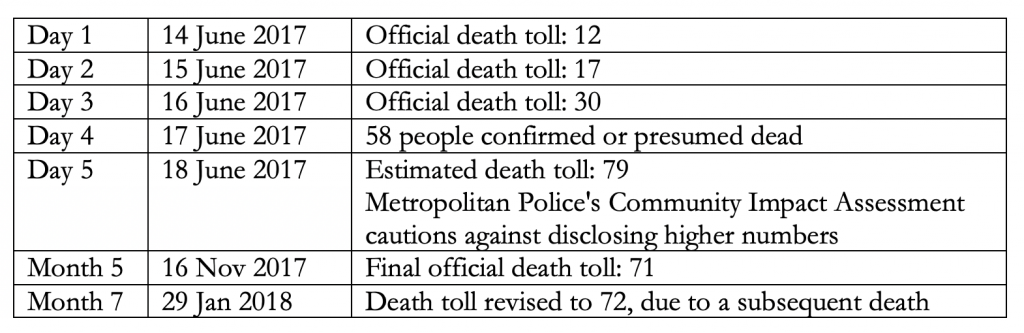

The evolving death toll and its impact

As people actively involved in contributing to and documenting the community response after the fire, we had been puzzled and infuriated at the time, over the police’s caginess about the death toll, when the absence of information was so clearly causing distress, anger, and distrust. This new information that it was a conscious choice to be economical with the truth is devastating. To understand the timing and nature of community knowledge about the death toll, we have returned to our documentation to present the sequence of death toll announcements, and the corresponding experience in the community. Here is the sequence of figures released:

In the early days, the disconnect between what people had seen and experienced of the fire, and the official death toll was a cause of great distress and suspicion. Local people knew that more than 17 or 30 people had died. They had seen the inferno. Some people had helped compile lists of those missing, based on local knowledge of who lived in which flat, because information was not forthcoming through any other route. These local death tolls contradicted the official estimates, exacerbating suspicion. If the police’s ‘Community Impact Assessment’ had understood communities, it would have appreciated that in communities, people talk to each other, share knowledge, and share concerns. Some people speculated loudly that the numbers of dead were in the hundreds, not the tens, accusing authorities of a cover-up to minimise the disaster. On social media, the idea that numbers were far higher than the official toll was seized on by hateful xenophobic propagandists to claim that the Tower had housed numerous ‘illegal’ immigrants. These claims continued to circulate for years, causing deep further hurt to the community.

Ultimately, the number released on day five (79) turned out to be very close to the final death toll of 72, but by this stage, local people had little reason to believe this number more than the others. The communication of this estimated death toll was accompanied by emphasis that it was provisional, and the uncertainty continued to cause much discussion and distress. At the first community public meeting between authorities in charge of the response and community members, on 5th July 2017, members of the audience raised questions about the true death toll. On 7th July, Siân Berry, Green Party member of the London Assembly, requested the Mayor to produce a Greater London Authority interim estimate of the numbers of lives lost, to address the genuine pain being caused by the uncertainty. Uncertainty about the true toll continued until finally on 16 November 2017, five months after the fire, when police announced a final death toll of 71, which largely gained acceptance, bringing a limited sense of closure on the particular question of the toll. Sadly that number later increased to 72, upon the subsequent death of a resident who had escaped the fire but never left hospital.

Why the reticence about the death toll?

During those early days and months, the police stated that they could not confirm a death until they had physical confirmation of identification. No doubt, the recovery and identification process was a painstaking and difficult task. Respecting the privacy of the deceased and bereaved was essential. But insisting on such strict adherence to official procedures felt completely disproportionate to the problem at hand. The community was hungry for information and rather than concealing the truth, clarity about what was known, what was not known, and best estimates would have gone a long way to giving the community confidence. Instead, they had to live with temporary, incomplete knowledge, allowing rumours of far higher numbers, and suspicions of being manipulated to circulate and gain credence.

Now it is revealed that it was a conscious choice on the part of the Metropolitan Police to withhold information, apparently based on an Islamophobic claim that if higher numbers were revealed, disorder may ensue. Not only is this an inhumane position, it is also baseless. Muslim, Christian, Sikh and non-religious communities and centres pulled together to focus on the urgent task of providing support to survivors, bereaved families, and local residents. In the chaotic aftermath, emerging and established community leaders worked actively to curtail agitation or disorder. Multi-faith vigils were held daily. The very first silent walk took place on 19 June, setting the tone of dignity that was to characterise the response of the affected communities.

For those who had any connection with the local Muslim community, the idea that Muslims were prone to rioting was ludicrous. Local hip-hop artist, Lowkey, has suggested that the notable absence of riots post-Grenfell is due to the fact that the majority who died were Muslims (cited in Monique Charles’ contribution to the book After Grenfell, 2019). He argues that the strength of Islamophobia in Britain means that Muslims understand the risks of being labelled as violent, and thus associated with terror, incivility, un-Britishness, deserving of the most severe punishment. The police assessment of a propensity for disorder was the opposite of reality, showing the poor ‘intelligence’ on which their Community Impact Assessment stood.

Disasters, deception, and distrust

Everyone talks about distrust being a key feature of the recovery period post-Grenfell. Among those seeking to understand why recovery has been so difficult, the problem of ‘distrust’ is mentioned with some sympathy towards the authorities – the police, local council, anybody connected with government – charged with delivering the response and recovery. Certainly, without a community’s trust, it is difficult for any agency to deliver a workable response. But trust is not merely an attitude in the community, it is a response to the actions of the authorities.

The authorities charged with the response apparently decided to mislead the community. The rumours that information was being withheld, and that the community was being manipulated now appear true. Misinformation did not begin with rumours circulating on social media. It began with the police. Yet again, after a disaster, we see what Bishop James Jones called ‘the patronising disposition of unaccountable power’. Authorities are not trusted because they have proved themselves to be untrustworthy.

As Peter Apps has pointed out, in another of the closing statements, Danny Friedman QC argues that the patronising, controlling, inhumane attitude which we can see here in the Met’s Community Impact Assessment, goes far beyond the Met, and that, at the root of the failures of the response post-Grenfell is that ‘government became anti-social in its indifference’. We hear the echoes of the cries of ‘we don’t trust you!’ as shouted by community members at the authorities at the post-Grenfell public meetings. What will it take for authorities, post-disaster, to treat disaster survivors with the dignity they deserve? Until there is evidence to the contrary, ‘we don’t trust you’ is often a wise position for disaster survivors to take.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment