There is a lot of misleading hype about India as Michael explains

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

A general election in India starts today. 970m Indians, more than 10% of the world’s population, will head to the polls in what will be the largest election in history for the Lok Sabha (House of the People) parliamentary elections. The poll will spread across India and take up to 4 June to complete. Opinion polls suggest that Prime Minister Narendra Modi, leader of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and his coalition will win a third successive 5-year term, and win by some distance.

The main challenge to the BJP comes from a coalition of political parties headed by the Indian National Congress, the biggest opposition party. More than two dozen parties have joined to form the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (“India” for short). Key politicians in this group include Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge, as well as siblings Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi, whose father was the former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi.

The BJP was formed by members of what was basically a Hindu religious fascist party, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an organisation modelled on Mussolini’s Black Brigades. Modi was a long-time member of the RSS who then moved seamlessly into the BJP. After winning power in 2014, Modi has cemented his control of government. It is now seen as ‘business-friendly’, but the BJP is still dedicated to turning a multi-ethnic and multi-religious India into a Hindu state, where minorities, particularly Muslims, will be reduced to second-class citizens. With increasing confidence, the Modi government has suppressed any public dissent by liberal democrats and socialists against this trend. Many opposition politicians have been imprisoned on trumped-up charges and prevented from participating in the election and in public debate.

Opinion polls show that the BJP alliance will probably win this election with an increased majority, possibly enough to get a two-thirds majority in parliament, enabling the next government to push through further restrictions and laws against dissent. India’s reputation as the most long standing and largest ‘democracy’ in the Global South is being broken up.

How is it possible for the BJP and Modi to be so popular? First, because of the bulk of the BJP’s political support comes from the rural and more backward areas of this huge country who have not benefited from the strident rise of Indian capitalism in the cities. These areas are bulwarks of Hindu nationalism, incentivised by fear of muslims.

The second reason is the total failure over the decades of the main capitalist party and standard bearer of Indian independence, the Congress party, to deliver better living standards and conditions for the hundreds of millions, not only in the country but in the city slums. Congress appears to millions as the party of the establishment controlled by a family dynasty (the Gandhis), while the BJP appears to many as the populist party of the forgotten people.

The Modi government makes much of its handouts to the poorest. Welfare schemes have been expanded such as providing free grain to 800 million of India’s poorest, and a monthly stipend of 1,250 rupees ($16; £12) to women from low-income families paid into half a billion new bank accounts, along with free gas connection in millions of houses for the poor and over 40 million toilets constructed.

But in reality, the BJP and the Modi government is fully integrated and supportive of Indian capital, especially big capital. PM Modi has made the economy a major part of his election pitch, pledging at a rally last year to lift the country’s economy “to the top position in the world” should he win a third term. The Modi’s government’s key policy is Viksit Bharat 2047—a plan to make India a developed nation by 2047, 100 years after independence, something China is targeting for 2030.

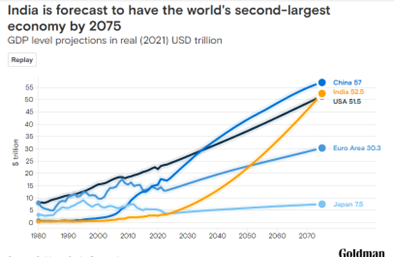

The Indian media and Western economists laud the strong economic growth that India is apparently enjoying under the Modi government. According to the official figures, Indian real GDP grew 8.4% yoy in the last quarter of 2023 and 7.6% over the whole year, up from 7.0% in 2022. So ecstatic are mainstream economists about the success of Indian capitalism under Modi that talk of his neo-fascist past and current repressive measures are ignored. Instead, all the talk is of India ‘catching up’ with China and even surpassing its real GDP soon. For example, Goldman Sachs projects India will have the world’s second-largest economy by 2075.

The forecast is that India will grow even faster while China’s growth slows and soon India will contribute more to global growth than China. India will take over China’s lead in manufacturing and technology and thus prove that a privatized, free market economy can triumph over a state-led planned one that is China. According to Bloomberg Economics, India could become the world’s No. 1 contributor to GDP growth as early as 2028 as India’s economic growth will accelerate to 9% by the end of this decade, while China will slow to 3.5%!

But all this is just hype. Take the growth figures. The perennial cry from Western economists when they get the growth figures for China is that they are faked. But actually, it is India’s national statistics office that is being ‘economical with the truth’. GDP figures contain dubious categories like ‘discrepancies’. These refer to the difference between real GDP growth of about 7.5% a year and real domestic expenditure growth of just 1.5% a year. They should be the same theoretically, but they are not – and the national statistical office ignores the latter. Part of the reason for the ‘discrepancy’ is that India’s government statisticians are ‘deflating’ money GDP into real GDP by a price deflator based on wholesale production prices and not on consumer prices, so that the real GDP growth figure is much higher than the real increase in spending. Also, the GDP figures are not ‘seasonally adjusted’ to take into account any changes in the number of days in a month or quarter or weather etc. Seasonal adjustment would have shown India’s real GDP growth well below the official figures.

What exposes the unrealistic figures the most is a recent paper on India’s staggeringly extreme inequality of wealth and income. The World Inequality Lab finds that “the present-day golden era of Indian billionaires has produced soaring income inequality in India—now among the highest in the world and starker than in the U.S., Brazil, and South Africa. The gap between India’s rich and poor is now so wide that by some measures, the distribution of income in India was more equitable under British colonial rule than it is now.”

The top 10% of the Indian population now holds 77% of the total national wealth. Between 2018 and 2022, India is estimated to have produced 70 new millionaires every day. Billionaires’ fortunes increased by almost 10 times over the last decade and their total wealth is higher than the entire national budget of India for the fiscal year 2018-19. The current total number of billionaires in India is 271, with 94 new billionaires added in 2023 alone, according to Hurun Research Institute’s 2024 global rich list.. That’s more new billionaires than in any country other than the US, with a collective wealth that amounts to nearly $1 trillion—or 7% of the world’s total wealth. A handful of Indian tycoons, such as Mukesh Ambani, Gautam Adani, and Sajjan Jindal, are now mingling in the same circles as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, some of the world’s richest people.

The report also found that the rise in inequality had been particularly pronounced since the BJP first came to power in 2014. Over the last decade, major political and economic reforms have led to “an authoritarian government with centralization of decision-making power, coupled with a growing nexus between big business and government,” the report states. This, they say, was likely to “facilitate disproportionate influence” on society and government.

In contrast, many ordinary Indians are not able to access the health care they need. 63 million of them are pushed into poverty because of healthcare costs every year – almost two people every second. Indeed, it would take 941 years for a minimum wage worker in rural India to earn what the top paid executive at a leading Indian garment company earns in a year. While the country is a top destination for ‘medical tourism’, the poorest Indian states have infant mortality rates higher than those in sub-Saharan Africa. India accounts for 17% of global maternal deaths, and 21% of deaths among children below five years.

Rural distress, stagnation and falling farming incomes have led to a number of protests by farmers. According to Samyukta Kisan Morcha, an umbrella of farm unions, over 100,000 farmers have committed suicide in the last ten years of Modi’s rule. India ranks 111th of the 125 nations in the Global Hunger Index (2023) report. India is home to over a third of the world’s malnourished children, which is not only a health crisis but has a wider impact on the economy. A 2023 joint report by FAO, UNICEF, WHO and WFP, found that 74% of the population cannot afford healthy food.

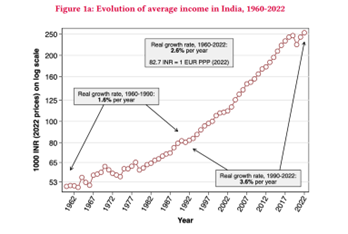

The WID averaged out national income growth between rich and poor. On that measure, growth in incomes in India is nowhere near the hype levels surrounding real GDP growth. Average real income growth in India is around 3.6% a year compared to the 6-8% claimed for real GDP growth.

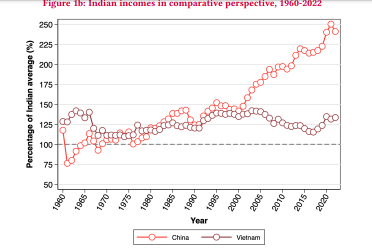

The idea that India is or will close the gap with China is a pipedream. Here the WID paper shows the gap between China’s average income, and that of India and Vietnam. Even Vietnam is holding its advantage over India.

India’s $3.5 trillion economy remains dwarfed by the $17.8 trillion Chinese economy. It would take a lifetime for India to catch up with its shoddy roads, patchy education, red tape and a lack of skilled workers.

The Indian economy is failing to create jobs, especially those that would support a dignified standard of living. Apart from public administration, the most rapid income growth by far this past quarter (at 12.1%) was in finance and real estate. But this neo-liberal feature of Indian development, now augmented by “fintechs,” generates only a handful of jobs for highly qualified Indians. Among other growth sectors, construction (helped by the government’s infrastructure drive) and low-end services (in trade, transport, and hotels) mostly create financially precarious jobs that leave workers one life event away from severe distress. The labour force participation rate in India has declined over the last 15 years. Under Modi, less than half the adult working population is employed.

Two-thirds of Indian workers are employed in small businesses with less than ten workers, where labour rights are ignored – indeed most are paid on a casual basis and in cash rupees, the so-called ‘informal’ sector that avoids taxes and regulations. India has the largest ‘informal’ sector among the main so-called emerging economies. India’s post-COVID manufacturing performance has been particularly weak. This reflects the country’s chronic inability to compete in international markets for labour-intensive products – a problem made worse by the slowdown in world trade and weak domestic demand for manufactured products.

Overall, government spending on health has fallen and now hovers around an abysmal 1·2% of gross domestic product, out-of-pocket expenditure on health care remains extremely high, and flagship initiatives on primary health care and universal health coverage have so far failed to deliver services to people most in need. Another contentious issue is the lack of credibility of India’s continuing claim that only 0·48 million people died as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas WHO and other estimates are six to eight times larger (including excess deaths, most of which will be due to COVID-19). India is right down at the bottom in terms of government spending. Only South Africa which is in a serious economic situation is lower than India.

And there is the issue of basic resources for India’s 1.4 billion people. Mechanically pumped groundwater now provides 85% of India’s drinking water and is the main water source for all uses. North India’s groundwater is declining at one of the fastest rates in the world and many areas may have already passed “peak water”. The World Bank predicts that a majority of India’s underground water resources will reach a critical state within 20 years. In pre-COVID 2019, China invested about 6.5% of its GDP in infrastructure development, while India invested just 4.5%. About 78% of Indians are literate — but the percentage drops to 62% for women. On the other hand about 97% of Chinese nationals are literate. About 1.6 million Indians are enrolled in vocational education; in China it’s about 5.6 million people.

Productivity growth has been falling for most of the years under the Modi government. Since Modi came to office, India’s average labour productivity growth has been 4% a year; China’s 6.3%.

Productivity would rise if generally underemployed peasants could move to the cities and get manufacturing jobs in the cities. This is how China transformed its workforce, to raise productivity and wages. China has done this through state planning of labour migration and huge infrastructure building. India cannot; its rate of urbanisation is way behind that of China. As a result, employment growth is pathetically slow. An estimated 10-12m young Indian people are entering the workforce each year but many cannot find jobs due to their paucity or because they lack the right skills.

And just compare India’s per capita GDP with that of China. It’s all you need to know about ‘catching up’! Note that China and India had more or less the same per capita GDP back in 1990.

And if the post-pandemic period is anything to go by, the ‘China gap’ is widening, not narrowing.

One good measure of a better life is the World Bank’s Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI covers economic growth, life expectancy and educational attainment. If we look at the largest so-called emerging economies by population, including the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), China has achieved the greatest improvement in its HDI of all countries. From a lowly 0.48 in 1990, China’s HDI reached 0.77 in 2021, a rise of 59%. Compare that to India, which started pretty much at the same HDI as China but reached only 0.63 in 2021, a rise of 46% but still way less than China.

Rather than ‘catch up’ and surpass China, it is more realistic to expect that India will stay in what the World Bank has called a ‘middle-income’ trap, where the vast majority of population remain in poverty while the top 10% live well and spend, but there is no investment or drive to deliver employment, training, education and housing for the rest.

The key for Indian capitalism is the profitability of its business sector. The profitability of Indian capital took a huge plunge in the 1970s, as profitability did globally. Under successive Congress-led governments, neo-liberal policies were adopted to drive up profitability. Then came the Great Recession and the ensuing Long Depression and profitability and growth began to fall back.

Electoral support for Congress drained away as a result and Hindu nationalism emerged. The BJP claimed that the reason for poor growth, rising inequality and stagnant living standards was ‘the enemy within’ (muslims) and ‘the big state’ as represented by a corrupt Congress family dynasty. Modi was the new saviour. But since then Modi has just endorsed policies agreeable to Indian big business: privatisation, cuts in food and fuel subsidies and a new sales tax, a tax that is the most regressive way to get revenue as it hits the poor the most.

With Modi set to win another five-year term, the ‘success’ hype will be intensified, but so will reductions in the right to dissent and oppose the nationalist government. And it will be business as usual for India’s billionaires. The Indian Raj will rule.

Be the first to comment