The unexpected strength of the Russian economy, its foundations, effects, and perspective

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

This file comes from the website of the President of the Russian Federation and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

Today Russians are set to head to the polls for their country’s presidential election over three days – with only one expected outcome. Incumbent President Vladimir Putin will win comfortably. The Russian president is elected by direct popular vote. If no candidate receives over 50% of the vote, then a second round is held between the two most popular candidates three weeks later. It’s the first time that multi-day voting has been used in a Russian presidential election, as well as the first allowing voters to cast ballots online.

There is no serious opposition candidate that can win. In the 2018 presidential vote, the Communist party runner-up Pavel Grudinin secured 11.8% of the vote, compared to Putin’s 76.7%. This time Nikolai Kharitonov of the Communist Party, Leonid Slutsky of the nationalist Liberal Democratic Party, and Vladislav Davankov of the New People Party are on the ballot paper. But all these candidates broadly support Putin’s policies, including the invasion of Ukraine. The vast majority of independent Russian media outlets have been banned and anyone found guilty of spreading what the government deems to be “deliberately false information” can be imprisoned for up to 15 years.

Putin is going to win not just because he has decimated any serious opposition forces, but because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to have at least resigned support among Russian people, even if Russian lives are being lost. The main reason for that is because, contrary to the hopes and expectations of Western analysts, the Russian economy has not collapsed and Russian forces now seem to have the upper hand inside Ukraine.

Russia’s war economy is holding up. Wages have soared by double digits, the rouble is relatively stable and poverty and unemployment are at record lows. For the country’s lowest earners, salaries over the last three quarters have risen faster than for any other segment of society, clocking an annual growth rate of about 20%.

The government is spending massively on social support for families, pension increases, mortgage subsidies and compensation for the relatives of those serving in the military.

The war in Ukraine has intensified an acute labour shortage as military recruitment draws workers out of the market and with half a million Russians fleeing the country. Putin said last month that employers had a deficit of 2.5 million people. That has benefited those Russian workers not in the armed forces with security of employment as managers are reluctant to let anyone go. The unemployment rate remains at a historic low and hiring expectations have soared to a record level.

However, inflation has picked up; accelerating in February to 7.7% yoy. It’s just that wages are rising faster. Average monthly wages in 2023 reached more than 74,000 rubles ($814), about 30% higher than two years ago. Before last year, Russia had not seen an increase in real disposable income of more than 5% for many years.

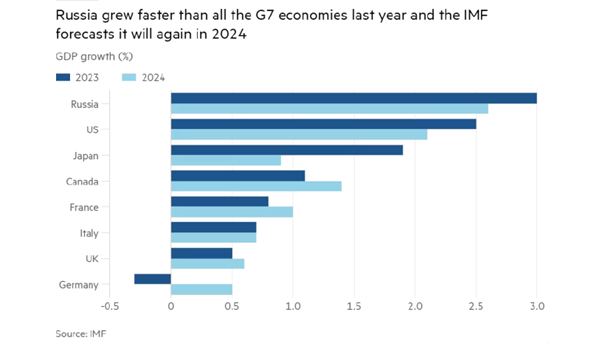

And Russia’s war economy is not plunging, but growing. The IMF forecasts real GDP growth in 2024 of 2.6%, outpacing the G7.

Over the past two years of war, Russia has managed to steer through sanctions, while investing nearly a third of its budget in defence spending. It’s also been able to increase trade with China and sell its oil to new markets, in part by using a shadow fleet of tankers to skirt the price cap that Western countries had hoped would reduce the country’s war chest. Half of its oil and petroleum was exported to China in 2023. And it became China’s top oil supplier in 2023, according to Chinese customs data. Chinese imports into Russia have jumped more than 60% since the start of war, as the country has been able to supply Russia with a steady stream of goods including cars and electronic devices, filling the gap of lost Western goods imports. Trade between Russia and China hit $240 billion in 2023, an increase of over 64% since 2021, before the war.

Contrary to Western forecasts, Russian industry has grown due to war-related production, while demand for domestic manufactures has also increased due to a fall in imports because of sanctions. The automobile industry – which was hit hard initially, as Western and Japanese car manufacturers left Russia en-masse – has been recovering strongly month by month, as Chinese companies have stepped in.

The level of capacity utilisation in the Russian economy has been generally rising and, according to various surveys, now stands at historically very high levels.

A war economy means that the state intervenes and even overrides the decision-making of the capitalist sector for the national war effort. State investment replaces private investment. Ironically, in Russia’s case this has been accelerated by Western companies’ withdrawal from Russian markets and by the sanctions. The Russian state has taken over foreign entities and/or resold them to Russian capitalists committed to the war effort.

But Russia’s war economy will revert to capitalist accumulation when the war ends. The Russian finance ministry estimates that war-related fiscal stimulus in 2022-23 was equivalent to around 10 per cent of GDP. In that same period, war-related industrial output has risen 35%, while civilian production remained flat (until recently), according to research published by the Bank of Finland Institute for Emerging Economies.

Elevated social and war spending has also resulted in a yawning budget gap. The federal budget gap was 1.5 trillion rubles by the end of February, while the Finance Ministry has planned for a deficit of 1.6 trillion rubles for the whole of 2024 and Russia’s available wealth fund reserves have been already halved. After the election, Russian people can expect higher taxes, at least for higher earners.

And the Russian economy remains fundamentally natural resource linked. It relies on extraction rather than manufacturing. Mining accounted for around 26% of gross industrial production in July 2023, and three industries – extraction of crude petroleum and natural gas, coke and refined petroleum products manufacturing and basic metals manufacturing – made up more than 40% of the total. “The regime is resilient because it sits on an oil rig,” says Elina Ribakova, a non-resident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “The Russian economy now is like a gas station that has started producing tanks.”

War production is basically unproductive for capital accumulation over the long run. And Russia’s potential real GDP growth is probably no more than 1.5% a year as growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population and low investment and productivity rates. The profitability of Russian productive capital before the war was very low.

The Russian war economy is well placed to continue the war for several years ahead if necessary, but when the war is over, Putin may face a significant slump in production and employment.

Be the first to comment