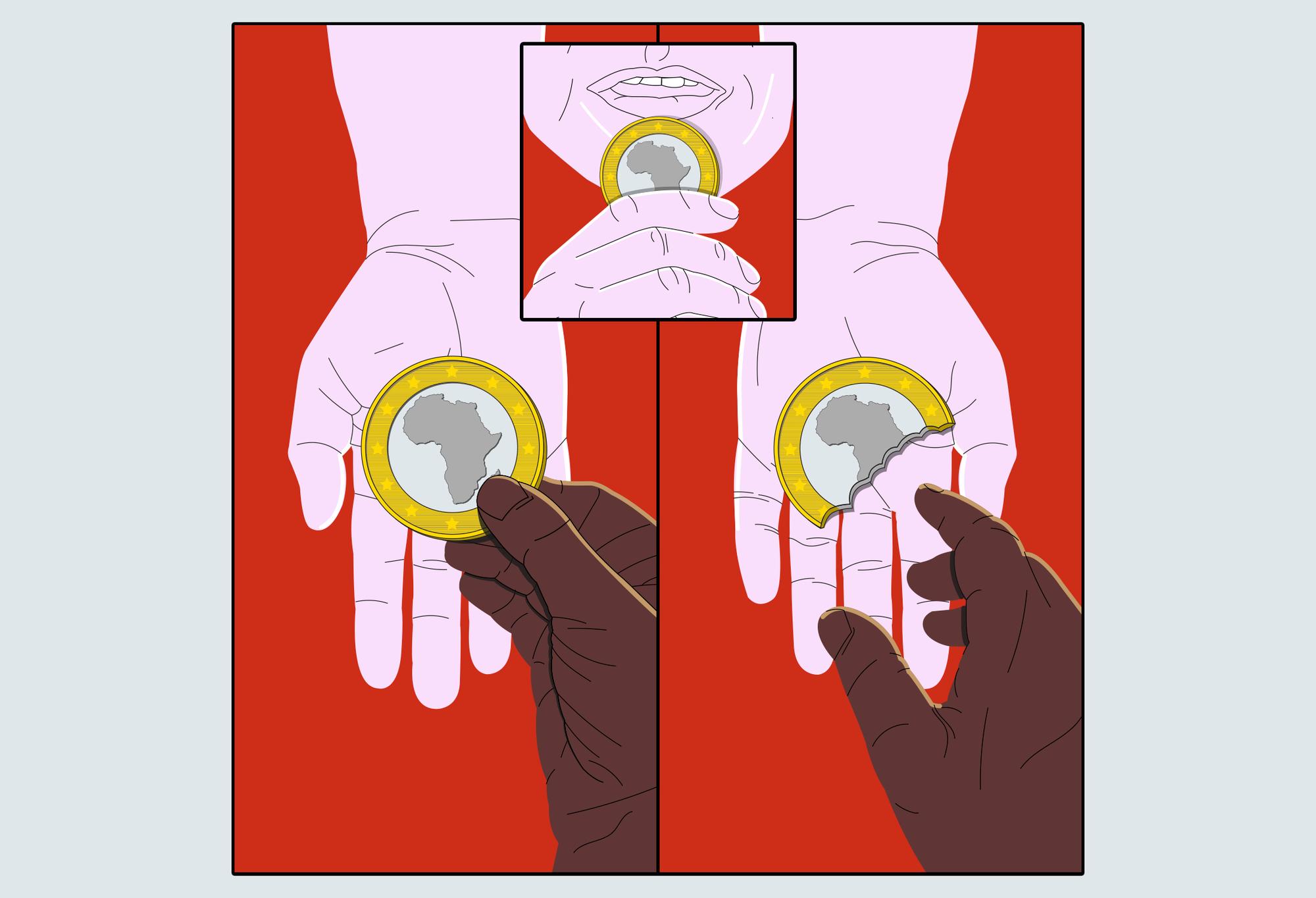

Several African countries depend on remittances sent by family members working in Europe or the US, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic. However, sending remittances to Africa has the highest cost in the world and transfers to cover basic needs have become a business managed by two large companies: Western Union and MoneyGram, who use high commissions and exclusivity clauses to keep their profits intact.

Jaume Portell Caño is a freelance journalist specialised in economy and international relations, always in relation with the African continent. In 2018 he won the 10th Casa Africa Essay Award for “Un grano de cacao”, an analysis of the relations between Africa and the rest of the world through the chocolate industry, among other aspects.

Cross-posted from El Salto

At the end of March, nobody talked about anything else in Kolikunda. The inhabitants of this small village in the interior of The Gambia were building a road that provided work to practically all the inhabitants of the place. The infrastructure project had become the source of wealth for the places it passed through, once muddy roads of sand, with stones and slopes that made transport difficult. Before Kolikunda, it was the inhabitants of other places who built it, until the work was too far away and travelling longdistances ot work was no longer profitable.

Mulie Baldeh was in charge and received 250 dalasi per day worked (just over 4 euros), a higher salary than the rest of his colleagues. The conditions were harsh, but preferable to their previous occupations: selling donkeys, dogs or cutting down trees to market the wood to Chinese entrepreneurs. At six o’clock in the morning, dozens of men were going to the road to twelve-hour work days that were changing their lives.

Until then, many families in the village depended on the monthly remittance of a relative to survive, which created a gap with those who had no relatives working in Europe or the United States; thanks to the road construction, even those who did not have access to remittances were able to start building a house. The dream lasted until the arrival of the coronavirus that paralysed the road works. The regular income disappeared and the dependence on remittances became determinant again: Kolikunda’s children in Spain, Qatar, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy are once again the principal hope of the villagers.

Uma Jawo is one of those people. Jawo is 22 years old and lives in Catalonia with her mother and other relatives; the young woman has worked in the hotel industry, in factories and in construction, and considers that the remittances received over the years are what have allowed great changes at home: “My family have gone from eating only what they grew to being able to buy sacks of rice and oil. Food, clothing, shoes, school fees, and housing: life there is what it is thanks to remittances.

Some families live in houses made of straw and mud, better known as “sudo huro”; depending on the number of family members they have abroad, the passing of the years allows them to aspire to more solid constructions. “There are at least 15 people in each house, and the number can reach 35,” says Jawo, who is currently unemployed. The young woman confesses that the current situation generates a lot of pressure on immigrants: “What I send is to help my cousin’s family buy rice; they have run out and the situation will not change until I can send them something. People are completely dependent on what you send, and they can’t help but tell you that you have to get a job now. Tractors, electricity, and other tools that make work in the fields easier also depend on remittances.

The business of poverty

In 2018, 529 billion dollars reached developing countries, but those who gained the most from these remittances are not the likes of Jawo or her relatives in Kolikunda. In 2015, The Economist revealed that 80% of a Turkish entrepreneur’s business is based on migrants from low-income countries: his name is Hikmet Ersek and in 2019 he earned more than $10 million as CEO of Western Union.

The operation of the company is simple: thanks to an extensive network, anyone from anywhere in the world can send money to a family member or friend in exchange for a service fee. The Western Union brand is present throughout the continent, from large cities on the coast to the most remote areas of Africa.

According to the World Bank, sending remittances to Africa has the highest fees in the world, with an average of over 8% per transfer. Sources of remesas.org I consulted consider that several factors influence this situation: “They are more expensive because they are taxed – by local governments – and because companies use mechanisms that inhibit competition and generate artificial and illegitimate monopolies, which are much more costly for the consumer”. In Africa, two US companies share two-thirds of the market: Western Union and MoneyGram.

At remiesas.org they consider that remittances have become an easy source of income for governments and businesses, in collusion with local banks. The few banking licenses granted in many African countries make it easy to capture markets, and Western Union and MoneyGram take advantage of this to sign exclusivity clauses: any customer who wants to send or receive money must go through one of the two companies. “As a banker you make your network available to them at outrageous prices, because you get a percentage. You want the fees to be expensive because you get paid more,” they add, from the remittance company.

Exclusivity clauses create de facto monopolies, which push commissions up to 15 or 20%, above the figure of 8% of the official rates. The source for this article dedicated to remittances considers that the World Bank model has little to do with reality, by analysing the money sent as a fixed amount, when in reality the sum paid out to the recipient is rarely the same amount.

Who pays?

The Gambia is the smallest country in Africa and has a particular situation that is very detrimental to migrants and their families. Apart from the commissions charged by the intermediary companies, the country’s central bank is using an exchange rate that is very harmful to Gambians in order to obtain income.

In October 2019, Jawo sent 250 euros to a relative through Moneygram. The company’s 6 euro commission made the final figure sent 244. On the day he sent her money, one euro was equivalent to 56.5 dalasis, the Gambian currency. Her relative should have received 13,786 dalasis, but in the end he had to settle for 12,281. The exchange rate applied meant that her relative received 50.3 dalasis for every euro.

The figure of 6 dalasis per euro may seem insignificant, but the higher the number of euros sent, the greater the loss to the recipient. On that day, Jawo and his relative lost EUR 6 for the fees and EUR 26 for the exchange rate. Of the 250 euros sent, 32 were lost along the way, almost 13% of the initial figure. Outrageous comparison: 32 euros, at today’s exchange rate, is what Mulie Baldeh would earn in a week working twelve hours a day building a road.

In 2014, a report by the Overseas Development Institute, a British think tank, showed that remittance surcharges linked to the market control of Western Union and MoneyGram deprived the continent of an extra $586 million a year. And they believed that a drop in fees would allow money transfers to increase by $1.8 billion. In other words, the cost of primary education for 14 million people, improved health care for 8 million, or clean water for 21 million.

The weight of remittances in GDP is around 10% in several African countries: in Zimbabwe (13.5%), Senegal (10.5%), Liberia (9.4%), The Gambia (15.5%) and Lesotho (21.3%), thousands of people pass through Western Union or MoneyGram offices every month to collect most of their income. In Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, remittances account for almost $24 billion a year.

Remittances also have another advantage for the corporations who benefit from them: they are constant and, as the years go by, they increase. Development aid changes according to the budgets of the donor countries, financial capital moves according to the international situation, as does Foreign Direct Investment; but family members will never stop sending money to their loved ones. In 1990, remittances were at the bottom of the ranking; in 2019, the IMF ranked them above these other three sources of income. Right now, the largest international aid for Africans is the small amounts that their own relatives regularly send them from rich countries.

The Competitors

Giants like Russia and India have successfully challenged these de facto monopolies. A report explains how in 2001 a Russian money transfer company, after its initial success, saw a number of banks cancel their partnership agreements by referring to an exclusive contract they had signed with Western Union. The situation ended in a protest to the Russian ministry in charge of regulating competition, which found in favour of the Russian company. Western Union appealed to a Russian court, but lost and had to pay the costs of the trial. Since then, Russia has been the G20 country with the lowest commissions, with an average fee of less than 2%.

In Africa, countries such as Nigeria and Ethiopia have declared exclusivity clauses illegal; Senegal has approved measures to combat the situation, although in Cameroon or Gabon these agreements are still in force. In the documentation it sends annually to the SEC, the United States financial control agency, Western Union considers that these legal changes could be detrimental to them, to the extent that they could “adversely affect our business, our financial conditions and the results of our operations”.

In addition to the $25 million earned by its management team in 2019, Western Union delivered $880 million to its shareholders in dividends and share repurchases. CEO Hikmet Ersek announces in his note to investors that the dividend for the last quarter of the year increased by 13%. The six major shareholders are investment funds located in the United States and the United Kingdom. Between them, Blackrock (13%) and Vanguard (12%) hold a quarter of the company’s shares. Other owners include Goldman Sachs, Credit Suisse, JP Morgan, Wells Fargo and Deutsche Bank.

In MoneyGram, with less buoyant figures, there are more investment funds involved – with Blackrock and Vanguard present again – and the bank Morgan Stanley. More comparisons: the value of Blackrock and Vanguard shares in Western Union outweighs the Gambian GDP. In other words, economically speaking, a quarter of a company with 11,500 employees is worth more than a country of more than two million people.

The Future

Guinea-Bissau economist Carlos Lopes, the African Union’s high representative for negotiations with Europe, believes that the only option for Africans is to unite: “This business will be domesticated by bringing together the interests of all of Africa. Just as we can agree on a large continental free trade area, we should be able to draw up a set of principles that will then be applied throughout the continent.

Beyond a coordinated policy, Lopes believes that there is already reason for hope with some initiatives that the continent is experiencing: “Competition is coming through the expansion of mobile banking. An important part of remittances are between African countries and the expansion of cross-border banking operations in the continent will reduce the need for businesses that only transfer money,” he concludes.

Western Union, despite being immersed in litigation around the world for its monopolistic practices, is close to its historical high on the stock market. Since the 2008 financial crisis, MoneyGram’s stock has plummeted. The latest attempt to revive it, in 2017, came with an offer from a Chinese company linked to Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba. AntFinancial, which specializes in financial services, made an offer to buy it at a price of $18 per share. The Trump administration blocked the operation for national security reasons, and the shares fell again.

As in the conferences of the end of the 19th century, in power struggles major decisions are made at international conferences, but there is no chair is for the African people. There is no need to justify oneself, either to them or to anyone else, in order to extract income from the salaries of thousands of waste collectors, hotel maids, farmers, handymen or warehouse workers around the world. Neither Xi Jinping, the president of China, nor Hikmet Ersek, the CEO of Western Union, nor Donald Trump, the president of the United States, will ever drive on the dusty roads leading to Kolikunda.

Be the first to comment