Rasmus Emil Hjorth, Danish rank-and-file Wolt courier in the Wolt Workers’ Group, reports from Berlin, where he has been helping the Lieferando Workers’ Collective as the couriers elect their first Works’ Council

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy. If you have information or ideas to share, please contact Ben on GEP@Braveneweurope.com.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in Europe is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Andrew Wainwright Reform Trust.

I arrive at a polling station in the Ostkreuz area of Berlin. The outer interior looks like an old squatted house, one which would make Bumzen (a legalised squat in Copenhagen) turn pale.

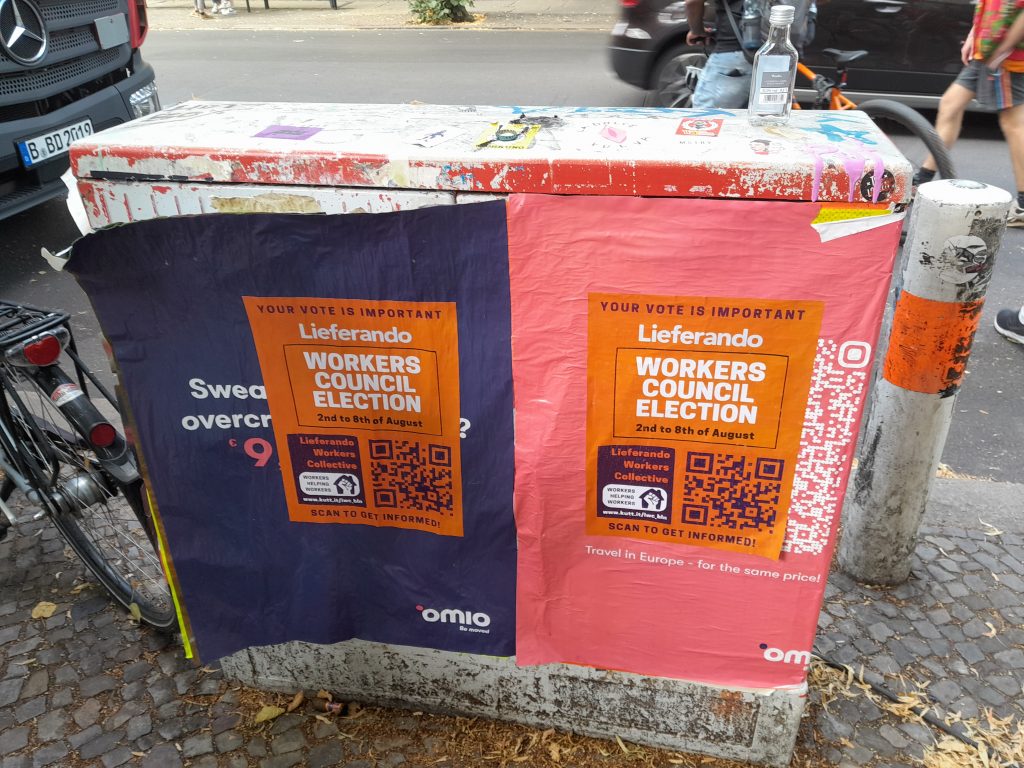

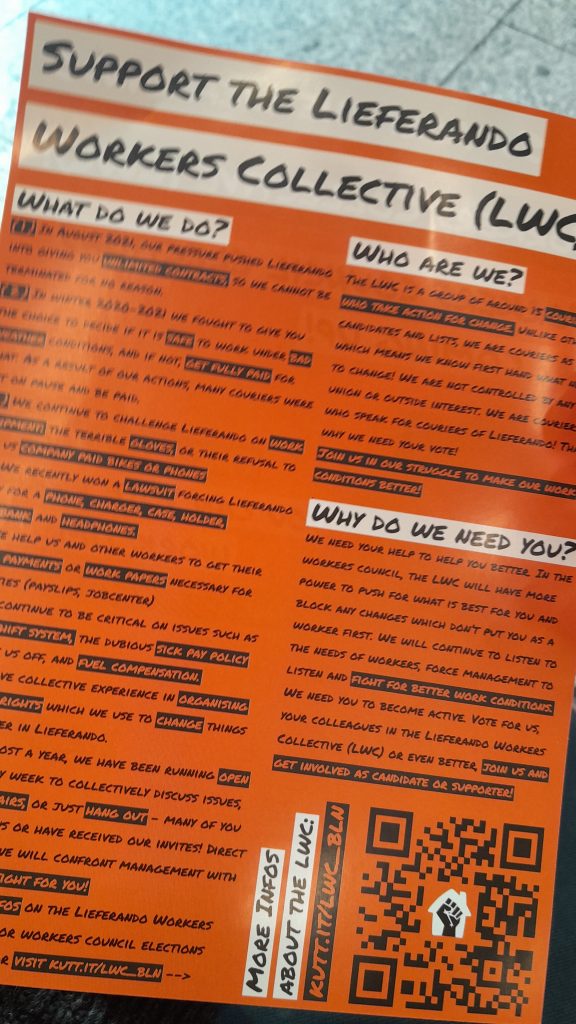

It’s one of the last election days for the Works’ Council at Lieferando, which is the German branch of Just Eat Takeway. I’m volunteering, helping the self-organised group Lieferando Workers’ Collective (LWC) with their election efforts.

When I told my Danish friends that I had departed to participate in a Works’ Council election, they found the concept alien. Few of my friends knew what a Works’ Council is, and those who did know, only understood it in a Danish context.

Works’ Councils operate differently in Denmark, where they’re seen as less powerful tools for workers. That is because our collective bargaining agreements play a stronger role in organising. The concept of the Works’ Council is something you find in many places in Europe. It’s an organ where both workers and employees meet. The intention of the Council is for workers to get informed about current operations, but ultimately also manage decisions, in cases where there are no conflicts of interest. Frankly, it seems to me the Danish Works’ Councils are only areas of captive hearings, not of equal participation.

I have discovered that Works’ Councils (WC) have a different meaning in the German context. The German couriers use the WC in their organising efforts.

While I was helping with the election, there was this constant notion of visible and open confrontation from the food delivery company. The delivery bosses’ democratic mindset is questionable. There’s a clear tendency, that every time any courier starts to call for elections for a WC, employers try to spoil the process. The fight for democratic participation in the workplace, therefore, is not only fought in the workplace but also in the German courtrooms.

The couriers whom I have spoken to say that management uses the court filings as a kind of union busting mechanism. It was the same with the Lieferando elections, where 1600 couriers are eligible to vote. Right before the election, Lieferando filed a case against the couriers’ election lists. Shortly after, the labour court dismissed their claims.

The german food couriers and the labour movement

The election list that I am helping to campaign for, LWC, is not a union, it’s a rider-affiliated collective. It cooperates with unions, but with an arm’s length principle. The collective wants to stay autonomous.

The German labour movement, like Denmark, is sometimes seen as a black sheep. The general critique of the union movement in Denmark, which is losing members, is that they’re as likely to be seen spending money on advertisements at football matches as they are on organising projects. Members are left with a feeling of being forgotten in large sectoral agreements, where a union staffer, who is far away from the members, negotiates an agreement.

Ordinary workers find other places to go. This is a particular problem in our transport sector. This happens because some of the more craft oriented unions want to legislate problems away, or make bad standardised deals, where they essentially contribute to the platform’s lobbying efforts. A recent example of this is the GMB union in the UK, which has signed a “historic” deal with Deliveroo, where couriers are not represented by a collective bargaining agreement but are “acknowledged”.

At the top level, the union movement is embarrassingly distant from the work of the LWC. In a recent report from the European Trade Union Institute (ETUI), senior scholar Kurt Vandaele writes of rider-affiliated groups that their “effectiveness and sustainability…remain to be seen”.

The thoughts of scholars and union staffers seems to be that rider-affiliated groups might become a bursting bubble. But the situation is quite different. The couriers have created a living network without any central programme or dues. They’ve built a network across different delivery companies. These networks are based on knowledge of which warehouses or fleets are strategic. Rank-and-file workers and a small pool of sympathisers keep everything flowing. The chief idea is that these Works’ Councils can create a more permanent area of decision-making for couriers across the whole sector. LWC’s activists have been among the chief organisers of this strategy, where they have picked up and assisted in campaigns led by couriers in other companies.

The couriers from LWC see the WC as a key instrument in ending the exploitation of couriers. Through the WC elections, the couriers get protected against termination in an election cycle of four years, which provides a strong base for organising. This is much more advanced than the organising strategies I have witnessed in Denmark. In some sectors, we only think of trying to protect our current conditions, not in ways of bettering them or expanding. In Germany, they think differently. Even with just two or three rank-and-file activists at a warehouse, a call for elections is almost guaranteed.

Two election lists fight for elected positions

The election days are a big coordination effort. We had to physically go out and get the 17 polling places covered. It became a great manhunt for couriers.

LWC were not the only ones running for election on a list. There was another list called “Drivers and Riders United”, which was supported by the union for kitchen staff and food, NGG.

The two lists disagreed on some points of contention, which were not so much expressed in the election material, but more fundamentally about how they wanted to exercise a Works’ Council mandate. As part of the criticism, the LWC was worried that the NGG list had too close a relationship with Lieferando, especially because a mandate led by them would threaten LWC’s position in the workplace.

The real tension is about where the organisation in the workplace must take place. NGG would like to use the Works’ Council to draw up a long-term collective agreement with management. On the otherhand, LWC has not felt very well represented in the union. The paying of union dues is a big issue; LWC do not want to pay money which is then used somewhere else. The final straw was when a member of the LWC was visited by a debt collector because NGG wanted to collect a debt. NGG was therefore not referred to by LWC as an alternative list from the rank-and-file, and instead was seen as something that came from outside.

But the election campaign itself was peaceful. There was not much trouble and generally, the voters were quite satisfied. The coordination work and having to find couriers took me all over Berlin. We stood for hours in front of a McDonald’s just to talk to two couriers. But it was worth it. On Friday, the results arrived. However, the turnout was not record-breaking; the couriers knew that with demand falling in the summer, getting 200 couriers to vote was a good result. LWC won a strong majority, with 131 votes versus 68 for the NGG list.

Solidarity unionism

This is called solidarity unionism. Everyone’s workplaces must be defended, even those you don’t know. That is why the activists get involved in organising even in workplaces they are not part of. With the collective bargaining agreements in Denmark, we will see similar example of activists that are involved across different areas and industries. The Danish network ‘arbejdere I bevægelse’, which has stood wide and steady since 2017, engages their colleagues to become active in their workplaces.

However, I think it is important to recognise the work of these grassroots groups. They are not counterparts to the trade union movement, but active parts that put the industry’s real issues on the negotiating table. In my main organisation, the International Transport Federation, young transport workers have agreed to the inclusion of the rider-affiliated collectives.

To sign up to the Gig Economy Project’s weekly newsletter, which provides up-to-date analysis and reports on everything that’s happening in the gig economy in Europe, leave your email here.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment