In an epic myth-busting exercise, Christine Lagarde recently affirmed that “the ECB will neither run out of liquidity nor fail”, weighing into an odd but highly important debate about the special nature of central bank accounting.

Stanislas Jourdan is Executive Director of Positive Money EU

Cross-posted from Positive Money EU

More than a decade ago, the global financial crisis forced major central banks across the world to intervene in unprecedented ways. This included purchasing vast amounts of assets from banks and financial institutions, through so-called quantitative easing.

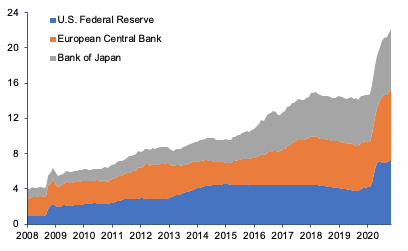

As a result, central banks’ balance sheets have ballooned as they piled up lots of debt in their portfolios, especially debt from governments. Central banks have virtually become the biggest investors on earth. The U.S. Federal Reserve ($7.2 trillion, 33% of GDP), ECB (€7 trillion, 55% of euro area GDP) and Bank of Japan’s ($6.7 trillion, 126% of GDP) combined balance sheet stands at $22.18 trillion as of end 2020.

Balance sheet of world’s largest central banks.

(Trillion $)

Source: St.Louis FRED.

In the Eurozone, the ECB started buying government bonds in smaller quantities in 2010 under the so-called Securities Markets Programme (SMP). SMP was essentially a precursor version of quantitative easing, restricted mostly to Southern European countries. Although the programme was broadly a failure due to its limited nature, it did temporarily delay the contagion of the self-fulfilling market panic and speculations against the Eurozone.

These unprecedented actions by central banks triggered all sorts of criticisms and controversies. One of these was the idea that by purchasing lots of debt, the ECB would unavoidably risk making huge losses, as some governments like those of Greece or Italy may default and require debt restructuring.

This question was at the heart of an intense debate a few years ago, with some naysayers arguing that QE programmes were putting taxpayers’ money on the line. Those orthodox economists claimed that if the ECB would accumulate losses on its balance sheet, it could become insolvent and require governments to provide a bail-out by putting more money into their capital share of the ECB. In other words, what the ECB can give with one hand, it will have to take it back with the other.

However, this was always an intellectual shortcut.

A central bank cannot lack something it can create infinitely

Central banks are public institutions which have been given the powerful role of creating a legal tender and supervising credit creation by private banks. Logically, and as explained extensively in the literature, a central bank cannot lack something it can create infinitely. It is, therefore, possible for a central bank to run into negative equity – that is, to appear financially insolvent on paper – without any immediate operational problems.

In this context, it is extremely reassuring that the ECB President Christine Lagarde has made a remarkably clear statement on this, when asked by French MEP Manon Aubry in a Written Question to the ECB:

“In response to your question on how the Eurosystem technically provides liquidity to the financial system, the Eurosystem, as part of its monetary policy measures, purchases securities – in net terms – and by doing so creates central bank money. Central bank money is also created when commercial banks, through the Eurosystem’s refinancing operations, borrow money from the Eurosystem against adequate collateral. The electronically created central bank money is held on the commercial banks’ accounts with their NCBs, which are also referred to as bank reserves with the central bank. As the sole issuer of euro-denominated central bank money (i.e. banknotes and bank reserves), the Eurosystem will always be able to generate additional liquidity as needed to fulfil its mandate. Therefore, as I had the opportunity to clarify at the last hearing at the ECON Committee, by definition, the ECB will neither run out of liquidity nor fail.”

This matter of fact should have been made clear long ago. But for reasons unknown, it was not mentioned, or at least not stated so clearly. For example, we remember an epic episode where Mario Draghi was asked a similar question by a Swedish journalist. Draghi was laughably embarrassed.

In contrast, Lagarde’s clear-cut response illustrates how ECB’s doctrine on this issue has finally evolved. It should now be put to bed for good.

Be the first to comment