Michael Roberts general assesment of the current world economy. The global economic slowdown will be especially hard on the EU, which pushed by Germany, has become reliant on exports. Declining world growth means declining demand – for European exports.

Michael Roberts – Economist in the City of London and prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts Blog

The world economy continues to show significant signs of a slowdown. Back in April 2018, I reckoned that the mini-boom of 2016-17 had peaked and the world economy would now descend into another Kitchin cycle downswing. Moreover, this showed that nearly ten years from the end of the Great Recession in mid-2009, the world economy was still stuck in a Long Depression, or ‘secular stagnation’ (in Keynesian language).

Last month, data showed that the German economy, the powerhouse of Europe, had only narrowly avoided a ‘technical recession’ in the second half of 2018. This was partly caused by the global slowdown in the auto sector due a sharp drop in demand along with restrictions on diesel car emissions. Now in February, the EU Commission slashed its real GDP growth forecasts. The Commission cut its Eurozone growth forecast for this year to 1.3% from 1.9% in its earlier forecast last autumn, citing “large uncertainty” from Brexit negotiations, slowing growth in China and weakening global trade. At the same time, the Bank of England cut its forecast for the country’s economic outlook in the wake of greater uncertainty over Brexit and a slowdown in global growth. The downgrade for 2019 growth expectations to 1.2% is the weakest level in a decade. The Eurozone growth rate for the last quarter of 2018 is already there.

The last week, we got the figures for UK real GDP growth at the end of 2018. Real GDP growth was just 0.2% in Q4 2018 over the previous quarter. Indeed, the industry and construction sectors actually contracted. Manufacturing output has been shrinking for six months. Real GDP growth year over year (ie from Q42017 to Q4 2018) has slowed to just 1.2% (meeting the BoE forecast for 2019 already). This was the slowest annual rate since 2012. UK business investment in new technology, plant and equipment has also slumped badly – down for four consecutive quarters and down nearly 4% yoy. As a percentage of GDP, business investment has been falling for over three years. British business is on an investment strike. The risk of an outright recession in the UK this year has risen sharply.

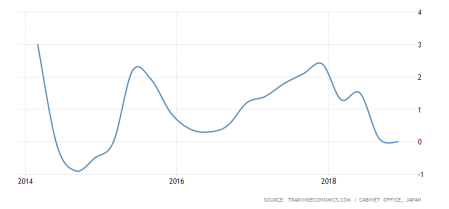

What’s happening in the UK economy is not all due to uncertainty over what happens with Brexit. It is also due to the global slowdown, particularly in Europe and China. Japan is teetering on a recession, with growth in the last quarter of 2018 at zero.

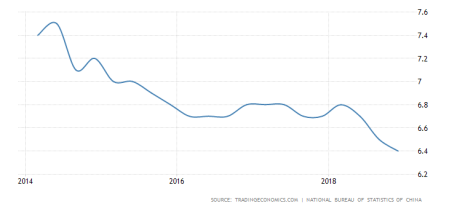

China’s growth rate continues to slow – if still far higher than anything in the advanced capitalist economies.

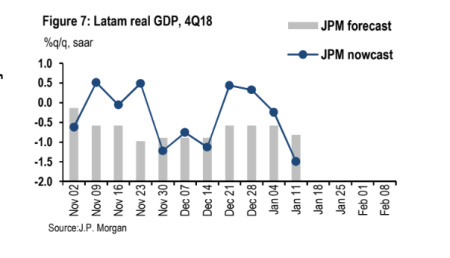

And, as I pointed out in a previous post, among the so-called ‘emerging economies’, emergence is being replaced by submergence. Real GDP in Latin America as a whole is contracting on annualised basis, according to investment bank JP Morgan.

But the key to whether this slowdown becomes an outright recession (mainstream economics defines that as two consecutive quarterly declines in real GDP) is what happens in the largest and most important capitalist economy, the US. Up to now, the US has been the leader of the pack, at least among the top G7 economies, with a real GDP growth rate of 3% at the end of 2018.

But as many have argued, this growth rate is ‘fake news’ as President Trump might put it. It has been driven by huge tax cuts for US corporations that have boosted profits by up to 30% in the last year. The impact of these will soon wear off in 2019. And it is already happening. According to the forecast of the Atlanta Federal Reserve, real GDP growth in the US will slow to just 1.5% in this current first quarter of 2019.

This latest forecast was a huge drop from the already slower 2% than Atlanta previously forecast. That was because of really bad retail sales figures announced last week. These may have been distorted by the US government shutdown in January and seasonal factors, but even so it is clear that the US economy is beginning to join Europe, Asia and Latin America in a significant downturn.

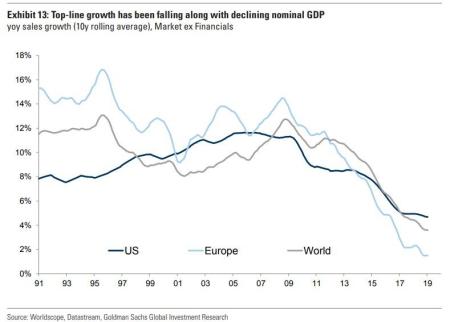

Actual nominal GDP has continued to weaken in the US, and even more so in Europe and Japan. The Long Depression continues.

In my view, there are two key factors that drive a capitalist economy: 1) investment in the capitalist sector and 2) the profitability of that investment. The latter decides the former, after a lag (according to empirical studies, usually a lag of about one year).

It seems that global investment is now stalling. JPMorgan investment bank economists are signalling a significant slowdown in global investment spending in the first quarter of 2019. “In sum, we have worried for some time that the sustained slide in global business confidence would translate into a meaningful deceleration in capex. This appears to be happening now, especially following the tightening in financial conditions in 4Q18. Indeed, the data we have in hand might not reveal the full extent of this pullback.”

The JPM economists cite “business confidence” and “tightening financial conditions”, by which they mean that companies are worried about future profitability and sales alongside rising interest costs on debt. Will the budding trade war between the US and China explode? Will the Fed and other central banks continue to raise their policy interest rates and thus ‘tighten’ financial conditions?

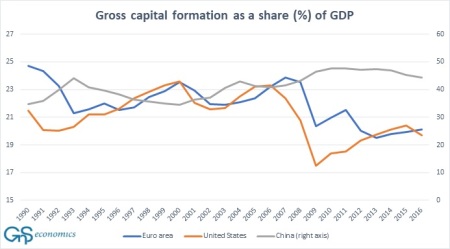

But rather than consider the psychology of capitalists, it is more rewarding to consider the objective conditions, because the latter informs the former. Globally, business investment has been in decline (as a share of GDP) since the end of the Great Recession. This relative decline has been led by the US and Europe.

It is often argued that investment to GDP is now lower because modern corporations don’t need to invest so much in tangible assets like equipment, offices and factories, because investment is now increasingly in ‘intangibles’, like patents, ‘intellectual property rights’ and software (even ‘goodwill’). But the evidence for this conclusion remains highly dubious. See Olivier Blanchard’s note on this here.

Then there is the argument that companies like Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon etc have merely hoarded their profits as cash or switched it into buying back their own shares to improve the financial value of their companies and boost the top executives bonuses. But this latter explanation, in my view, merely confirms that the real reason for lower business investment to GDP is that profitability of productive capital globally remains near post-war lows and for most economies is still below the level reached in 2006 or the late 1990s.

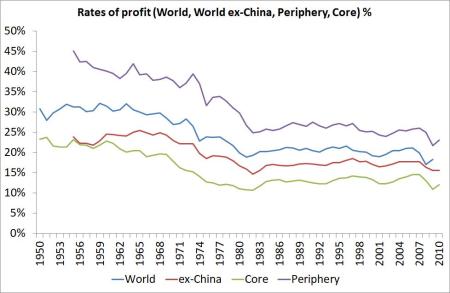

Here is the level of profitability of capital globally as calculated by Esteban Maito in our recent book, World in Crisis, Chapter 4.

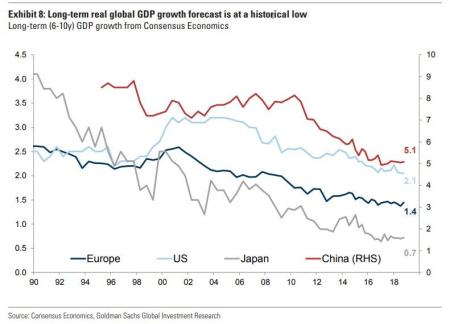

And here is the secular decline in real GDP growth in the advanced capitalist economies that accompanies the secular fall in profitability (as calculated by Alan Freeman in a new paper.

The_sixty-year_downward_trend_of_economi)

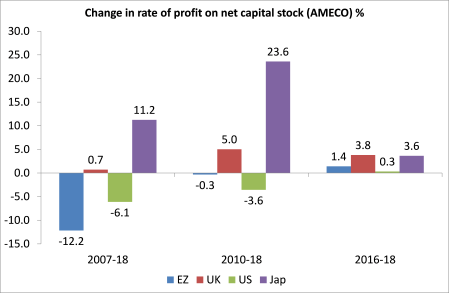

And here is what has happened to the profitability of capital from the beginning of the credit crunch in 2007 and the ensuing global financial crash and Great Recession, followed by the weak recovery and the Long Depression.

Over the whole period, Eurozone and US profitability is still below the 2007 level, while UK profitability is virtually flat. Only Japan shows a rise. In the ‘recovery’ period of 2010-18, profitability in the US and the Eurozone failed to recover. But in the recent mini-boom, there was some positive rise.

Actually, the big American tech companies (FAANGS) are the exception that proves the rule. There are whole swathes of smaller capitalist enterprises that are struggling to deliver enough revenues and profits to service their debts even though interest rates have remained way lower than before the global financial crash. I have covered this issue of zombie companies in previous posts, but the subject takes on an increasing relevance if ‘financial conditions’, as JPM calls it, continue to tighten globally. Indeed, according to another investment bank, Goldman Sachs, corporate sales growth is now at its lowest rate (on a 10-year rolling basis) since 1945!

If sales growth is weak and interest costs rise, then profits will be squeezed. Goldman’s economists note that since 2010, profit growth outside the US has stalled. The only place where corporate earnings have expanded is in the US. And this, according to Goldman’s is entirely down to those super-tech companies. Global profits ex technology are only moderately higher than they were prior to the financial crisis, while technology profits have moved sharply upwards (mainly reflecting the impact of large US technology companies), driven by a combination of strong sales growth and sharply rising margins.

Global growth is set to slow sharply in 2019. This is because business investment growth, already weak in the Long Depression, is going to drop off further. In turn, that investment slowdown is driven by low profitability in most economies and in most sectors. Only the huge tech companies in the US have bucked this trend, helped by a recent profits bonanza from the Trump tax ‘reforms’. But as the effect of those handouts wear off this year, tech profits may also head downwards – even if the US and China reach a trade deal.

Be the first to comment