How very interesting. In England and Scotland, both former EU members, there are discussions raging outside the political parties about what should replace the pre-Coronavirus economic system. This is just one article by Richard Murphy concerning the tax system (see a previous article here). Well worth the read, as it applies for most EU nations as well. Still, amazing what leaving the EU can do for democracy.

Richard Murphy is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy, City University of London. He campaigns on issues of tax avoidance and tax evasion, as well as blogging at Tax Research UK

Cross-posted from Tax Research UK

Introduction

In the aftermath of the coronavirus crisis there appears to be a widely held opinion that taxes on wealth should increase. Both the Pope and Archbishop of Canterbury appear to share this view, for example. They do so with the objective of reducing inequality in society.

They are not alone. There have been many demands that this be an objective for the After Coronavirus era. For example, the Financial Times has said:

Radical reforms — reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades — will need to be put on the table. …. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.

In this context it is appropriate to test data on the existing tax system that operates in the UK to see whether this demand for increased taxation of wealth is reasonable at this time.

Summary

To achieve this goal a report has been prepared to appraise data on whether or not there is the capacity for those with wealth to pay more tax in the UK, or not. Having appraised data from the Office for National Statistics, HM Treasury and HM Revenue & Customs four main conclusions are reached.

The first is that in the period 2011 – 18 the national income of the UK was £13.1 trillion, and in that same period the increase in net wealth was £5.1 trillion. It is stressed, that this figure is not for total wealth, but the increase in the value of that net wealth in that period.

Second, the overall effective tax rates on income during this period were unlikely to have averaged more than 29.4%, but those on wealth increases did not exceed 3.4%.

Third, if these rates had been equalised it would, at least in principle, have been possible to raise an additional £174 billion in tax revenue per annum from the owners of wealth.

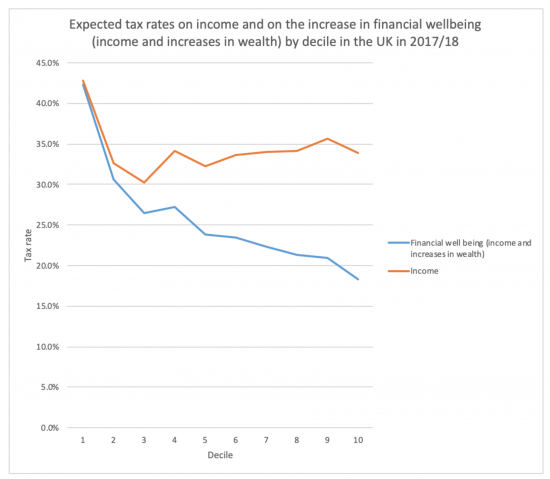

Fourth, because there has been no attempt at equalisation and because the distribution of the ownership of wealth varies substantially across the UK, which variation is reinforced by factors such as age and gender where substantial inequalities exist, the effective tax rate of the 10% of those in the UK who are in the lowest earning group of taxpayers exceeds 42% of their combined income and wealth gains in a year, but the equivalent effective tax rate for those in the highest ten per cent of UK taxpayers ranked by earnings is less than half that at just over 18 per cent. This is summarised in this chart:

It is, as a result, suggested that there is considerable additional capacity for tax to be raised from those who own most of the wealth in the UK, many of whom are in that top ten per cent of income earners.

Whether or not it would be desirable, or even technically feasible, to raise £174 billion of additional tax from additional tax charges on wealth is not the primary issue addressed by the paper. Nor does it concern itself with the issue of whether that sum should be redistributed simply to redress wealth inequality. A value judgement is not being offered on the matter of wealth holding, as such. Instead the issue of concern being addressed is that those most vulnerable to precarity within the UK are also those paying the highest overall effective rates of tax.

Whether that is appropriate is the first question raised as a consequence, with the second being whether, if that is the case, any tax increases that might arise in future should have any impact upon those with lower income or earnings. In the context of the coronavirus crisis and the debates that will, inevitably, occur at some point on whether and if taxes should be raised to contribute towards its cost, these appear to be issues of considerable significance.

This evidence in the paper suggests that those with substantially higher income and wealth should bear the majority or all of that cost if it was thought appropriate that anyone should.

That does, however, then suggest that it might also be important that the disparity in the relative tax payments made by those on high and low earnings in the UK should be addressed whether or not overall net additional tax revenue is required, or not. That is because there is now ample evidence that inequality creates significant social costs within any society, and it is apparent that the UK tax system is contributing to this problem.

A manifesto for change that could result from this understanding might include suggestion that:

- The considerable scope for increasing the effective tax rates on wealth and income derived from it should now be very firmly on the UK policy agenda;

- Any such increase must be targeted at those with the greatest capacity to pay, which would be those in the top deciles of income earners and wealth owners in the UK;

- Tax increases impacting the income of those in other deciles would be very hard to justify if measures to increase tax on wealth and income derived from it did not also happen;

- Inequality in the UK could be considerably reduced by taking the taxation of wealth into greater account. Which taxes should be cut for those on lower income levels to help achieve this goal also needs extensive consideration especially given the stresses that have emerged as a result of the coronavirus crisis.

These issues will be addressed in further posts on how this matter should be tackled in practice.

Be the first to comment