China has established itself as a fully blown competitor to the IMF and World Bank for infrastructure investment worldwide, and in many places has usurped Western lenders.

John P. Ruehl is an Australian-American journalist living in Washington, D.C. He is a contributing editor to Strategic Policy and a contributor to several other foreign affairs publications. He is currently finishing a book on Russia.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

In October 2023, amid celebrations commemorating the 10th anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Beijing, Pakistan and Chinese leaders signed a multibillion-dollar deal for a railway project. As a pivotal component of China’s efforts to promote economic integration and develop infrastructure abroad, Pakistan has received significant developmental assistance from Beijing through the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Nevertheless, Western nations and financial entities have also been strategically maneuvering in Asia, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approving a $3 billion loan for Pakistan in July, “saving it from defaulting on debt.” Other countries in the region are experiencing similar competition. Bangladesh, for instance, inaugurated the BRI-linked Padma Bridge Rail Link in October, and weeks later received a $395 million loan from the EU. That month, Sri Lanka struck a debt deal with China, while the U.S. extended a $553 million loan for port construction in Colombo in early November.

As competition over infrastructure and investment has grown in recent years, standoffs between Western and Chinese lenders over debt restructuring and relief have intensified. Lenders hesitate to offer relief packages, fearing that one creditor’s concession might allow a debtor country to use that relief money to pay off others. These impasses underscore the challenges being faced by the decades-old Western-dominated financial system and lending initiatives.

The foundation of this system was laid at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944. The meeting established the IMF to ensure stability of the international monetary system and offer policy advice and financial assistance to countries in economic crisis. It has since grown and comprises 190 member states, while its “sister organization,” the World Bank, was created simultaneously and has grown to include 189 member countries. The World Bank focuses more on long-term assistance through loans and grants, supporting infrastructure and poverty reduction in developing countries.

Efforts to democratize these institutions have been made, but both the IMF and World Bank still remain under significant Western influence. Western countries are overrepresented on the IMF’s boardand voting arrangements, while all the IMF’s managing directors have been European. All the World Bank’s presidents except for Bulgarian national Kristalina Georgieva, who served as acting president in 2019, have been U.S. citizens, and the voting shares of the bank have not been rearranged since 2010. Both institutions are based in Washington, D.C.

In addition to the IMF and World Bank, other Western-dominated (or heavily influenced) multilateral development banks and institutions include the Paris Club, the European Investment Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the Asian Development Bank. Government initiatives like USAID, the U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, as well as private banks, also play prominent roles in advancing Western economic interests.

China’s role in multilateral banks like the IMF and World Bank has expanded as its economy has grown. But Beijing continues to criticize the current global debt governance system as “dominated by the ‘Paris Club-IMF-World Bank’ structure of the West,” and has chosen to create its own path to expand its economic influence globally.

China’s state capitalism offers a unique alternative to Western infrastructure and development initiatives for the first time in decades. Through its robust, globally integrated economy, technological expertise, and extensive industrial power, Beijing can help fund and build projects on a scale that rivals the West in a way not even the Soviet Union could achieve. Furthermore, Chinese assistance does not require political and economic reforms typically attached to Western developmental initiatives.

China’s approach has seen significant success. It has become the world’s largest creditor since 2017, and is lending more than the IMF, World Bank, and Paris Club combined, said Brent Neiman from the U.S. Department of the Treasury in September 2022. With $1 trillion spent and more than $2 trillion in contracts, China’s BRI has transformed global trade routes and economic development and is even garnering interest from the Taliban.

A Center for Global Development 2020 study estimated that Chinese loans generally have a 2 percent interest rate, in comparison to 1.54 percent for the World Bank’s concessional loans, and the penalties for late repayments have increased since 2018, according to AidData. Nonetheless, most BRI partner countries view China’s project positively.

To implement its vision, Beijing has deployed a network of national financial organizations, including the China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC), China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), China Development Bank (CDB), the Export-Import Bank of China, China Construction Bank (CCB), Silk Road Fund, China Investment Corporation (CIC), China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), and the People’s Bank of China.

Though China has largely focused on striking bilateral deals, it has developed some multilateral initiatives. The New Development Bank was created in 2015 and is headquartered in Shanghai. It is increasingly seen as a method to encourage transactions in China’s currency, the renminbi, between BRICS member states. Meanwhile, the Global Development and South-South Cooperation Fund (GDSSCF) is being used for China’s software-focused Global Development Initiative (GDI). But China’s major multilateral project is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which was established in 2016. Now with 106 approved members, the AIIB focuses on lending to investment projects, infrastructure, transport routes, energy, and information networks.

Other countries, including Western nations such as Germany, have some influence in the AIIB. Nonetheless, the bank is dominated by China. It has an effective veto over major decisions and has been governed by China’s former vice minister of the finance ministry, Jin Liqun, since its founding. China’s dominance prompted the AIIB’s Canadian communications chief, Bob Pickard, to resign in 2023.

A divided response by Western countries to China’s initiatives has further undermined their traditional dominance. Many expressed interest in the AIIB as it was being formed, and Washington failed to dissuade them from joining the bank. The U.S. then attempted to counter the AIIB with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which came into force in 2016. However, the U.S. left the organization in 2017 under former President Donald Trump, and the project was repackaged into a smaller one.

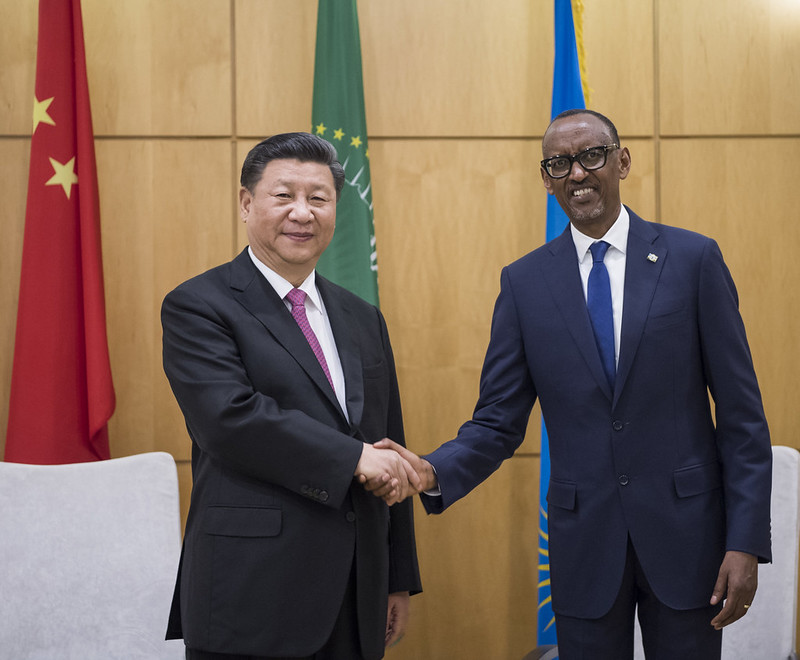

China’s newfound leverage has seen it confront the West around the world. In 1990, for example, Western countries accounted for 85 percent of infrastructure construction contracts in Africa. Yet from 2007-2020, Chinese entities provided $23 billion in funding for infrastructure projects across sub-Saharan Africa, more than double lent by banks in the U.S., Germany, Japan, and France combined, according to a study by the Center for Global Development. In 2020, Chinese entities were responsible for 31 percent of all infrastructure projects in Africa valued at more than $50 million, up from 12 percent in 2013, while the West’s contribution to the projects in Africa declined from 37 percent to 12 percent during the same period, according to the Economist.

Brazil and Mexico enjoy significant investment from China, and Argentina officially joined the BRI in 2022. In August 2023, China highlighted its increasingly important role in Argentina’s economy by providing a $3 billion loan that allowed the South American country to avoid default. Even in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, China has spent billions of dollars linking countries to the BRI.

Nevertheless, the U.S. and the collective West maintain considerable economic influence and have responded assertively. The U.S. passed the BUILD Act in 2018 and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) in 2022 to increase investment and infrastructure development in developing countries, and the EU put forth its Global Gateway program in 2021, “the bloc’s new infrastructure partnership plan that’s seen as an alternative to China’s worldwide Belt and Road Initiative.” Meanwhile, the World Bank’s lending to sub-Saharan African nations soared from $26 billion in 2019 to $49 billion in 2023, while the World Bank and the ADB also overtook Chinese entities during the COVID-19 pandemic to become Southeast Asia’s biggest sources of funding, said a report by the Lowy Institute.

The U.S. and the EU have also expressed support for developing a new transport corridor connecting India, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean Sea. Furthermore, the West has presented a united economic response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, including the World Bank halting all its programs in Russia. The AIIB’s $100 billion fund also still pales in comparison to the IMF’s $800 billion mobilization capacity.

Both the West’s and China’s economic lending and infrastructure practices, however, have faced criticism. Former Chief Economist at the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz, has stated that the conditions placed on borrowing countries by the World Bank and IMF often cause significant pain for local populations and stifle economic development in these nations. UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated in 2023 that the IMF and World Bank benefit richer countries at the expense of poorer ones, urging for change.

China’s projects have faced criticism for predominantly employing Chinese companies and workers, as opposed to making local hires, resulting in protests and attacks against them. BRI deals are also criticized for being opaque in terms of financing and implementation, and countries struggling to repay loans have found themselves giving up some autonomy to their export revenues. And while allegations of Chinese debt diplomacy are often exaggerated in Western media, Chinese economic opportunism has increased debt burdens and debt-for-equity swaps with BRI partners.

Pakistan’s multifaceted economic challenges persist despite its engagement with Western and Chinese lending and infrastructure institutions. The country is grappling with neighboring Afghanistan’s instability, its longstanding rivalry with India, the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, devastating flooding in 2022, systemic corruption, and soaring energy prices caused by the conflict in Ukraine.

While these challenges remain complex, investment stands out as a potential remedy. Rather than engaging in blind competition, a more effective use of funds for all parties involved could be achieved by acknowledging and pursuing greater coordination between Western and Chinese economic interests in the country, such as increasing Pakistan’s energy efficiency. Amid their competition, the AIIB and World Bank signed a framework for cooperation in common areas of interest in 2017, and the AIIB has similar agreements with the Asian Development Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

Despite the rise of alternative markets, China stands as the sole challenger to the West’s established lending and infrastructure development networks. This rivalry has already prompted slow reform in the decades-old financial system, offering support to emerging powers and impoverished nations. While more equitable economic statecraft may prove elusive, borrowing countries have an opportunity to leverage the best deals essential for their progress.

Be the first to comment