The test of a workers’ government, like the one of Salvador Allende in Chile 50 years ago, is whether it propels the movement of workers’ and peasants forwards or backwards.

George Kerevan is a Scottish journalist and economist, and a former SNP MP.

Cross-posted from Conter

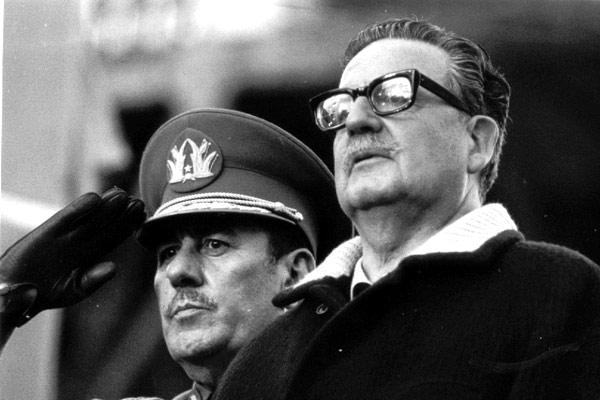

Fifty years ago – on 11 September 1973 – the Popular Unity government in Chile led by the avowed Marxist Salvador Allende (1908-1973) was overthrown in a brutal military coup sanctioned by the United States. For anti-capitalists and socialists of my generation, this was a defining experience.

Half a century on, the Popular Unity (Unidad Popular, UP) experiment deserves serious reappraisal. Given the ebb tide in socialist consciousness and trade union organisation in the 21st century, the possibility of any rupture with capitalism seems likely to begin on the Chilean UP model: an elected, anti-system government at state level, without the initial backing of a mass movement in the streets and workplaces. Such a progressive government might attempt, within its national jurisdiction, to limit or end the power of global finance capital, the energy monopolies, and US, European and Chinese imperialism.

But could such a government go further than mere reform? Would it be able to break with the logic of the global neoliberal and capitalist system without provoking both internal and external resistance on a scale that drove it from office? As it is, international law makes it virtually impossible to nationalise foreign companies exploiting the domestic economy. State subsidies to domestic companies are highly restricted and breaking WTO or EU rules in this area would provoke massive international sanctions. US administrations, even before Trump, have always been quick to impose sanctions against states and foreign leaders who threatened American economic interests.

In this article, I want to draw some lessons for today from the Popular Unity experiment, by way of stimulating a debate about contemporary tactics. At the time, left-wing critics of Allende made invidious comparisons with the failed, anti-fascist, Popular Fronts of the 1930s. I think the intervening half-century has added greater perspective. There are still trenchant criticisms to be made of the Popular Unity episode but equally, there are many positive aspects we can build on. Revolutions – particularly heroic failures such as the Paris Commune or Allende’s Popular Unity – are always messy. Yet at the same time, they are always pregnant with possibilities and challenges to guide the next stage of the struggle.

Finally, I want to offer a modest positive reappraisal of Salvador Allende’s role in the events of 1970-73. On the far-left at the time, Allende was dismissed as a reformist and a roadblock to the success of the revolution. The coup seemed to confirm this analysis. In retrospect, this view seems both sectarian and lacking in nuance. Allende had many faults, both political and personal. But to dismiss him so glibly is to see history through dogmatic political spectacles – and to do so from a safe armchair thousands of miles from the reality of Chile half a century ago.

What constitues a workers’ government?

The classic insurrectionary model of anti-capitalist revolution is not impossible in bourgeois democratic Western industrial nations, though hardly likely except in exceptional circumstances – such as countering a coup (Spain 1936) or overthrowing a dictatorship (Portugal 1974). Much more probable is the election of a progressive government which – by design or default – finds itself being propelled by mass pressure from below along a path of confrontation with the bourgeois order. Of course, not every such government is – by ideology or composition – willing to break with capitalism. In some circumstances (e.g. Germany in 1919 and Portugal in 1976) the formation of a social democratic government acted as a deliberate and conscious break in revolutionary momentum. However, we can posit a model where a genuine workers’ government finds itself in office, one that is prepared to use its control over the levers of administration to advance the anti-capitalist cause by transferring power to the masses. Or more practically, a situation where a progressive government is first elected within the parliamentary system, but which succumbs to mass pressure and ultimately transfers power to popular organs. The question is: what are the circumstances and specific politics that would facilitate such a break with the bourgeois order? To find an answer, we turn to Chile and Allende’s UP government as a laboratory.

The Fourth Congress of the (pre-Stalinist) Communist International in 1922 defined the issue as follows: “The most basic tasks of a workers’ government must consist of arming the proletariat, disarming the bourgeois counter-revolutionary organisations, introducing [workers’] control of production, shifting the main burden of taxation to the shoulders of the rich, and breaking the resistance of the counter-revolutionary bourgeoisie.”

That’s a tall order, effectively the equivalent of instituting the class dictatorship of the proletariat. But the Comintern debate was very nuanced. It saw a workers’ government as a transitional and transformative mechanism in its own right, with its own laws and political dynamic. Which is why the concept has significant meaning today. As the Comintern resolution explained: “Even a workers’ government that arises from a purely parliamentary combination, that is, one that is purely parliamentary in origin, can provide the occasion for a revival of the revolutionary workers’ movement… The slogan of the workers’ government thus has the potential of uniting the proletariat and unleashing revolutionary struggle.” (My emphasis).

In other words, a workers’ government – even one arising accidentally from the parliamentary process in advance of popular mobilisation – can detonate a mass struggle for socialist objectives. For instance, the hypothetical election of a progressive Scottish Government after independence which finds itself responding to economic sabotage from London. Or, however unlikely, the election of a Corbynesque Labour government at Westminster. Certainly, an electoral victory for any anti-system electoral front assumes the working class and its allies must have been mobilised to some extent beforehand. However, there is always a dialectical interplay between the mass movement and the elected workers’ government. It might be that the masses have such illusions in their electoral victory that they demobilise, expecting the new left-wing government will deliver change on its own. Alternatively, as in Chile, the election victory might occur after the mass movement had begun to ebb somewhat. In this case, Allende’s unexpected victory in the 1970 presidential election gave the mass movement new hope.

With this perspective in view, the Comintern stated: “Under certain circumstances, Communists [i.e. anti-capitalists in today’s terminology] must state their readiness to form a workers’ government with non-Communist workers’ parties and workers’ organisations. However, they should do so only if there are guarantees that the workers’ government will carry out a genuine struggle against the bourgeoisie…” [My emphasis]

In other words, the anti-capitalist forces should not simply criticise from outside, but be prepared to work with progressive forces at a parliamentary level if (and only if) there is agreement on “a genuine struggle” for concrete, anti-system measures. That could involve workers’ control to decarbonise the economy. It could include leaving Nato and removing foreign nuclear weapons from Scottish soil. It could include imposing punitive taxes on big oil and taking land into community ownership. Above all, it would include transferring power from the capitalist state and parliamentary apparatus to popular, elected institutions. The strategy would be to use the parliamentary foothold as a lever to excite popular resistance and then hand over power to the organs of popular resistance as they emerge. This model is not about effecting reforms from on high but instead dismantling the system from within; and using the fulcrum of the bourgeois state -money, media apparatus, prestige, and so forth – to aid popular revolt.

Note that none of the above precludes a struggle between factions within the Workers’ Government over the way forward – between those who want to progress the revolution and those who wish to divert it along reformist channels. Indeed, it is the interplay between the evolution of the Workers’ Government and the mass movement that is the focus of our reappraisal of the UP experiment.

Was Popular Unity a popular front or a genuine workers’ government?

Given its ultimate failure, there are critics of Popular Unity who dismiss it as a classic Popular Front: an alliance between the workers’ parties and parties of the liberal bourgeoisie, with a conscious aim of defending bourgeois democratic institutions against fascist reaction, but thereby consciously barring any move towards the overthrow of capitalism. In the 1930s, Popular Fronts deliberately opposed any anti-capitalist actions lest they fracture the cooperation with the liberal bourgeoisie against Fascism. The Stalinist Communist Parties in particular acted as brakes on revolutionary developments to the extent of sabotaging the Spanish Revolution and diverting workers’ political struggles in France into purely economic (wage) demands.

Popular Unity was premised on a wholly different – though flawed – strategy. Allende himself had been health minister in the 1938 Popular Front government in Chile, which was dominated by the liberal bourgeois Radical Party. Allende was more aware of what is meant by a Popular Front than latter-day armchair critics. Here is what Allende said in conversation with the French activist Régis Debray in 1971:

“…the Chilean Popular Front [of 1938] did not set out to bring about the revolutionary transformation of Chile… By contrast, today, as our programme shows, we are struggling to change the system, and this is completely different… I have reached this office to bring about the economic and social transformation of Chile, to open up the road to socialism. Our objective is total, scientific, Marxist socialism.”

One can accuse Allende of being deluded. One might also accuse him of lying, though accusing someone who died opposing a CIA-supported coup should not be done lightly by armchair critics on the other side of the planet. More to the point, for Chile’s elected president to proclaim publicly that he wanted to lead a Marxist revolution against capitalism is to invite the masses to seize their factories and land. Which, of course, is what the Chilean people proceeded to do in the years 1970 to 1973. If that is not a textbook example of the early Comintern definition of the role of a workers’ government, I don’t know what is. Whatever genuine criticisms we can make of the UP experiment, to confuse it with a classical Popular Front is incorrect, unscientific, and frankly preposterous.

We should note from the outset that the UP government included representatives of nominally bourgeois political formations, such as the liberal Radical Party, and even forces breaking from the right-wing Christian Democrats, i.e. MAPU. Trotsky and the later Trotskyist movement went so far as to define a Popular Front specifically as a coalition containing workers’ and bourgeois representatives. For Trotsky, it did not matter that the bourgeois ministers were in a tiny minority or represented ‘phantom’ parties. That was the whole point. Bourgeois ministers, however nominal, represented a promise to the ruling class that the Popular Front would not unleash the revolutionary energies of the proletariat and peasantry. Bourgeois politicians were there to provide an excuse for the socialist and (especially) Stalinist representatives to abort any revolutionary initiatives from below – to the point in Catalonia in 1937 of using armed force to liquidate physically the anarchist and revolutionary Marxist parties.

By applying this legalistic and narrow definition of what constitutes a counter-revolutionary Popular Front, many leftist currents were quick to denounce the UP government from the day of its inception. That included all the factions of the Trotskyist Fourth International, whose United Secretariat issued a unanimous statement in December 1971 which accused the UP government of “class collaboration with the bourgeoisie” and of maintaining “the basic economic structure of capitalism”.

In reply, let us quote from Popular Unity’s electoral programme of 1970. It begins: “The popular and revolutionary forces have not united to struggle for the simple substitution of one president of the republic for another, nor to replace one party for another in the government, but to carry out the profound changes the national situation demands based on the transfer of power from the old dominant groups to the workers, the peasants and the progressive sectors of the middle classes of the city and the countryside…”

The UP programme goes on to proclaim it will “transform the present institutions so as to install a new state where workers and the people will have the real exercise of power… The police force should be reorganized so that it cannot again be employed as a repressive organization against the people… The united popular forces seek as the central objective of their policy to replace the present economic structure, putting an end to the power of national and foreign monopolistic capital and of latifundism in order to begin the construction of socialism.”

There follows a set of concrete steps that a UP government will implement: “The first step will be to nationalize those basic sources of wealth such as the large mining companies of copper, iron, nitrate and others that are controlled by foreign capital and internal monopolies…. Acceleration of the agrarian reform process by expropriating those fields that exceed the maximum established size… To liberate Chile from her subordination to foreign capital. This means the expropriation of imperialistic capital…Complete civil capability will be established for the married woman as well as for the children within or outside of marriage as well as adequate divorce legislation that completely safeguards the rights of the woman and the children…”

We can criticise the UP programme for eclecticism and other defects. But this is a very different project than, say, the classic Popular Front in France in 1936, whose programme was limited for the most part to meaningless platitudes such as calling for “the collaboration of the people and in particular the working masses for the maintenance and organization of peace.” The few concrete measures in the French Popular Front programme involved nationalising the defence industries (which sections of the ruling class favoured, as a move against Nazi Germany) and the outlawing of paramilitary groups. The latter were mostly fascist, but it should be noted this was a general provision that also disarmed the proletariat.

The French Popular Front programme also delivered some temporary trade union and social concessions, plus there was a half-hearted reform of the privately-owned Bank of France, the central bank, to stop it from imposing austerity on the economy. But overall, there was no attempt to nationalise credit or heavy industry or to introduce workers’ control. Infamously, the Popular Front was so wedded to supporting the League of Nations and placating the French and international bourgeoisie, that it refused to provide arms to the democratically elected Republican government of Spain after Franco’s coup. The Popular Front pointedly did nothing about decolonialisation, except for a face-saving commitment to hold a parliamentary inquiry into conditions in France’s overseas possessions.

The French Communist Party – a Popular Front signatory but which refused ministerial office – used the excuse of maintaining “national unity” to sabotage and curtail the wave of spontaneous strikes the Front’s election had triggered. As a result, the French working class was deliberately demobilised and demoralised by its own leadership. The PCF was acting as an agent of the Stalinised Soviet regime to show Western bourgeois leaders that Moscow had no intention of overthrowing French capitalism. This was vital to Stalin’s diplomatic offensive to build an alliance with the Western imperialisms against the rabidly anti-communist and revanchist Nazi regime in Germany. Ditto Stalin’s strangling of the revolution in Spain.

We need to remember that classical Popular Fronts were an extension of Stalin’s foreign policy, not products of French or Spanish domestic politics. This is a very different trajectory to the Popular Unity workers’ government in Chile, even though the Chilean Communist Party, as a major component of Popular Unity, proved a consistent brake on revolutionary measures. True, this latter policy was also a reflection of Soviet diplomacy and so-called “peaceful co-existence”. However, on a balanced judgement, the Nazi threat to Stalin’s regime was existential, while the peaceful co-existence project was a pitiful attempt to persuade Washington to leave the ailing, decrepit Brezhnev to wither away quietly – a forlorn hope.

The UP coalition and the class nature of the Chilean Socialist Party

Allende’s Socialist Party was never a social democratic, reformist organisation in the classic European style. Founded as late as 1933, the PS saw itself as a Marxist party that rejected control by Moscow. Often virulently. The founding statement of principles says: “The Socialist Party embodies Marxism… Capitalist exploitation based on the doctrine of private property must be replaced by an economically socialist state in which said private property be transformed into collective ownership… The new socialist state only can be born of the initiative and the revolutionary action of the proletarian masses… The socialist doctrine is of an international character… The Socialist Party will support their revolutionary goals in economics and politics across Latin America in order to pursue a vision of a Confederacy of the Socialist Republics of the Continent, the first step toward the World Socialist Confederation.”

True, the PS thereafter remained an organisational and ideological muddle and was bedevilled by factional infighting and expulsions. Above all, it was characterised by bouts of opportunism which led it to join bourgeois and petty bourgeois governments, most of which were short-lived. However, starting with the legalisation of the Chilean Communist Party in the 1950s, and the rapid development of Chilean capitalism in the 1960s, a process of unification and cooperation began on the left. This process recomposed the PS and put it at the head of the resurgent popular movement, under the leadership of Allende.

As for Salvador Allende himself, in fairness, we should not characterise him either as a social democratic reformist or a bourgeois liberal. He stands more in the tradition of the centrist Marxist leaders of the Second International like Kautsky, rather than a conscious reformist like Bernstein. Allende remained a Marxist, an anti-capitalist and very much an anti-imperialist. Certainly, he was not a Leninist. His conception of making the rupture with capitalism was predicated on winning a popular majority within the state structures and eroding and subverting these structures from within, using the weight of the popular masses. In this, he followed (somewhat unconsciously, I think) the strategy of Kautsky post-1910. In modern times, Erik Olin Wright, the late American Marxist sociologist, also proposed a similar strategy of using what he termed “the contradictions” within the bourgeois state to secure degrees of popular control during a crisis – he gave the example of the struggle to reverse climate change.

The test of a workers’ government: forwards or backwards?

Did the election of the Allende presidency in 1970 propel the workers’ and peasants’ movement forward or backward? This is the basic material test of a Workers’ Government, not a scholastic debate on the involvement of bourgeois ministers. The SPD government in Germany elected in January 1919, which had bourgeois ministers, was definitely a step backwards from the interim government of the year before, which had been appointed by the first workers’ councils. The January SPD government was consciously counter-revolutionary and colluded with the officer corps to physically liquidate Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Clearly, we are not talking about a Workers’ Government in this case.

The UP government, on the other hand, nationalised the banks and US mining companies and facilitated the growth of the organs of popular power. UP also undertook the first-ever experiment in real-time economic planning and coordination using computers. With the aid of the MIR grouping, an ultraleft Guevarist tendency with roots in the Chilean peasantry, the Socialist Party took steps to arm itself and workers’ militias. There are serious grounds for criticising Allende’s failure to accelerate the growth of popular power or to take more radical steps to dismantle bourgeois military structures that eventually precipitated the coup, especially the Air Force. But these are criticisms of a different order than simply dismissing Allende as a bourgeois stooge. The dialectic of the struggle of the Chilean masses in 1970-73 requires a deeper understanding if we are ever to profit from their heroic failure.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment