Global leaders will fail to address the climate crisis unless they confront its root cause: an unjust economic system that is killing the planet

Laurie Macfarlane is economics editor at openDemocracy, and a research associate at the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. He is the co-author of the critically acclaimed book ‘Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing’.

Cross-posted from Open Democracy

Next week more than 100 world leaders will descend on Glasgow for the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as COP26. The conference, which is the successor to the landmark Paris meeting of 2015, has been hailed as the most important climate summit in history. But whether the hype is justified very much depends on the course of action taken by leaders in the weeks ahead.

Under the terms of the 2015 Paris Agreement, countries pledged to reconvene every five years to agree more ambitious emissions-reductions targets that align with reaching net zero by the middle of the century. Setting targets is an important first step in the fight against climate breakdown, and it’s crucial that countries that have disproportionately contributed to the climate crisis lead by example. But if COP26 is to succeed, progress also needs to be made on how these targets are going to be achieved. It is in this area that the gap between politics and science remains perilously large.

One stark example of this came back in July when the British prime minister’s spokesperson for the COP26 climate summit, Allegra Stratton, suggested that the British public can tackle the climate crisis through “micro-steps” such as not rinsing dishes before putting them in the dishwasher.

Although her remarks were widely condemned, the idea that responsibility for tackling the climate crisis lies mostly with individuals who have to change their behaviour and make different consumption choices remains deeply ingrained. The internet is full of articles offering advice on how we can ‘save the planet’ by making small adjustments to our daily lives, even though many (but not all) of these will have a trivial impact on climate outcomes.

Of course, human activity does need to change if we are to avert climate catastrophe. The question is: whose behaviour needs to change, and whose responsibility is it to drive those changes?

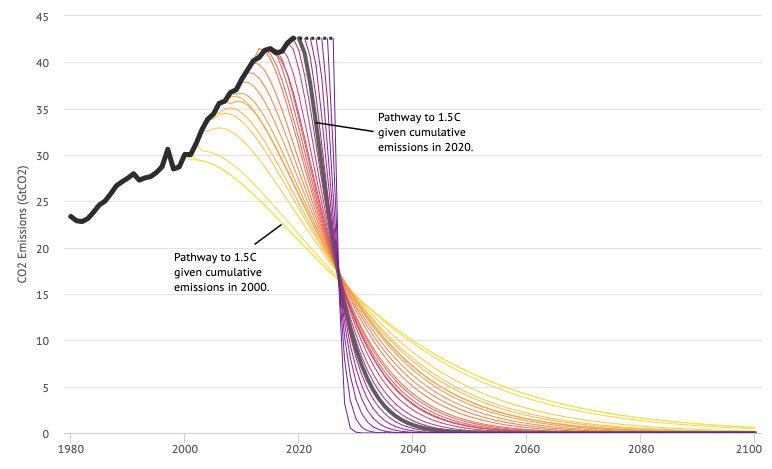

As the below chart shows, the task ahead is stark. If we had taken action to curb rising emissions in 2000, the pathway to net zero would have been relatively straightforward, and a gradual transition would have been feasible.

But delayed action means that emissions must now fall on a near-vertical trajectory. Each passing year of inaction produces a compounding effect, necessitating ever steeper carbon reductions in future years. According to a report published this week by the UN Environment Programme, countries’ current pledges would reduce carbon by only about 7.5% by 2030, far less than the 45% cut scientists say is needed to limit global temperature rises to 1.5°C. Unless radical action is taken, by the time the next major COP meeting comes around in 2026, the prospects for limiting warming to 1.5°C will have all but vanished.

Establishing what needs to be done requires an honest assessment of who – and what – is responsible for using up the planet’s carbon budget. Often this question is examined through a national lens: many point to the fact that China is now the world’s largest emitter as proof that Beijing is uniquely to blame.

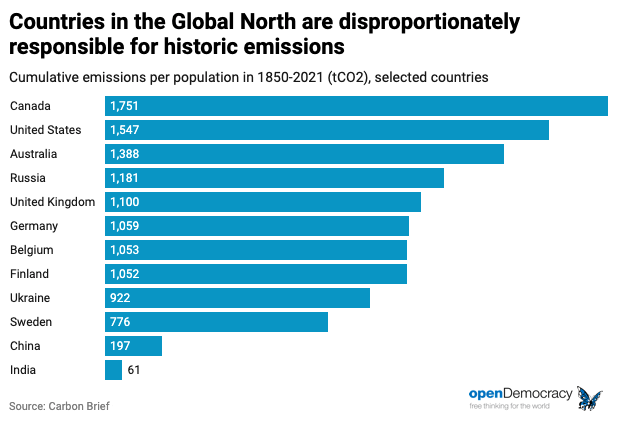

But in contrast to the advanced economies, China underwent industrialisation only in recent decades, and it accounts for over a sixth of the global population. When cumulative emissions over time are accounted for, and when the results are adjusted for population size, the results are starkly different. According to a recent analysis by Carbon Brief, the UK’s cumulative emissions per population is more than five times higher than that of China’s – and 18 times higher than India’s. While all countries must take swift action to reduce emissions, it is countries in the Global North that have played a disproportionate role in driving climate breakdown, and that are still enjoying the privileges of this position to this day.

Rich countries therefore have a moral obligation to lead by example at home, while also paying for a global just transition that acknowledges their historic responsibility for the crisis. But in the context of globalised capitalism that breeds inequality both within and between countries, looking at the climate crisis through a national lens is inadequate. Many countries in the Global North have ‘offshored’ their emissions by outsourcing manufacturing abroad, while many countries in the Global South are still suffering from the legacy of colonialism.

At the same time, within each country, not everyone is equally responsible for their country’s share of the world’s carbon budget. A 2020 report from Oxfam found that the richest 10% of the world’s population were responsible for 52% of the cumulative carbon emissions between 1990 and 2015. While the majority of these 630 million people represent the middle and upper classes in Europe and North America, they also include the very wealthiest people in China, Russia, the Middle East, and other countries. The per capita consumption footprints of this group are more than 30 times higher than that of the poorest 50% of the world’s population, while the footprint of the richest 1% is more than 100 times higher. To the extent that climate breakdown is a result of unsustainable consumption patterns, it is the consumption of the world’s rich minority that is the problem.

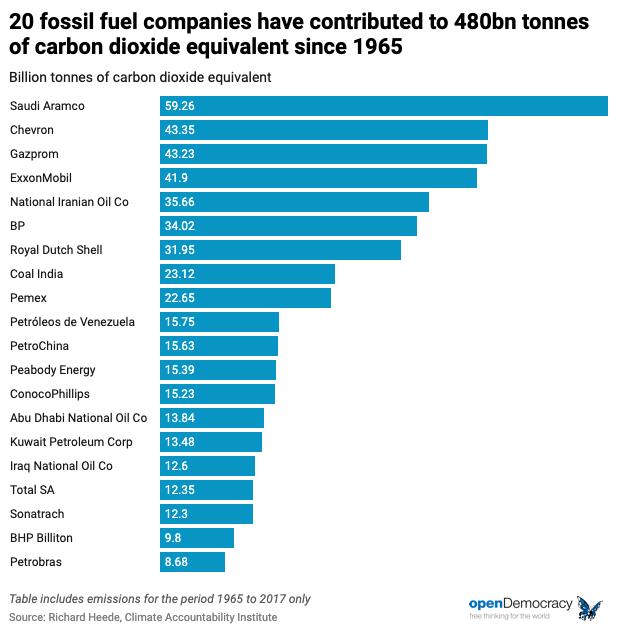

In addition, many of the world’s biggest polluters are not nation states, but multinational corporations. In 2019, a study from the Climate Accountability Institute found that just 20 fossil fuel companies have been responsible for 35% of all energy-related carbon dioxide and methane worldwide since 1965. For years many of these companies have sought to deliberately undermine the scientific consensus on climate change and downplay the risks in order to protect their profits.

More than anything else, the climate crisis is a product of excessive global inequality and unchecked corporate power. As a result, action on reducing emissions and delivering economic justice must go hand in hand.

Relying on businesses and individuals to take the lead on tackling the climate crisis will only lock us into our current trajectories. Instead, the solutions must be delivered ‘upstream’ – that is at the level of our economic systems. This requires systemic changes that will reduce everyone’s carbon footprint, whether or not individuals are willing to change their lifestyles, and whether or not businesses want to invest. The scale and pace of this transformation means that it must be state-led and coordinated at a global level.

Governments must rapidly implement plans for decarbonising their economies as fast as is equitably possible, and bringing their environmental footprint within fair and sustainable limits. This means delivering wholesale transformation of the energy, transport, housing and agriculture sectors, and rewiring production, distribution and consumption patterns across the entire economy. It means using every tool available – legislation, regulation, taxation, subsidies, public ownership, financial regulation – to re-write the rules of the global economy to serve different ends. And it means mobilising resources on a scale not seen since the Second World War. Crucially, rich countries must also provide substantial climate reparations to the Global South, but rather than burden nations that are already drowning in debt with more loans, these should take the form of unconditional grants, debt write-offs and technology transfers. As Keston Perry put it: “Reparations are not charity or aid, but an acknowledgment of responsibility by industrialised nations that they should pay their just dues.”

While it is vital that businesses across the economy are supported to invest in decarbonising their operations, we need to be clear that not all businesses can be part of the solution. There are parts of the current economic landscape that have no place in a zero-carbon world, which must therefore be dismantled. This should not be a controversial idea. Markets are not self-regulating forces beyond the realm of democratic control – they are outcomes that can be created, shaped and outlawed in line with social and environmental priorities. The decisions to abolish legal markets for slaves and child labour in countries like the UK were not made on the basis of some economic law, they were moral decisions. Today we need the same boldness from policymakers on everything from fossil fuel extraction and unsustainable agriculture to SUVs and private jets. The spectacle of countries like Australia, Saudi Arabia and the UK making net zero pledges while ramping up fossil fuel production makes a mockery of suffering that is already being endured.

The same goes for the rules that govern global trade, finance and intellectual property. Treaties that allow corporations to sue governments for taking action on cutting emissions that negatively impact their profits, and that protect the interests of international capital over sustainable development, must be abolished with immediate effect.

The climate crisis is not a distinct crisis – it is irrevocably linked to an unjust economic system that is killing the planet. Unless world leaders confront this head-on at COP26, a vital opportunity to put the planet on a sustainable path will be squandered. It will be those voices that are least represented in Glasgow that will suffer the most.

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge, please donate here.

Be the first to comment