The House of Couriers opened in December to aid rider-organising in the Belgian capital. The Gig Economy Project went to the House of Couriers to speak to two of its main organisers to find out more. (Interview conducted jointly with Anne Dufresne from Gresea.)

The Gig Economy Project is a media network for gig workers in Europe. Click here to find out more and click here to get the weekly newsletter.

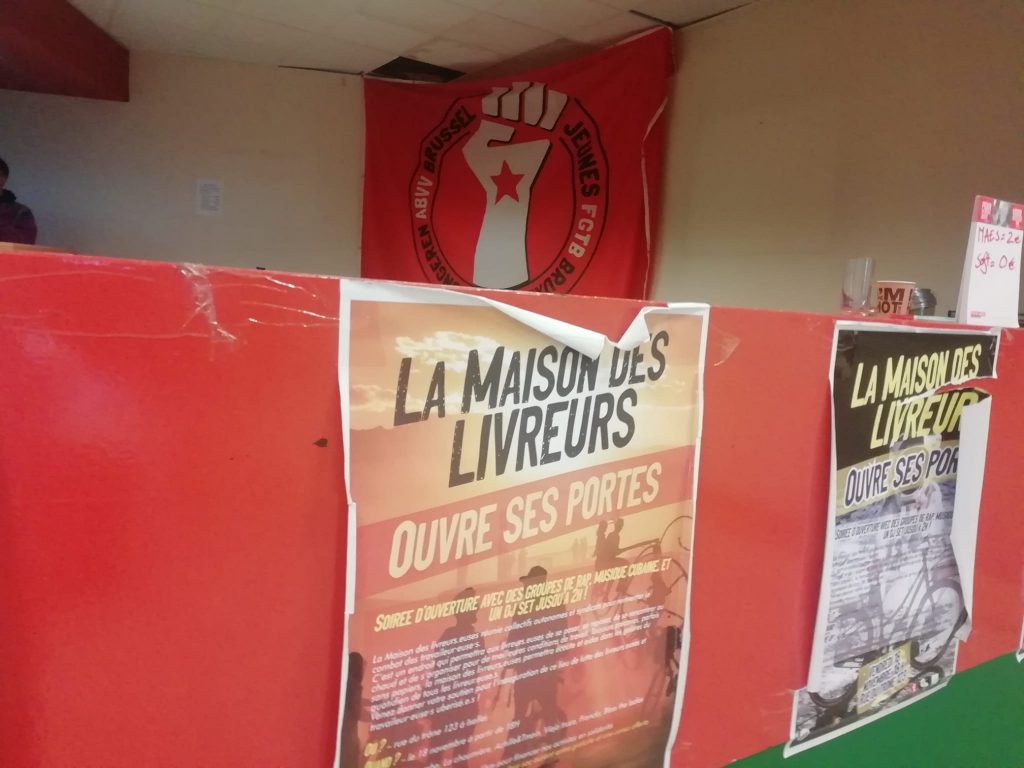

‘La Maison des Livreurs’ (House of Couriers) in Brussels has all the vibes one would expect from a centre for workers organised from the bottom-up. A pingpong table and sofas sit in the middle of a sparsely populated hall. Posters and union flags adorn the walls. The building is under long-term occupation by another group of activists, making it one of the few affordable places for the ‘Collectif Coursiers Bruxelles’ (Brussels Couriers Collective).

“We are not really a union so we don’t have a lot of money,” Camille, who has been a rider for five years and is one of the stalwarts of the House of Couriers, tells the Gig Economy Project. “They offered us access to this space, and it’s good because it is in connection with the people living here, and lots of different associations use the building.”

Camille still rides for about 20 hours a week for Uber Eats, but most of his work is unpaid: he spends about 40 hours a week volunteering for the House of Couriers, representing riders who have had their account deactivated or have had an accident and are trying to get insurance to pay out. Part of his activism includes media appearances: he has to rush off from our interview to speak on TV.

The recent death of an Afghan rider, Sultan Zadran, on the streets of Brussels has been a tragic talking point. Zadran was a rider for Uber Eats, but the company claims he wasn’t working at the time of his fatal accident.

“We strongly believe he was doing a delivery at that point, because of where the accident took place and how it took place,” Camille says. “We have to contest Uber’s claim, but it’s very difficult because obviously we cannot access his phone.”

The House of Couriers (HoC) in Brussels is one of several to spring up across Europe over the past two years. Platforms do not offer food delivery couriers a physical location to meet, rest and use the toilet, so a HoC provides a much-needed space for riders, as well as acting as a hub for worker organising.

The Brussels HoC launched in December 2022 and is currently open three days a week. It’s main function is to represent riders who come through the door and ask for help. So far, 150 riders have come in need of assistance.

“Now that the place is well known we will have people waiting here to speak about their situation,” Camille, who moved to Brussels from France half a decade ago, says. “Mostly the problem they have is the blocking of an account, and we speak to the platforms, like Uber Eats, which don’t really agree to a clear channel of communication and we are struggling with that. That is why we went inside the offices of Uber Eats to protest.”

Uber Eats still refuses to officially recognise the Collective, but the protest in February produced results; many of the riders subsequently had their accounts re-activated.

“The unlocking of the apps is the best part for me and that is where we are most effective,” Camille explains. “When a rider texts me and says ‘thank you for what you are doing, I can now work again and fill up the fridge’; that is rewarding.”

“We try to work intelligently”

There is a stark contrast within platform work organising in the Belgian capital: while the Couriers Collective has to occupy Uber’s offices to get their attention, the union UBT-FGTB has an official permanently stationed in Uber’s Brussels hub. UBT-FGTB signed a controversial recognition agreement with Uber last year which committed the US platform giant to little, and the Couriers Collective are not shy about expressing their opposition to it.

“We have one section of the FGTB which works with us, the youth section, then another part of the union are working with Uber, so it is an issue,” Raphael, an activist at the HoC who recently stopped being a rider after two and a half years at Just Eat, tells GEP. “There’s a struggle to be seen as representative and to be the ones who are talking to Uber as representatives of the workers.”

The House of Couriers is reliant on trade union support to pay the rent, and the unions send officials to the HoC one or two days a week to help the Collective with addressing the grievances of the riders. Camille says it’s a balancing act between making most use of the resources which unions have while maintaining the Collective’s independence.

“We try to work intelligently: we want to involve the unions in our work, but we do not want to be eaten by the unions,” he says.

While maintaining the Collective’s autonomy is important to Camille and Raphael, they are not unaware of the limitations of organising on an entirely voluntary basis over a sustained period of time. The Collective appears to be doing all of the time-consuming grunt work of a union, but without any of the membership fees which facilitate the day-to-day work of unions.

“We need more people involved,” Camile says. “If we take the example of the Paris House of Couriers, where the municipality pays for a lot, there is one person who is paid to be there and to offer support to the riders.

“All the people that work here also work on other projects. And we don’t get paid to do this, we need to work, and we cannot always be here during all of the week.

“I don’t know if it should be the unions or the council administration, but we really need more people getting involved in this project to have more time for the workers.”

Raphael, who is also a French migrant, says they would like to add bike repair and other dimensions to the HoC, but the main ambition is to sustain the project.

“There’s lots of effort being put into it, which is great, but it requires a lot of involvement of just a few people,” he says. “What we want is a collective that can outlive the people who are doing the organising right now, that can keep going even with completely new people, because there is a real need for this.”

The issue of turnover is a constant thorn in the side of worker organising in food delivery. Workers tend to move in and out of this sector very quickly. Before Raphael and Camille moved to Brussels, a previous generation of riders had established the Couriers Collective in the city, but they have since moved on.

“We try to make the link between the different generations,” Camile says. “The first generation is now working at university on this topic.”

Political questions

It is in Brussels where potentially the most important legislation to regulate platform work so far is being drawn up. EU member-states remain locked in battle over the draft Platform Work Directive. Meanwhile, the Belgian Parliament passed a very similar law to the European Commission’s proposal for the Directive in January, but it has failed to have any effect on the working lives of Camille and the other riders so far, as the platforms claim they don’t meet the employment criteria stipulated in the law. Camille has grown to be sceptical of politicians bearing gifts.

“With the Belgian law, it was a big announcement saying it would be a better situation for the workers. We have seen already these types of announcements in other countries. But the law cannot be applied at the moment because it requires action from the executive to put this in place,” he says.

“On the European law, we see the big work of the platforms to avoid the employment criteria. We are a bit scared that the legislator is going to do something whereby the status quo is going to be maintained.”

Camille also highlights the issues that even a strong Directive are unlikely to address, like the situation of undocumented riders that do not have the right to work, and the use of racist facial recognition technology. The day before our interview, the Couriers Collective joined and spoke at a demonstration against racism in the city.

“Mainly the riders are first or second generation migrants,” Raphael says. “The time when it was all white people who enjoy cycling doing these jobs is long gone.”

As political issues go, a key one on the mind of the Couriers Collective right now is the future of the controversial ‘P2P’ status in Belgium – a tax regime introduced in 2018 to regulate occasional work performances. Eighty per cent of Belgian riders are P2P, but it is potentially going to be scrapped. Camille – who spends much of his time helping riders who are having problems with the problematic P2P system – fears if it disappears overnight it could lead to thousands of riders being de-activated from the app.

“In Paris there was a big wave of disconnections, about 3,000 people, and it could be even more in Belgium if there is a sudden disconnection of P2P,” he says.

One suspects the House of Couriers will continue having to deal with the fallout of bad legislation for some time. This grassroots trade unionism may be held together by a small number of volunteers, but it has proven to be effective in supporting riders struggling to cope with the twin dangers of uncaring algorithmic management and Brussels’ busy streets. Better under-resourced worker-organising that fights, than well-resourced unionism that obeys.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment