What sort of future do you want for yourself and your children? If it’s not more of the same, then it’s time for some radical thinking.

GIMMS is the Gower Initiative for Modern Monetary Studies

Cross-posted from GIMMS MMT Lens

Three common neoliberal threads run through this week’s news: How will the enormous sums of money borrowed by the government to hold up the Covid-19 ailing economy be paid for? How can we fix the crisis in social care which has been starkly revealed over the last few months? And the continual covert shifting of responsibility from government to the public in the endless blame game which has created the narrative that poverty and inequality is a personal failure that bears no relationship to government policy.

Over several weeks now, and already noted by the GIMMS MMT Lens in previous blogs, the narrative of getting the public accounts back into balance has been a constant theme in the media; preparing us for the worst, preparing us for the inevitable. Revenue raising, public sector pay restraint and finding savings, returning to normal levels of ‘borrowing’, not to mention talk of plans to balance the books.

After 10 years of austerity and the very visible consequences which are wracking society, combined with the economic effects of Covid-19, the public should be shaking in its boots at such talk. Yet there is often a veiled acceptance that there will be no alternative. Only this week, Douglas Fraser in an article which appeared on the BBC website entitled ‘Is it time to rethink the tax system?’ repeated the common tropes that more tax revenue would be needed to fund government borrowing and the enhanced public services the nation is demanding. Quoting the Public Accounts Committee on the subject of tax breaks, it was suggested that they cost the public purse hundreds and billions of pounds in lost income as if somehow the government was a public limited company, a local government authority or indeed you or I.

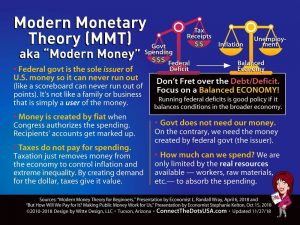

Forgive us if we keep labouring the point, but wherever you look you just can’t get away from the false Household Budget version of the public money system – it pervades the public consciousness like a bad penny. Both on the left and right it informs every comment by journalists, politicians, government institutions and think tanks. From the wealth taxes to pay for public services suggested by the Shadow Chancellor Anneliese Dodds, to the price the nation will have to pay for all that additional spending. Never mind that its aim was to keep people from going hungry and being unable to pay their bills when the economy was going into a nosedive because of lockdown.

One might, of course, take issue with the way this fiscal programme was carried out, benefiting as it did businesses and corporations rather than working people directly, with the fact that many were let down by a welfare system which had already been proved not fit for purpose with many falling through the cracks, not to mention the vast sums of money poured into public contracts with the private sector. But such a fiscal injection was vital and will continue to be vital for many months to come, even as the furlough scheme is closed and we face the prospect of a huge rise in unemployment on levels not seen for many decades. These were political choices unrelated to monetary realities and we would do well to recognise and emphasise that fact when talking about how money works.

Even whilst the conversation is about how it will be paid back and in an age where national sovereignty has been deliberately ceded to global corporations, it demonstrates with stark clarity the real powers of a government which has sovereign currency-issuing powers to act quickly and with public purpose (should it choose to do so) without reference to the state of the public accounts (as was already patently clear from the bank bailouts in 2008 but which somehow we seem to have forgotten!)

In the review of a recently published book ‘Post Democracy – after the Crises’ authored by the academic Colin Crouch it notes that:

Globalisation having curtailed the ability of national governments to shape economic policy, the neoliberal ideology that drove it “has turned this weakening of the nation-state into a virtue”. For Crouch, neoliberals view governments as “almost by definition incompetent” and sought to strengthen the power of multinationals as more dynamic, efficient stewards of economic well-being. But neoliberalism was never about simply weakening the state –instead, it requires continual state intervention to create and shepherd market mechanisms, as well as obligatory bailouts and subsidies (as we see in the current crisis). The anti-statist rhetoric of neoliberal populism bears little resemblance to the actual practice of neoliberals in government.

Whilst denying modern monetary reality (even though that is what it has been doing in effect) the UK government has not had any financial problem dealing with the current crisis – funding its agenda or lining the pockets of the corporate beneficiaries who no doubt will continue to profit from the public purse. Contrast that with the false narrative being pursued about affordability and how it will be paid for ultimately and surely the contradictions are staring the public in the painfully in the face, particularly now.

Instead of examining this from the point of view of how public purpose can be served through government action, the myths and legends of how governments spend are being shamefully repeated to reinforce the desired message that it will have to be paid for. This strengthens the intrinsic public belief that our public and social infrastructure will have to bear the brunt in the end.

Many will approve of the government’s stated intention to create thousands of UK public sector jobs – from nurses to teachers and police officers – after years of unnecessary cuts which have damaged our public and social infrastructure. But seen alongside the narratives of rising ‘government debt’ and questions about how it can be paid for, they will understandably mistrust the government’s expressed intention, whether that’s rebuilding an already decimated public sector or levelling up society. Especially those who understand that cutting departmental budgets to find so-called savings which can then supposedly be spent elsewhere is a fantasy and a deception.

For many decades, the question of funding social care has been a reoccurring theme in political circles and this week it was brought yet again into public focus as it was revealed that the government was considering plans for over 40s to pay more tax or national insurance or self-insure to contribute towards the cost of care in later life either at home or to cover the cost of a stay in a care home. It would, in the words of the Conservative MP Damien Green, resolve the funding question, whilst the Liberal Democrat former MP Paul Burstow suggested that it would put ‘social care on a firm footing for the future … to ensure sufficient funds are raised’. The chief executive of NHS England, Simon Stevens, said in an interview in early July that he hoped that ‘by the time we are sitting down this time next year, on the 73rd birthday of the NHS we have actually as a country been able to decisively answer the question [of] how we are going to fund and provide high-quality care for my parents’ generation’.

That sticky, sticky question of how we will pay for it yet again raises its ugly head and yet again fails to acknowledge monetary realities. Aside from the facts that the flat-rate tax being suggested would be regressive and inequitable punishing those on already low incomes and that it would take income that would have been spent into the economy out of the economy at a time when it is already struggling (and will be likely to do so for some time yet, maybe even years), it does not represent the reality that such a tax does not equate to a pot of money put aside by government to pay for anything – let alone social care.

As Alan Greenspan said in response to a question by US Congressman Paul Ryan about personal retirement accounts helping to achieve solvency for the system.

“Well, I wouldn’t say that the pay-as-you-go benefits are insecure, in the sense that there’s nothing to prevent the federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to somebody. The question is, how do you set up a system which assures that the real assets are created which those benefits are employed to purchase.”

The UK is no different. Importantly as Greenspan points out and which equally applies, although in a different context here, it could create the money to fund social care tomorrow, if it chose. The real constraints would be assuring that government had made provision to ensure that the real assets are available – in this case sufficient care workers with good pay and conditions and an adequate care home infrastructure to deliver high-quality care.

That requires both planning and political will and, for the best outcome, restoration of social care to the public sphere rather than being run by corporations who are intent on cutting costs for profit. The endless round of austerity has cut funding to local authorities charged with social care provision, combined with its provision through the private sector has been damaging. This and the colossal failure of care revealed due to Covid-19 show that it is time for a radical rethink about social care provision.

We need to stop thinking about how it can be paid for because with modern monetary realities in mind that is a given. Instead, we must start thinking about how we can create a decent social care system which offers dignity to those who need its services and fair pay and conditions for those providing them.

Finally, in this week’s news, there has been another frequent constant theme – blaming the populace for government failings. Whether it’s Matt Hancock blaming the public for the rise in coronavirus infections (notwithstanding the complete dog’s dinner that has been the constant theme of this government’s handling of the pandemic with its tardy and inconsistent communication and messaging), telling us we can save the NHS by cycling and losing weight (implying that you’ll be to blame if the NHS sinks beneath the waves) or the shocking comments by Jacob Rees Mogg’s sister Annunziata who tweeted that people on low incomes should buy fresh produce instead of junk food to save money and learn to budget and cook to improve their health. Rees-Mogg, speaking from her ivory tower of wealth and privilege, clearly has no idea about the lives and struggles of ordinary working people. Instead let’s blame, blame, blame.

The neoliberal notion of personal responsibility has become paramount in government messaging down the decades. One which has disputed the role of the state in creating a positive vision of society which puts collective action at the heart of government policies.

We all have a role to play as part of any collective action to improve the nation’s well-being, but such messaging is less to do with collective action and more to do with shifting the blame downwards so that government is no longer in the firing line and can thus abdicate its responsibility and deny democratic accountability.

It is time to acknowledge the government’s responsibility for the socio-economic conditions people find themselves in. Not just the consequences of austerity – the cuts to public sector spending on our NHS, social care, education, policing and local government – but also those policies which have decried full employment as a policy objective and left people in low paying, precarious employment with less protection against the ravages of capitalism. It is time to recognise the socio-determinants of the nation’s health and how governments have used the blame game to shift attention away from their real objectives. Serving not citizens, but global corporations and shovelling public money into private profit. Westminster Plc!

If the government can create money on a whim to fund its friends, then equally it can create money for the public purpose and to pursue full employment. Don’t let anyone tell you that it can’t. Learn the real story about money and what the very real constraints to spending are and how the government’s role is to balance the economy, not the budget. Our lives will depend upon it.

Be the first to comment