An analysis of the risks involved in the response to the coronavirus. before, during, and after.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts Blog

There are now two billion people across the world living under some form of lockdown as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. That’s a quarter of the world’s population. The world economy has seen nothing like this. Nearly all economic forecasts for global GDP in 2020 are for a contraction of 3-5%, as bad if not worse than in the Great Recession of 2008-9.

According to the OECD, output in most economies will fall by an average of 25% (OECD) while the lockdowns last and the lockdowns will directly affect sectors amounting to up to one third of GDP in the major economies. For each month of containment, there will be a loss of 2 percentage points in annual GDP growth.

This is a monstrous way of proving Marx’s labour theory of value, namely that “Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish.” (Marx to Kugelmann, London, July 11, 1868).

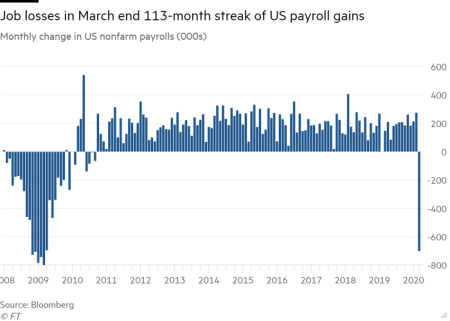

The lockdowns in several major economies are having a drastic effect on production, investment and, above all, employment. The latest jobs figures for March out of the US were truly staggering, with a monthly loss of 700,000 and a jump in unemployment to 4.4%.

In just two weeks, nearly 10m Americans have filed for unemployment benefit.

All these figures surpass anything seen in the Great Recession of 2008-9 and even in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Of course, the hope is that this disaster will be short-lived because the lockdowns will be removed within a month or so in Italy, Spain, the UK, the US and Germany. After all, the Wuhan lockdown is ending this week after 50 days and China is gradually returning to work – if only gradually. In other countries (Spain and Italy), there are signs that the pandemic has peaked and the lockdowns are working. In others (UK and US), the peak is still to come.

So once the lockdowns are over, then economies can quickly get back to business as usual. That’s the claim of US treasury secretary Mnuchin: “This is a short-term issue. It may be a couple of months, but we’re going to get through this, and the economy will be stronger than ever. Keynesian guru Larry Summers echoed this view: “I have the optimistic guess—but it’s only an optimistic guess—that the recovery can be faster than many people expect because it has the character of the recovery from the total depression that hits a Cape Cod economy every winter or the recovery in American GDP that takes place every Monday morning.”

During the lockdowns, various governments have announced cash handouts and boosted unemployment benefits for those laid off or ‘furloughed’ until business is restored. And small businesses are supposedly getting relief in rates and cheap loans to tide them over. That should save people’s livelihoods during the lockdowns.

One problem with this view is that, such have been the cuts in public services over the last decade or so, there is just not enough staff to process claims and shift the cash. In the US, it is reckoned that many will not get any checks until June, by which time the lockdowns might be over! Moreover, it is clear that many people and small businesses are not qualifying for the handouts for various reasons and will fall through this safety net.

For example, 58% of American workers say they won’t be able to pay rent, buy groceries or take care of bills if quarantined for 30 days or less, according to a new survey from the Society for Human Research Management (SHRM). One in five workers said they’d be unable to meet those basic financial needs in less than one week under quarantine. Half of small businesses in the U.S. can’t afford to pay employees for a full month under quarantine conditions. More than half of small businesses expect to see a loss in revenue somewhere between 10-30%.

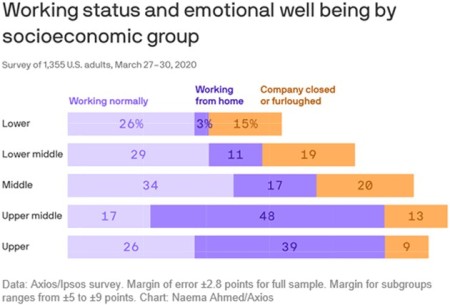

Indeed, many people are being forced to work, putting their health at risk because they cannot work at home like better paid, office-based workers.

Many small businesses in travel, retail and services will never come back after the lockdowns end. Even large companies in retail, travel and energy could well go bust, causing a cascade effect through sectors of economies. For example, the US Federal Reserve requires banks to run stress tests that assume certain bad scenarios to make sure the banks can weather a market downturn. The worst-case scenario had GDP falling by 9.9% in Q2 2020 with unemployment jumping to 10% by Q3 2021. Based upon recent estimates from Goldman Sachs, GDP will likely fall over 30% and unemployment could end up at a similar level… within weeks.

Also there are huge amounts of corporate debt issued by fairly risky companies which were not making much revenue and profit anyway before the pandemic. And as I have said in previous posts, even before the virus hit the world economy, many countries were heading into recession. Mexico, South Africa and Argentina among the G20 nations and Japan in the G7 were already in recession. The Eurozone and the UK were close and even the best performer, the US, was slowing fast. Now all that corporate debt that built up in the years since the end of the Great Recession could come tumbling down in defaults.

That is especially the case in the impoverished ‘Global South’ economies, which have experience an unprecedented $90bn outflow of capital as foreign investors leave the sinking ship. And there is little or no safety net being offered by the likes of the IMF or the World Bank. Things are only going to get worse in the coming quarter and recovery may not be anywhere near the optimists’ view in H2 2020.

Clearly these lockdowns cannot go on forever, otherwise billions of people are going to be destitute and governments will be spending more and more, funded by more and more debt and/or the printing of money to make cash handouts and buy yet more debt. You cannot go on doing that if there is no production or investment. Jobs will disappear forever and inflation will eventually rocket. We shall enter a world of permanent depression alongside hyper-inflation.

It seems that several European countries, encouraged by the peaking of cases are preparing to end their lockdowns by the end of this month. But even if they do, a return to ‘normal’ will take months as it will depend on mass testing to gauge whether the virus will come back as it surely will and whether it could then be contained while gradually restoring production. So any global recovery is not going to quick at all. A German Ifo study predicted the German economy could shrink by up to 20% this year if the shutdown lasted three months and was followed by only a gradual recovery.

And the latest US forecasts from Goldman Sachs show the trough of the US recession being reached in the second quarter of 2020, with GDP likely to be 11-12 per cent below the pre-virus reading. This would involve a dramatic decline at an annualised rate of 34 per cent in that quarter. GDP is then projected to rise very gradually, not reaching its pre-virus path before the end of 2021. This pattern, implying almost two “wasted” years in the US, has been common in recent economic forecasts. A similar picture is expected in the eurozone, which is experiencing a collapse in manufacturing output more precipitous than in the 2012 euro crisis.

But the gradual plan is the only óptimal’ option, says one bunch of economists: “importantly, the level of the lockdown, its duration, and the underlying economic and health costs depend critically on the measures that improve the capacity of the health system to cope with the epidemic (testing, isolating the vulnerable, etc.) and the capacity of the economic system to navigate through a period of suspended economic activities without compromising its structure.”

Could the lockdowns have been avoided? The evidence is increasingly clear that they could have been. When COVID-19 appeared on the scene, governments and health systems should have been ready. It is not as if they had not been warned by epidemiologists for years. As I have said before, COVID-19 was not an ‘unknown unknown’. In early 2018, during a meeting at the World Health Organization in Geneva, a group of experts (the R&D Blueprint) coined the term “Disease X”: They predicted that the next pandemic would be caused by an unknown, novel pathogen that hadn’t yet entered the human population. Disease X would likely result from a virus originating in animals and would emerge somewhere on the planet where economic development drives people and wildlife together.

More recently, last September the UN published a report warning that there is a “very real threat” of a pandemic sweeping the planet, killing up to 80 million people. A deadly pathogen, spread airborne around the world, the report said, could wipe out almost 5 percent of the global economy. “Preparedness is hampered by the lack of continued political will at all levels,” read the report. “Although national leaders respond to health crises when fear and panic grow strong enough, most countries do not devote the consistent energy and resources needed to keep outbreaks from escalating into disasters.” The report outlined a history of deliberate ignoring of warnings by scientists over the last 30 years.

Governments ignored the warnings because they took the calculated view that the risk was not great and therefore spending on pandemics prevention and containment was not worth it. Indeed, they cut back spending in pandemic research and containment. It reminds me the decision of Heathrow airport in the UK to buy only two snow ploughs because it hardly ever snowed or froze in London, so the expense was not justifiable. The airport was badly caught out one winter day and everything stopped.

How could the lockdowns have been avoided? If government had been able to test everybody for the virus, to provide protective equipment and huge armies of health workers to test and contract trace and then quarantine and isolate those infected. The old and sick should have been shielded at home and supported by social care. Then it would have been possible for everybody else to go to work, just as essential workers must do so now. Small countries like Iceland (and Taiwan, South Korea) with high quality health systems have been able to do this. Most countries with privatised or decimated health systems have not. So lockdowns have been the only option if lives are to be saved.

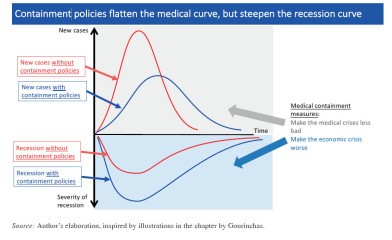

The policy of the lockdowns is only partly to save lives; it is also to try and avoid health systems in countries being overwhelmed with cases, leaving medics with the Hobson choice of choosing who will die or will get help. The aim is to ‘flatten the curve’ in the rise in virus cases and deaths so that health system can cope. The problem is that flattening the curve in the pandemic by lockdowns increases downward curve in jobs and incomes for hundreds of millions.

And yet if the pandemic were allowed to run riot, historical studies show that it also would eventually destroy an economy. A recent Federal Reserve paper, looking at the impact of the Spanish flu epidemic in the US, found that the then uncontrolled pandemic reduced manufacturing output by 18%. So lockdowns may be less damaging in the end. It seems you cannot win either way.

Lives or livelihoods? Some right-wing ‘neoliberal’ experts reckon that the capitalist economy is more important than lives. After all, the people dying are mostly the old and the sick. They do not contribute much value to capitalist production; indeed they are a burden on productivity and taxes. In true Malthusian spirit, in the executive suites of the financial institutions, the view is prevalent that governments should let the virus rip and once all the young and healthy get immune, the problem would be solved.

This view also connects with some health expert studies that point out that every day, hospital doctors must make decisions on what is the most ‘cost effective’ from the point of view of health outcomes. Should they save a very old person with COVID-19 if it means that some younger person’s cancer treatment is delayed because beds and staff have been transferred to the pandemic?

Here is that view: “if funds are not limitless – then we should focus on doing things whereby we can do the most good (save the most lives) for the least possible amount of money. Or use the money we have, to save the most lives.” Health economics measures the cost per QALY. A QALY is a Quality Adjusted Life Year. One added year of the highest quality life would be one QALY. “How much are we willing to pay for one QALY? The current answer, in the UK, is that the NHS will recommend funding medical interventions if they cost less than £30,000/QALY. Anything more than this is considered too expensive and yet the UK’s virus package is £350bn, almost three times the current yearly budget for the entire NHS. Is this a price worth paying?” This expert reckoned that “the cost of saving a COVID victim was more than eleven times the maximum cost that the NHS will approve.” At the same time cancer patients are not being treated, hip replacements are being postponed, heart and diabetes sufferers are not being dealt with.

Tim Harford in the FT took a different view. He points out that the US Environmental Protection Agency values a statistical life at $10m in today’s money, or $10 per micromort (one in a million risk of death) averted. “If we presume that 1 per cent of infections are fatal, then it is a 10,000 micromort condition. On that measure, being infected is 100 times more dangerous than giving birth, or as perilous as travelling two and a half times around the world on a motorbike. For an elderly or vulnerable person, it is much more risky than that. At the EPA’s $10 per micromort, it would be worth spending $100,000 to prevent a single infection with Covid-19. You don’t need a complex epidemiological model to predict that if we take no serious steps to halt the spread of the virus, more than half the world is likely to contract it. That suggests 2m US deaths and 500,000 in Britain — assuming, again, a 1 per cent fatality rate. If an economic lockdown in the US saves most of these lives, and costs less than $20tn, then it would seem to be value for money.” The key point for me here is that this dilemma of ‘costing’ a life would be reduced if there had been proper funding of health systems, sufficient to provide ‘spare capacity’ in case of crises.

There is the argument that the lockdowns and all this health spending are based on an unnecessary panic that will make the cure worse than the disease. You see, the argument goes, COVID-19 is no worse than bad flu in its mortality rate and will have way less impact than lots of other diseases like malaria, HIV or cancer, which will kill more each year. So stop the crazy lockdowns, just protect the old, wash your hands and we shall soon see that COVID is no Armageddon.

The problem with this argument is that evidence is against the view that COVID is no worse than annual flu. It’s true that, so far, deaths have only reached 70,000 by April, some 40,000 less than flu this year and only quarter of the deaths from malaria.

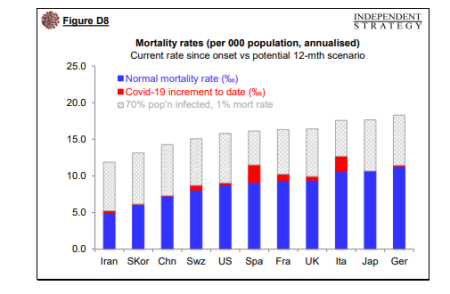

But the virus ain’t over yet. So far, all the evidence suggests that the mortality rate is at least 1%, ten times more deadly than annual flu; and is way more infectious. So if COVID-19 were not contained it would eventually affect up to 70% of the population before ‘herd immunity’ would be sufficient to allow the virus to wane. That’s 50 million deaths at least! Annual mortality rates would be doubled in most countries (see graph).

Moreover, this is a virus that is novel and different from flu viruses and there is no vaccine yet. It is very likely to come back and mutate and so require yet more containment.

Some governments are risking people’s lives by trying to avoid total or even partial lockdowns to preserve jobs and the economy. Some governments have put in place sufficient testing and contact tracing along with self-isolation, to claim that they can keep their economies going during the crisis .Unfortunately for them, even if that works, the lockdowns elsewhere have so destroyed trade and investment globally, even these countries cannot avoid a slump with global supply chains paralysed.

There is another argument against the lockdowns and saving lives. A study by some Bristol University ‘safety experts’ reckoned that a “business as usual” policy would lead to the epidemic being over by September 2020, although such an approach would lead to a loss of life in the UK nearly as much as it suffered in the Second World War. But conversely, lockdowns could decrease GDP per head so much that the national population loses more lives as a result of the countermeasures than it saves.

But the Bristol study is just a risk assessment. Proper health studies show that recessions do not increase mortality at all. A recession – a short-term, temporary fall in GDP – need not, and indeed normally does not, reduce life expectancy. Indeed, counterintuitively, the weight of the evidence is that recessions actually lead to people living longer. Suicides do indeed go up, but other causes of death, such as road accidents and alcohol-related disease, fall.

Marxist health economist Dr Jose Tapia (also an author of one of the chapters in our book World in Crisis) has done several studies on the impact of recessions on health. He found that mortality rates in industrial countries tend to rise in economic expansions and fall in economic recessions. Deaths attributed to heart disease, pneumonia, accidents, liver disease, and senility—making up about 41% of total mortality—tend to fluctuate procyclically, increasing in expansions. Suicides, as well as deaths attributable to diabetes and hypertensive disease, make up about 4% of total mortality and fluctuate countercyclically, increasing in recessions. Deaths attributed to other causes, making up about half of total deaths, don’t show a clearly defined relationship with the fluctuations of the economy. “All these effects of economic expansions or recessions on mortality that can be seen, e.g., during the Great Depression or the Great Recession, are tiny if compared with the mortality effects of a pandemic,” said Tapia in an interview.

In sum, the lockdowns could have been avoided if governments had taken notice of the rising risk of new pathogen pandemics. But they ignored those warnings to ‘save money’. The lockdowns could have been avoided if health systems had been properly funded, equipped and staffed, instead of being run down and privatised over decades to reduce costs and raise profitability for capital. But they weren’t.

And there is the even bigger picture. If you have enough firemen and equipment, you can put out a bush fire after much damage, but if climate change is continually raising temperatures, another round of fires will inevitably come along. These deadly new pathogens are coming into human bodies because the insatiable drive for profit in agriculture and industry has led to the commodification of nature, destroying species and bringing nature’s dangers closer to humanity. Even if after this pandemic is finally contained (at least this year) and even if governments spend more on prevention and containment in the future, only ending the capitalist drive for profit will bring nature back into harmony with humanity.

For now, we are left with saving lives or livelihoods and governments won’t manage either.

Be the first to comment