A key factor that has gone mostly unnoticed is that the pickup in US growth last year came from a sharp rise in net immigration

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

In 2023, US real GDP grew by 2.5% after inflation – much better than expected. This has been heralded by the media and mainstream economists as refuting the doomsayers that the US economy was heading into a slump. Now in 2024, the pundits claim that we can expect more of the same – reasonable real GDP growth but this time with a return to lower inflation and thus falling interest rates. Corporate bankruptcies will be avoided and the growing impact of new technologies and AI will raise the rate of growth in labour productivity, setting the scene for a strong period of improved living standards. Perfect.

A key factor that has gone mostly unnoticed is that the pickup in US growth last year came from a sharp rise in net immigration. In simple terms, more workers generate more goods and services. A larger number of people earning paychecks means more consumer spending. And more people paying income tax on earnings boosts tax revenues. Last year, the US population rose by 0.9% in 2023, much faster than the US Census Bureau forecast of 0.5%. And the prime-age workforce participation rate—ie 25- to 54-year-olds—reached 83.5% in February, matching highs that hadn’t been seen since the early 2000s. Much of this is due to immigration. The US economy is outperforming in GDP terms mainly because of net immigration, twice as fast as in the Eurozone and three times as fast as Japan.

US population growth is set to slow over the next 30 years; in the US from 0.6% per year between 2024 and 2034 to just 0.2% between 2045 and 2054. So net immigration is going to be the only way that the US population will rise, particularly after 2040 when US fertility rates will fall below the rate that would be required for a generation to replace itself in the absence of immigration.

Unless net immigration continues to be strong, the only way economic growth in the major capitalist economies will be sustained will be through increased productivity of labour. But productivity growth in all the major economies has been slowing. And so for example, if the US workforce grows by say 0.5% a year and labour productivity rises by say 1.5%, then US real GDP growth will average 2% over the next decade. But more than likely, both the workforce and productivity growth will be less, so real GDP growth will be much less, especially if immigration is curbed. Moreover, this assumes no major slump in the economy during the rest of the 2020s.

The US is home to more immigrants than any other country – more than 45 million people. Foreign-born workers now make up 18.6% of the civilian labour force in 2023, up from 15.3% in 2006. Without foreign-born labour, the US labour force would shrink because of lower birth rates and an aging workforce.

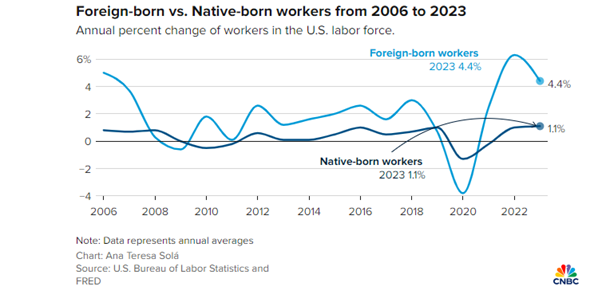

The growth rate of foreign-born workers was 4.4% in 2023 compared to native born workers of just 1.1%.

This net immigration is not by ‘illegals’. In 2021, only 4.6% of US workers were ‘unauthorised’, a share that’s pretty much unchanged since 2005. The Pew Research Center’s latest estimates indicate about 10.5 million undocumented immigrants live in the United States. That means the vast majority of foreign-born people living in the United States (77%) are here legally.

For decades, a national original quota system, passed by Congress in 1924, favoured migrants from northern and western Europe and excluded Asians. In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act created a new system that prioritised highly skilled immigrants and those who already had family living in the country. That paved the way for millions of non-European immigrants to come to the United States. In 1965, 9.6 million immigrants living in the US comprised just 5% of the population, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Now more than 45 million immigrants make up nearly 14% of the country. And most of these are skilled workers and their families.

That 13.6% of the US population is about the same as it was a century ago. But over the years, that has been a significant shift in where immigrants to the US come from. Mexicans still represent the largest group of immigrants living in the United States. And the Mexico-US route is the largest migration corridor in the world. But the total number of Mexican immigrants living in the US has been on the decline for more than a decade. An estimated 10.7 million Mexican immigrants lived in the US in 2021, roughly 1 million fewer than the number a decade earlier.

Meanwhile, immigration from other countries, including India and China, has been on the rise.

About 42% of all immigrants, or 638,551 people, came for work. And 39% of all immigrants were from Asia.

There has been a burst in immigration since the end of the pandemic which has helped sustain US GDP growth. “Reopening of borders in 2022 and easing of immigration policies brought a sizable immigration rebound, which in turn helped alleviate the shortage of workers relative to job vacancies,” Evgeniya Duzhak, regional policy economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, wrote in a 2023 paper. About 50 percent of the US labour market’s extraordinary recent growth came from foreign-born workers, according to an Economic Policy Institute analysis of federal data. And even before that, by the middle of 2022, the foreign-born labour force had grown so fast that it closed the labor force gap created by the pandemic, according to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

The influx of immigrants to work and to study is helping the US economy – it’s keeping a high supply of labour available for employers particularly in the areas of heavy demand for labour: healthcare, retail and leisure, also sectors of relatively low pay.

Net immigration is becoming vital to US capitalism. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. labour force will have grown by 5.2 million people by 2033, thanks mainly to net immigration and the economy is projected to grow by $7 trillion more over the next decade than it would have without new influx of immigrants.

But here is the rub. Americans now cite immigration as the country’s top problem, surpassing inflation, the economy and other issues with government. All the talk is of ‘illegals’ and Republican candidate for the 2024 election, former president Trump talks of deporting millions if re-elected as president – even though the ‘undocumented’ foreign-born population has been falling while legal immigrants have risen.

The usual (non-racist) argument against immigration is that wage levels of US workers will be reduced as native-born workers compete for jobs with foreign-born workers. But so far, all the evidence suggests not. A 2017 meta analysis of economic research on immigration conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggests the impact of immigration on the overall U.S.-born wage “may be small and close to zero,” particularly when measured over a period of 10 years or more. There are much more significant hits to labour’s share of value-added in the economy, namely globalisation, weaker unions and a stagnant federal minimum wage. And there are other reasons why labour force participation may have declined long-term: automation and technology reducing the demand for low-skilled labour; and the shift away from manufacturing and toward service-oriented jobs, which often require higher educational attainment.

For now, contrary to the Trumpist talk, immigration for US capitalism is good news. That could change if the US economy drops into a recession where jobs become scarce.

Be the first to comment