The ’European’ economy (if we can consider it as one regional unit) has been in serious trouble.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

Elections for the European Assembly or European Union (EU) parliament finish today. Citizens in 27 member states of the EU are voting for 720 members of the Assembly. Current opinion polls suggest that the two main ‘centrist’ groups of members (the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats and the centre-right European People’s Party) will lose more ground to those on the left or right of the centre; but particularly the so-called ‘hard right’ parties in the EU.

These right parties generally oppose immigration, further EU integration economically and politically, an end to ‘green’ policies and are reluctant to support the EU leaders’ foreign policy of backing the US and NATO over the war in Ukraine. The ‘hard right’ is split on many of these issues but they are still set to gain votes because of weak European economic expansion, particularly since the end of COVID pandemic slump, that has sent living standards down due to high price inflation, stagnant output and declining exports and investment.

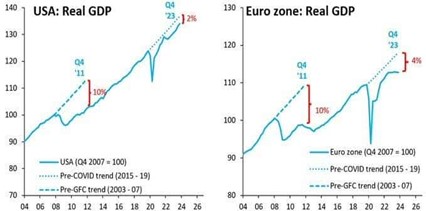

The ’European’ economy (if we can consider it as one regional unit) has been in serious trouble. After each global economic crisis (2008-9 Great Recession and the 2020 pandemic slump), the economy has struggled to recover, failing to return to its previous (weakening) trajectory of growth, worse compared to the US.

Indeed, the economic story for Europe since it formed its various political and economic entities (Common Market, European Union, Eurozone) has been one of relative decline in the 21st century. Back in the 1980s, Europe contributed 25% of world GDP, while growing at about 2% a year. In the 2020s, Europe’ share of world GDP had dropped to under 15% with growth barely 1% a year.

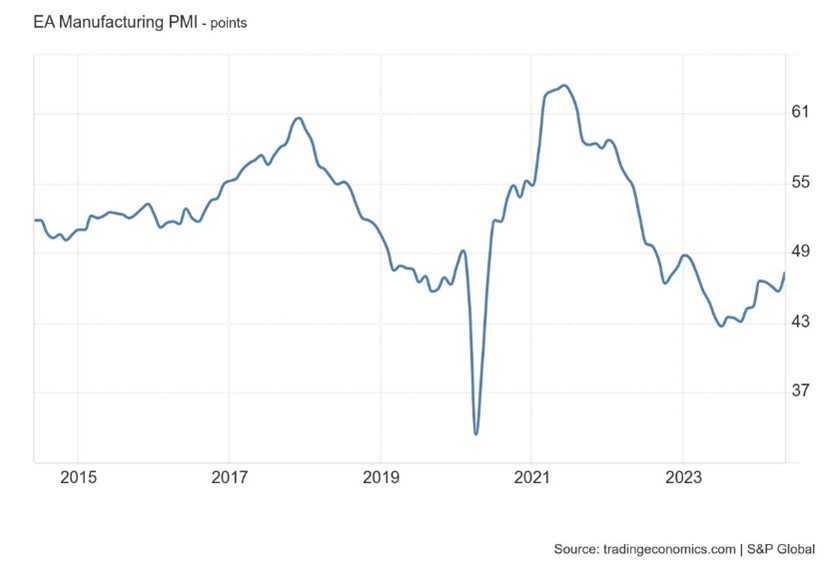

Indeed, in 2023, the key core countries like France and Germany were in outright recession after two years of accelerating inflation driven by high energy prices, as cheap Russian gas and oil was ditched (as part of the sanctions against Russia) in favour of expensive liquid gas imported from the US and elsewhere. As a result, Europe’s manufacturing sector has been contracting for the last two years (in the graph below 50 means contraction).

Investment growth has been very weak (and non-existent in the productive sectors like manufacturing).

There are still large disparities between the rich core of Europe and the poorest EU states, ie those in Eastern Europe that joined after the collapse of the Soviet Union and gained accession in 2004 and those in the southern parts of the region. However, relative stagnation in core Europe, particularly in recent years, has meant that the new 2004 members have closed the gap somewhat in living standards with the core.

In 2004, 75 million people across ten accession countries became citizens of the EU. Between 2004 and 2019, the GDP per capita of these countries almost doubled. According to the World Bank, based on its PPP measure, eight of the ten countries that joined the EU in 2004 were in the middle-income group in 2004 (except for Cyprus and Malta) and are now in the high-income group. One study reckons that almost a third of their current level of standard of living can be attributed to their accession to the EU (the opening-up of trade, easy movement of labour and capital flows as well as EU social funding). That contributed about half of the increase in GDP per capita between 2004 and 2019.

But to some extent, this ‘convergence’ (experienced by all new EU entrants in the past) is an illusion. Faster per capita real GDP growth over the core has been achieved mostly by falling populations, not by faster national output growth. People in the poor Eastern European states emigrated to the western states for work, just as people in the southern states of Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece had done in the past. They sent money back and so GDP per person rose.

Indeed, one big issue for Europe is the likely decline in population (particularly the working age population) as fertility rates fall. There are five countries in the world where the workforce is projected to grow by more than 10 per cent over the next 35 years. They are Ireland, Australia, the US, Canada and Norway. Two other countries, the UK and Sweden, are projected to have increases of between 5 and 10 per cent. Every other developed country should expect their working populations to fall. In Japan, it is falling already and is projected to decline by 35 per cent by 2050.

Germany faces a decline of nearly 30 per cent; Portugal, Italy and Greece by more than 20 per cent. The top ten countries with the fastest shrinking populations are all in Eastern Europe according to UN projections. Bulgaria, Latvia, Moldova, Ukraine, Croatia, Lithuania, Romania, Serbia, Poland, Hungary, are estimated to see their population shrink by 15% or more by 2050. For Ukraine, that forecast has increased.

Bulgaria is the world’s fastest shrinking country, with its population is expected to drop from 7 million in 2017 to 5.4 million in 2050. In Latvia, the population is estimated to drop from 1.9 million in 2017 to 1.5 million, whilst in Moldova, the population is estimated to shrink from 4 million to 3.2 million.

Europe needs to compensate for this demographic deficit with a significant rise in productivity. But Europe’s productivity levels (however, generously you measure it) remain 25% below that of the US, which has also experienced a slowdown in its productivity growth since the 1990s.

At the moment, many countries are reliant on a series of EU support schemes and exemptions that aim at softening the financial blow of the Covid-19 pandemic, including the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which saw EU countries issue joint debt for the first time. They are still providing a lifeline to countries with the most debt. The EU is pouring billions of euros into green and digital projects through this dedicated fund — worth over €700 billion. But this is set to run out at the end of 2026 and Germany and France are split over whether to maintain EU public spending and subsidies to sustain growth at the expense of rising deficits and debt; or cut back to meet previous EU budget targets.

One area where spending limits will not be imposed is defence. The message of the centrist party governments of northern Europe is that NATO and the US must be backed in its war with Russia over the invasion of Ukraine. Finland and Sweden, previously ‘neutral’ on NATO, have now joined, claiming a Russian threat to ‘European democracy’. Europe’s leaders’ message to its citizens is to ‘prepare for war.’ Military spending is up 7% this year with a target of 2% of GDP by each NATO member. That will eat into civil spending over the rest of this next EU parliament.

Europe’s capitalist sector is deeply worried. They fear being squeezed between the US and China in their intensifying geopolitical war, with exports to China, a previously big market, falling away while investment in China is reversed under US instructions. Already the war in Ukraine has badly hit European industry and increased costs across the board.

The profitability of capital in the core of Europe has slumped badly since the end of the Great Recession and through the Long Depression of the 2020s and with no recovery after the pandemic slump of 2020. France’s profitability is down over 30%, Germany’s over 25%.

Source: AMECO database

Even the new member states in the east (excepting Poland) have seen profitability falling.

Source: AMECO database

Europe’s relative decline economically and politically looks set to continue through this next EU Assembly period, and with increasing division and conflict in the Assembly and among member states on what direction to take. Voter turnout in Assembly elections is low: 42-51% in the last four votes. Interestingly, those Eastern European states that have gained most economically (at least for the business sector) have the lowest polling ratios (all well below 40%).

That does not mean that the EU is heading for a break-up. There is still strong support among Europe’s citizens for the idea of a ‘united Europe’, although support has fallen back since the pandemic and the subsequent inflationary spiral.

Throughout the Long Depression of the 2010s after the global financial crisis and the Euro debt crisis, not surprisingly, a majority of Europe’s citizens reckoned the economy was in bad way. Now surveys show that sentiment is about 50:50. It is generally people who consider themselves on the left that show the greatest support for the continuance of the EU. But a majority of those who consider themselves right wing are also in favour – even where there are EU-sceptic governments like Hungary or Slovakia. It is only in France and the UK that a majority of right-wing voters want to leave the EU. The UK left in 2020, with dire results for the UK economy and households.

However, if Europe’s economies continue to lose ground and European capital is increasingly squeezed by the global power battle between the US and China, that majority support for the EU idea may dissipate by the time of the next EU Assembly.

Be the first to comment