The pandemic has accelerated the growth of the data economy and the digital giants who dominate it. It’s time to rethink how data is owned, governed and used.

James Meadway is an economist and writer

Cross-posted from openDemocracy

Gerailt (public domain)

On 31 December 2019 the Wuhan Medical Health Commission informed the World Health Organisation of a new form pneumonia, of unknown cause, that had struck three patients.

Six months later, with 14 million reported cases worldwide, over 650,000 deaths, and more than three billion workers worldwide in countries affected by lockdowns, we remain in the early stages of the COVID-19 crisis. There is no plausible return to a pre-COVID world: a safe and viable vaccine has yet to be developed, and despite some very promising early results the problems of production and distribution for a successful vaccine have yet to be solved; immunity to this disease may be very short-lived, as it is with other coronaviruses; and, were we to escape COVID-19, the increasing incidence of epidemics from novel diseases – the result of the immense pressure modern, capitalist economies are placing on the world’s ecosystems – makes the chances of future outbreaks more, not less, likely. The future as we might have expected it has been cancelled, and the past is not returning.

There are, nonetheless, some clear continuities. One of the most striking is the accelerating growth of the data economy and, with it, the rapid expansion of the digital giants who dominate it. As Creating the Digital Commons a new report from the IPPR (Institute for Public Policy Research) makes clear, the data economy was already of an immense size. Approximately 25 quintillion bytes of data were created every single day, ahead of the pandemic, and that volume is growing exponentially. To put it in perspective, by 2017 90% of the world’s data had been created in the two years’ preceding. This expansion of the sheer scale of the data economy brought with it the overwhelming domination of the very few companies managing this growth.

Predominantly US-based, the platform giants had, in the ten years since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, grown to become the world’s largest companies by value. The collection, processing, and application of data had shifted companies like Google, Amazon or Alibaba into positions where virtually no other part of the economy (or society) was left untouched by their operations; Artificial Intelligence (AI), based on machine learning techniques themselves dependent on the processing of vast quantities of data, and the expansion of 5G and the “Internet of Things” are set to reinforce this domination.

The pandemic and the data economy

That was before the pandemic hit. There are two major routes through which COVID-19 has accelerated the growth of the data economy. The first, and perhaps the most obvious, is in the imposition of social distancing measures, most dramatically in the form of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders, which have seen an extraordinary transfer of activity online. At the height of the first UK lockdown in May, 49% of British employees reported that they had worked exclusively from home in the previous week – up enormously from the 5% who reported regularly homeworking in 2019. The possibility of homeworking varied enormously by sector, but nonetheless the impact was clear: broadband use rose dramatically across the globe during the first months of the pandemic, with BT reporting 60% more data being uploaded and downloaded over its own network.

The other element of the increase in data use is less obvious, but nonetheless persistent, and this is the expansion of medical monitoring as part of the expansion of biosecurity measures in the wake of the pandemic. Some of these are well-known, and subject to major public debate, like the attempted implementation of contact-tracing software reliant on very widespread mobile phone use, and, where relatively successful (as in South Korea) a significant increase in the volume and intensity of data being gathered from individuals. Using data gathered from existing sources including mobile phone use, card payments and social media access, the Chinese authorities were able to track the movements of those who visited the market in Wuhan at the pandemic’s centre. Data on smart bracelets and watches, providing the information on the resting and waking heartrates of 115,000 people in nearby Anhui province has been additionally used to help build a machine learning forecasting model for future COVID-19 outbreaks.

Other expansions of biosecurity technologies are less widely-debated, but also imply a significant expansion of monitoring and data collection: Amazon has introduced infra-red sensors in some of its warehouses to monitor staff temperatures and proximity, whilst temperature checks for commuters are being considered by the UK government. With the boundary between work and home becoming blurred (or even “obliterated”) under lockdown, workplace surveillance has crept further into private houses. Meanwhile, US-based Draganfly have trialled their “pandemic drones” in Connecticut, which aim to “detect COVID-19 symptoms and monitor social distancing”.

Loss of public value

Much of the public debate around this has centred on the implications for privacy, and the lack of transparency about the use being made of data – particularly health data – by firms operating under government contracts. US data specialist Palantir has attracted particular controversy for its work on NHS data, recently extended by the Department of Health. This work has involved cleaning and organising NHS datasets for use in future machine learning and other data-based healthcare technology; although Palantir itself was initially paid a peppercorn fee for the work, the future value of data prepared for further processing is enormous.

And it is the loss of potential public value, and the lack of scrutiny over the use of public datasets, that should also concern us here. COVID-19 has disrupted entire sectors: aviation, hospitality, and entertainment are likely to never be the same. For a period in May, shares in teleconferencer Zoom were worth more than the world’s seven largest airlines added together. But whilst there are a few new entrants into the expanded digital economy, the overwhelming beneficiaries have been the existing entrants.

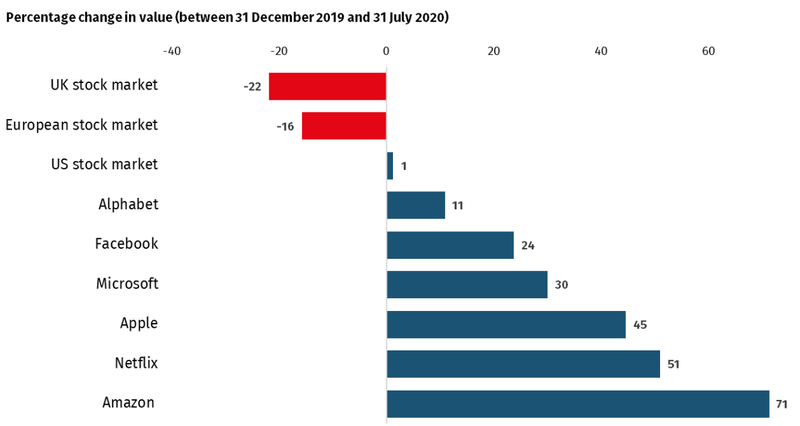

New figures from the IPPR show that the stocks of six US digital giants have risen in value by $1.9 trillion, or 38%, since the start of the pandemic. This increase in their valuation reflects both the current dominance of Big Tech, and (not unrealistic) market expectations of continued expansion.

The value of six Big Tech firms has grown by between 11% and 71% since the pandemic began

Even the immediate economic fall-out from the imposition of social distancing – primarily, the collapse in demand across the globe – is hardly likely to affect the dominance of the major tech platforms. In the short run, the combination of falling demand and rising debts is particularly concerning. The risk for economies across the globe is in hitting the vicious circle that appears when falling demand results in falling incomes and falling prices. Because debt and debt repayments are made in money, but (with falling prices and incomes) less money is available to those who have to repay debts, the relative burden of the debt is increased. As more and more of what little money is available has to go to servicing debts, demand in the rest of the economy is further reduced. This vicious circle is called debt deflation and for those firms and households on the wrong side of the deflationary process – carrying too much debt for too little income – it can be devastating. In the short- to medium-term, it is the biggest single danger for most of the economy.

Most, but not all. While the first phase of the crisis has seen a rapid expansion of (already high) non-financial corporate debt across the globe, as companies felt the impact of collapsing revenues, the major tech companies entered the crisis with rock-solid balance sheets, sitting (in effect) on immense piles of cash. They are therefore ideally positioned, as the Telegraph has noted, to further increase their market dominance in the event of significant bankruptcies elsewhere – including sideways moves into new and adjacent sectors, like Amazon opening high street stores.

But these are only the relatively short-term impacts of the crisis, and they could in principle be dealt with (for example) by tighter competition law and changes to corporate taxation. At least on the latter, the international pressure for taxes specifically designed to capture at least some of the economic rents generated by the tech giants’ new business model is growing. But these are presently falling victim to the general disintegration of international economic co-operation, increasingly obvious over the last decade, with the US pushing back hard against France’s proposed tax on digital revenues, the UK’s Digital Services Tax, and pulling out of the OECD’s discussions on a global multinational tax framework, claiming they were at an “impasse” and threatening retaliation against measures that taxed US digital companies.

Strategic considerations by state

his draws attention to the final part of the dominance of Big Tech in the pandemic economy – again, a continuation of a preceding tendency – which is its presence in increasingly strategic behaviour by states to support the tech companies resident in their territories, and the increasingly aggressive – often non- or anti-market – methods through which they are competing with each other globally. The ongoing trade dispute between China and the US is, at heart, a dispute over the development, control and use of digital technology.

China has its domestic digital giants, like payments giant Alibaba (itself responding rapidly to the crisis), and national champions like Huawei – officially designated as such since 1996, and which owes its technological edge, in no small part, to the support of the Chinese state, amounting to perhaps $75bn of subsidies. Aggressive moves to exclude Huawei from global markets, conducted through the guise of national security concerns, have more to do with fears by the US and its tech companies of losing significant future market share to its upcoming rivals.

Britain’s flip-flopping on Huawei’s presence in new communications infrastructure – supporting it (with restrictions) in January, opposing it (with a delay) in June – is driven by US strategic concerns: there has been no meaningful shift in the apparent security risks attached to Huawei, and in any case the UK has a specific security expertise for the company through the Huawei Cybersecurity Evaluation Centre, in operation at Banbury, Oxfordshire since 2010. At present, however, Huawei holds the dominant technological provision in 5G infrastructure, being able to supply the essential equipment more cheaply than its nearest rivals (principally Nokia, Ericsson, and Samsung) and (importantly for countries with more robust planning regimes, like the UK) able to do so with fewer aerials, allowing for speedier deployment. Not using Huawei represents a genuine economic cost in this sense.

5G, once implemented everywhere, would represent a step-change in the presence of the internet in our daily lives. It would allow the creation of a genuinely ubiquitous “Internet of Things”, continuously connecting any given device to the global internet. This, in theory, could bring applications like remote surgery or self-driving cars much closer to reality, but as a result, the number of connected devices globally is forecast to rise from 15 billion today to 75 billion in 2025, generating 90 trillion gigabytes of data annually – up from 66 trillion gigabytes produced by the entire internet in 2018. The failure to capture the market for the provision of its infrastructure is a serious blow for the US, which has lost its technological lead in telecoms equipment over the last two decades. The longer-term fear for Washington is that a country achieving a fully-blown 5G implementation first would be able to leverage that increase in data into an insurmountable advantage in data-intensive new Artificial Intelligence applications.

In the meantime, expansions in data generation and transmission are predictably likely to favour the Big Data incumbents, who can use their existing economies of scale in the processing and analysis of data to further dominate new markets. Already, Alphabet, Google’s parent company, signed a deal in March with US telecoms provider AT&T to provide clouds services over 5G, whilst Amazon announced a similar 5G partnership with another US telecoms giant, Verizon, in December last year.

The digital commons: local and regional action at the forefront

One response to this market domination is to argue for greater competition – to break up the digital giants, and to impose regulations (as far as possible) on their activities. But there are two problems here: first, the capacity of the British state to take action against predominantly US multinationals is limited, particularly in the context of Brexit negotiations where the UK is not in the strongest position, as squabbling over the Digital Service Tax indicates. The IPPR report strongly recommends that data sovereignty needs to be reasserted by the UK in any future trade deals, and that underpricing the value of national datasets, like that of the NHS, perhaps to try and squeeze more favourable treatment elsewhere, will cost us severely in the long run.

Second, the data giants command the position they do because of the economies of scale in data: each new dataset, if added to existing data and processed, generates more value. This is potentially a real gain for society; breaking up those economies of scale through imposing competition risks losing the gain from amalgamation. Worse, the creation of many competing smaller companies risks simply reproducing the undesirable activities of the existing companies many times over.

Instead, IPPR’s new report proposes that we work towards creating a digital commons: that we recognise the value of data and its processing exists in its aggregation, but that we can seek to create new forms of ownership for that data that allow the value to be put to public use. Data trusts are one promising mechanism to do this, potentially allowing (for example) local NHS providers to exercise greater control over their patients’ data without losing the value-added of aggregation. The question of scale can be addressed directly – already cities like Amsterdam and Barcelona are using their city-wide powers (through regulation and procurement, principally) to place the value created in the city’s data back into public hands and under democratic control. Local authorities and Metro Mayors in the UK have fewer direct powers, but licensing and regulation, as well as procurement – if conducted on a multi-authority basis – can both be used creatively, as the report argues.

Combined with the need, which is becoming all too apparent as the COVID pandemic moves into its next phase, of tailored, local responses to outbreak and the management of social distancing, local authorities should be seeking ways to bring the management and use of data in their areas of governance more directly under transparent and democratic control. As has become clear over the last few months, national measures must be retained, including the rapid use of national lockdowns where a situation has run out of control. But in practice localised flare-ups of this virus will require localised measures, and management of social situations when the virus is known to be present will require tailoring. The point has been stressed repeatedly by public health experts that the centralisation of public health provision in Public Health England, arising from the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, alongside severe cuts to local authority funding left the UK poorly prepared for a pandemic of this type.

Meanwhile, the perceived failure of the national Test and Trace system has led to one council setting up its own, local version of the same. This is not a digital operation, in the first instance: effective contact tracing, as the evidence from South Korea and elsewhere shows, needs human contact tracers able to interview and record accurately the different social contacts those infected (or in contact with those infected) have made. It is only after this contact has been made that data technologies can come into their own. Contact tracing apps, despite the fuss made over their possible use, have been effective only when supplemented by heavy use of human contact tracing, and concerns about personal privacy and possible data-grabbing by their operators have been raised across the globe.

Dealing with the particular challenge of excessive reliance on digital technologies, ironically, may also require other councils to implement similar local contact tracing systems, rather than relying on the national rollout. New powers for local authorities to deal with local outbreaks, announced in July, make viable local tracing more important – particularly if, as Sandwell council claim, the data needed to contain local outbreaks is not forthcoming from national government. It is not entirely clear that the new Joint Biosecurity Centre, intended to be the first national contact point for local information on cases and co-ordinator of the national response, is entirely up to speed. Announced in May, it was meant to be fully functional “later in the summer” to provide national guidance on alert levels, but has suffered from being “shrouded in secrecy”, in the words of one SAGE member. In the interim, local and Combined Authorities should be looking at their own data use during the pandemic, with a view to applying it on a local and regional basis.

But the challenges of COVID-19 are not only in the immediate and near future. The pandemic is imposing longer-term changes: with or without a working vaccine, speedily developed, produced, and deployed, at least some of the shift in working patterns and social life, in particular, is likely to prove permanent as we adjust to a world in which the risks of future outbreaks are both more likely and seen to be more likely. These shifts will, as we have seen, almost certainly involve the greater penetration of data technologies into every part of our lives. Local and regional plans for the recovery need to start building in their own plans for local and regional data use and processing in the years ahead, as an integral part of their post-pandemic planning – for example, in creating locally- and regionally-owned and managed Smart Grids, which are hugely data-intensive and which the data giants are investing in.

Looking further out, we need to place the national regulation of data on a different setting: not one based only on competition – although anti-monopoly action has its place – but on the broader concept of a digital commons. As the IPPR report recommends, a new Office for the Digital Commons could and should be created from the existing regulators, charged with exactly this overview.

Be the first to comment