Is another form of capitalism possible? And can new social movements like Extinction Rebellion escape the ideologies that pervade our lives?

George Monbiot is a British writer known for his environmental and political activism

Cross-posted from Open Democracy

If you get into debt buying your child branded trainers, if you fear redundancy, if you suffer anxiety about the future of the planet and you blame yourself for all of these things then you are showing symptoms of drowning in the “insidious” and “sinister” ideology of neoliberalism.

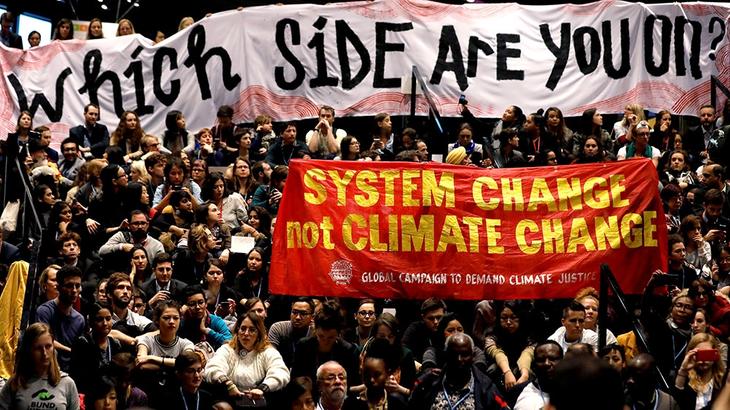

The escalating environmental and social crises that confronted us – climate breakdown, collapse in biodiversity, the threat of war – are all failures of a worldview that puts profit making, the markets and economic growth ahead of human happiness. This is George Monbiot’s prognosis.

The journalist and campaigner will be speaking at a three-hour special event at the Gillian Lynne Theatre in London on 11 February 2020 under the title The Invisible Ideology Trashing Our Planet. The tour will continue on Thursday, 12 March 2020 at the UBSU Richmond Building in Bristol.

The invisible ideology referred to is neoliberalism. But when I caught up with Monbiot at his home in Oxford this month he had already extended the scope of his speech to include capitalism and consumerism. This is the holy trinity: capitalism is the father, consumerism the son and neoliberalism the holy ghost.

Monbiot argues that capitalism now is neoliberal capitalism. And, unusually, that capitalism and consumerism are ideologies as much as neoliberalism is. “Part of the insidious power of these ideologies is that they are the water in which we swim – the plastic soup in which we swim. They are everywhere. They affect our decision making every day, they affect the way we see ourselves. They are difficult to see not because they are so small but because they are so big. The most powerful ideologies never announce themselves as ideologies. That is where their power lies. Our first step is to recognise them as ideologies.”

The blasphemy of attacking capitalism

Why did it take Monbiot so long to come to attacking capitalism head on?

“There was an element of fear involved. Directly attacking capitalism is blasphemy today. It’s like pronouncing that there is no god in the 19th century. But of course we recognise those who did so as pioneers whose voices were necessary. I suddenly realised that for years I had been talking about variants of capitalism. I had been talking about corporate capitalism, neoliberal capitalism, crony capitalism. But then it suddenly struck me that maybe it is not the adjective, but the noun. It makes a difference, the form of capitalism, but all forms drive us to the same destination, albeit at different rates. So neoliberal capitalism accelerates natural destruction. But Keynesian social democratic capitalism still gets us there, but maybe a little more slowly because it has more regulatory involvement and less inequality.”

Neoliberalism, broadly, asserts that free market capitalist is the best mechanism for making decisions in our modern, complex societies. The state should not intervene. This means fewer regulations, from banking to food. It means not providing health and social care. It means cutting taxes. Neoliberalism dominates the thinking of the world’s leaders, at a time when it undermines the efficacy of the state to deal with climate breakdown.

So is a non-neoliberal capitalism now possible? Could John Maynard Keynes, the influential economist who advocated government management of the economy, make a return? Can we stage a tactical retreat? Or has capitalism reached a point where neoliberalism red in tooth and claw is necessary for capitalist profit generation?

“We cannot go back to [Keynes],” Monbiot responds. “It is growth based. The whole point of Keynesian economics is to maintain the rate of growth – not too fast, not too slow – and we know that even a steady rate of growth is progress towards disaster. But also, in its first iteration in the years after the Second World War it was very effectively destroyed, principally by finance capital working out ways to destroy capital controls, foreign exchange controls. The idea that we can relaunch a Keynesian capitalism and not have it destroyed by people who have already destroyed it once, who have not forgotten those lessons, and who are in a much more powerful position to destroy it today….that’s just dreaming. That is magical thinking. You cannot go back in politics, you have constantly to devise new models.”

On Extinction Rebellion, citizens’ assemblies, and the taking of political positions

I ask Monbiot what all this means for current debates around climate advocacy and campaigning and particularly for Extinction Rebellion (XR).

He hesitates for a moment, not wanting to “abuse” his position as Britain’s most influential environment journalist to sway the climate direct action movement.

“As I see it, XR tried very hard to remain a single issue movement and to say, ‘we are not taking a justice position, we are not going to take a political position, we just want people to respect the science and introduce the policies that are in accordance with the science’. I understand that, because they wanted to reach as many people as possible.

“But there is obviously a tension between that and the intersectionality that our many issues demand and the necessity to understand the political context in which we operate and the political change required in order for us to operate. I do not think we need to flinch from the fact that to take effective action on climate breakdown requires a change of leadership, a change in government, it requires political change and it very much requires ideological change. We fool ourselves if we think we can change the policies without attending to the political framing in which these policies are discussed.

He adds: “These have to be political campaigns as well as environmental campaigns. There is a lot of recognition [within XR] about where the constraints have been and lots of intelligent people having great conversations about how it evolves. It cheers me to see so many interesting discussions happening.”

So, I ask, does XR need to be anti-neoliberal?

“Obviously, if anything XR wants to happen is to happen, then we have to overthrow neoliberal ideology. The idea of government being so activist that it is going to transform our whole economy and go to zero carbon by 2025, and change our political system, even acknowledge the importance of a political system in making decisions, all that is directly counter to neoliberalism. If a political scientist was to analyse XR’s three demands and its charter they would say, this is a profoundly anti-neoliberal programme’.”

I asked whether neoliberalism also presents a challenge in terms of the XR proposal to have a citizens’ assembly with members chosen through sortition (which is similar to the way we select members of a jury in the criminal justice system). If neoliberalism is hegemonic, is all pervasive, then even the great British public will be trapped within its assumptions. Monbiot points out that the civil service will also be immersed in, and will have an interest in upholding, neoliberal ideology.

“I have never been in favour of a pure sortition system,” Monbiot responds. “What it does is give tremendous power to the civil service, because the civil service are the permanent officials who understand how the system works, who have a long term stake in that system, whereas the people who are chosen by sortition haven’t. T[he citizens] are not trying to get in at the next election – they will not have a long term political programme. That makes the bureaucracy tremendously and dangerously powerful. A mixed system – in the widest possible sense – has got more to say for it.”

Can we ever escape ideology?

So the question arises: can we ever escape ideology? Karl Marx, the philosopher communist, believed that through a rational, logical, analysis of the economy and of society he had punched through “bourgeois” or capitalist ruling class ideology and glimpsed momentarily a non-ideological reality. But if we argue that we are not ideological, that we are free entirely of any illusions, is this not proof positive that we are so deeply immersed that we cannot even see the edges of our own delusion?

“I don’t think you can be [ideologically free]. We’re so governed by our social environment, and our social environment will always be saturated by ideology. To be ideology free would be to become an island, you would have to be completely isolated from all other human beings – and even then you would probably create your own ideology. You often hear people stand up and say, ‘I have no ideology’. And that is just self-deception.”

Monbiot presents a compelling argument. We say our goodbyes and I am back out on the street, reflecting that I am even now contained entirely within ideology, neoliberal ideology. I am willing to believe that we will never escape ideology – a grand narrative that explains who we are, where we are, what we are. If this is the case, we as individuals and as a collective humanity must choose our ideology wisely.

Brendan Montague is editor of The Ecologist. A feature based on this George Monbiot interview – focused on the history and rationality of neoliberalism – will feature in the next issue of Resurgence & Ecologist magazine.

Be the first to comment