Neo-liberalism has a face. In fact it has many faces. Lina Galvez looks at the career and egregious damage done to Spanish society by one of these faces: Rodrigo Rato.

Lina Gálvez is Professor of Economic History and Gender Studies at Pablo de Olavide University, Seville

Cross-posted from eldiario.es

Translated and edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

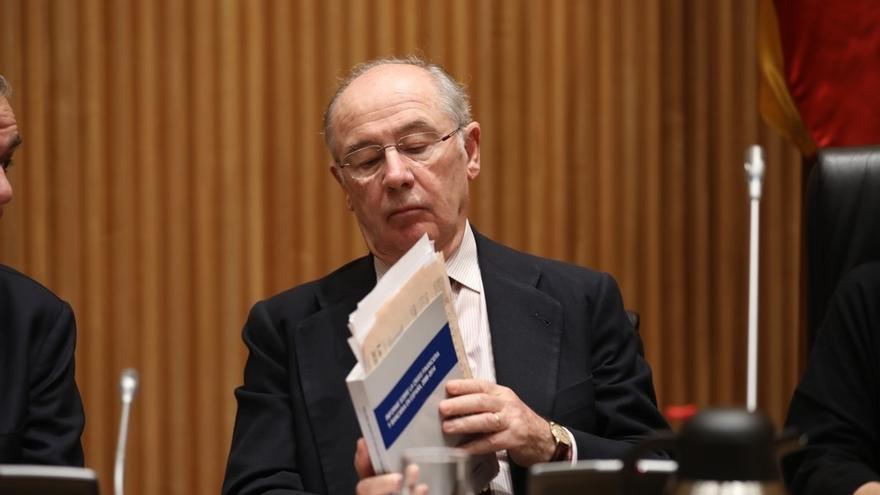

On January 9th of this year, Rodrigo Rato was the first witness to appear before the committee of the Congress of Deputies, the lower house of Spain’s parliament, which is charged with investigating the financial crisis, the bank bailout, and the bankruptcy of the savings banks. Its goal is to clarify the responsibilities and roles played by the governments of José María Aznar and Rodríguez Zapatero in precipitating and handling Spain’s economic crisis of 2008.

Mr Rato’s leading role in the economic crisis is spread between three significant positions he occupied: as economic vice-president of the Aznar governments (1996 and 2004); managing director of the IMF in the years preceding the outbreak of the crisis (2004-2007); and president of the Spanish bank Bankia. Bankia is the best example of the plundering of the Spanish savings banks, later becoming the greatest recipient of public money in the Spanish government’s bail-out of the banks.

Mr Rato is facing ongoing criminal proceedings in relation to all three crucial positions he had held. Those concerning his time as minister are not directed at his political management, but at his alleged money-laundering.

However, Mr Rato’s ministerial policy, and the fall-out from it, are worthy of study because of the economic, social and political model they represent and because of the sheer virulence of the economic crisis in Spain.

When I heard Mr Rato’s testimony my head was still full of the World Wealth and Income Database’s report on Global Inequality 2018, which has projections for income inequality and wealth until the year 2050.

In this brief report there are shocking graphs recording the growth of economic inequality in recent decades, and projections that predict, for example, growing polarisation and the possible disappearance of the middle class. The data on the brutal inequality that has developed in the U.S. since the 1980s, and the desperate plight of wide swathes of the American population, make their recent political behaviour much more easily understandable. But we can also learn a lot about Spain from this data.

In this report, Europe is generally portrayed as a single unit of analysis. Sometimes individual European countries are included according to the magnitude of the phenomenon discussed. Spain appears only with regard to a little-known indicator: the evolution of private wealth as opposed to public wealth. But this indicator is important in that it shows how loss of public wealth limits the ability of governments to reduce inequality, which undoubtedly has implications for altering the distribution of wealth among the Spanish population. Not surprisingly, the 100+ authors conclude that only greater public investment in education, health, and environmental protection would succeed in combating the growth in inequality up to 2050, which is projected in the report. Since the 1980s, however, there have been big changes in the distribution of wealth in all nations, except Norway. There has been a transfer of wealth from the public to the private sectors, to the extent that public wealth has become negative or close to zero in rich countries because of public debt relative to public assets. But although this is a global trend, there are some countries that stand out, such as Spain: in Spain the rise of this ruinous curve coincides with the arrival of the Popular Party to power in 1996, the introduction of the euro, and the start of the real estate bubble.

While testifying before the Parliamentary Committee the former minister boasted of his economic management skills, failing to mention the less flattering events of the past. The rules of the game were often changed by new laws, such as the Land Act, which permitted building on land previously excluded from development, which helps to explain a series of phenomena (the real estate bubble, the development of a speculative economy and an unequal economic model based on a labour market full of uncertainty, low wages, and low demand for qualifications). There was also a policy of privatising public companies, which had serious consequences for Spanish citizens.

It is true that the privatisations began with the government of Felipe González, but the crown jewels were privatised by José María Aznar. As I have analysed in the economic chapters of the book “Spain in Democracy 1975-2001”, between 1996 and 2004, coinciding with the two governments of Mr Aznar, with Mr Rato as economic vice-president, 60 companies were privatised for a value equivalent to 7% of the GDP.

Privatisations preceded the liberalisation of certain sectors, such as telecommunications and energy. As Spanish residents know, since they have to pay for the most expensive electricity in Europe, those privatisations did not bring higher levels of competition. Instead many monopolies were replaced by oligopolies intent on fixing prices and influencing governments to implement regulations that would further their interests. These companies had, and still have, boards of directors filled with retired politicians or “fresh” politicians through the so-called revolving door between business and government. These companies have gained market power detrimental to competition and consumer interests in key sectors.

In addition, Mr Aznar, Mr Rato and the Partido Popular put managers into these newly-privatised companies, in whom they had full political confidence. So many of these firms helped them to forge economic-ideological empires contrary to the interests of ordinary citizens. This process favoured a strong economic concentration – despite the fact that small- and medium-sized savers bought shares in these companies in imitation of British prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s popular capitalism. These past decades have seen the consolidation of extremely powerful economic groups very influential in politics, communication, culture and opinion-forming in Spain. They have championed a free-market mentality, inveighing against public management for resulting in higher costs, bureaucracy, and political corruption.

In addition, Brussels and Frankfurt allowed the Spanish government in the second half of the 1990s to include the revenues from its privatisations to disguise the deficit. This helped the process of fiscal consolidation, and apparent convergence with the Maastricht criteria, earning Spain entry into the euro club “on time”, without its economy actually converging with other members. The property and financial bubble was helped on its way by the arrival of cheap money from euro-zone surplus nations. These were the same nations which later demanded constitutional changes to guarantee the payment of the debt and the implementation of austerity measures that have suffocated the Spanish economy and worsened the living and working conditions of broad sections of the population.

So Mr Rato’s legacy is much greater and more troublesome than he himself has suggested during his court appearances. His legacy as economic vice-president of the Spanish government will be judged by history rather than the courts.

Be the first to comment