Explaining once again why government deficits need not be seen as something negative, but play an essential role in a nation’s economy

Steve Keen is a Distinguished Research Fellow, Institute for Strategy, Resilience & Security, UCL

Cross-posted from Steve’s website Building A New Economics

On one side, we have Elon Musk as a critic of fiat money. On the other, we have Ford and Edison—the tech-billionaires of their time—as fans of fiat money. Who do you trust?

Neither: you work it out for yourself from first principles. And this is much harder that just ranting about “fiat money” on one side, or “barbarous relic” on the other.

So, if you really want to know what happens when a government spends more than it gets back in taxes, rather than just guessing, then you’re going to have to work out what happens in double-entry bookkeeping, since that is the “quantum mechanics” of money.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before, but the fundamental rules of double-entry bookkeeping are:

- All financial claims are classified as either Assets or Liabilities;

- The gap between your financial Assets—which are your claims on other people—and your financial Liabilities—which are other peoples’ claims on you—is known as your Equity; and

- All transactions are recorded twice, following the rule that Assets minus Liabilities minus Equity equals zero.

Now let’s see how a government deficit works. To make it as simple as possible to follow, I’m going to start without bond sales, and then add them in after we’ve seen how a Deficit works on its own.

When a government spends more than it gets back in taxes, it puts more money into people’s private bank accounts via spending than it takes out via taxes. Therefore, since private bank accounts are part of the money supply, a government deficit creates money.

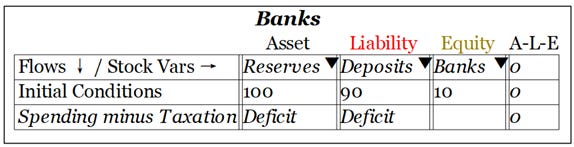

That’s one entry in the double-entry process. What’s the other? It’s an increase in Reserves—which are both an Asset of the Private Bank themselves, and a liability of the Central Bank.

Figure 2: A Deficit creates money by increasing both Deposits (Liabilities of the Banks) and Reserves (Assets of the Banks)

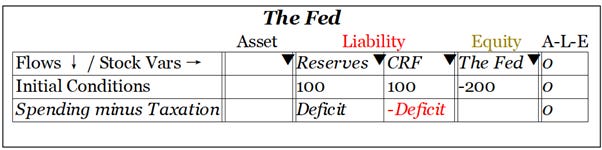

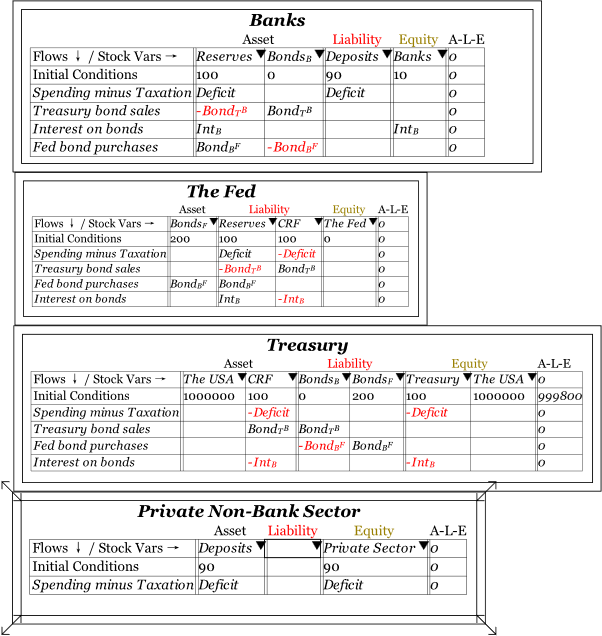

We therefore need to see the process from the Federal Reserve’s point of view. The Fed is the banker for both the private Banks and the Treasury. The Treasury’s numerous accounts at the Central Bank are lumped together into the “Consolidated Revenue Fund”, or CRF for short. The increase in Reserves shown in Figure 2 is caused by a transfer from the CRF, as shown in Figure 3. Since at present The Fed is shown as having only Liabilities, its equity is negative (this will change when we consider Treasury Bond sales).

Figure 3: The Deficit operation from The Fed’s point of view

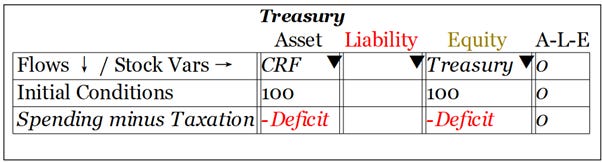

The CRF is an Asset of the Treasury, and a Deficit reduces it. How does this affect the Treasury: where does it get the money from?

The short answer is that it doesn’t: instead, the Deficit reduces the financial equity of the Treasury. This is shown in Figure 4. Obviously, even though I’ve shown the Treasury as being in positive equity thanks to the 100 in its CRF account, obviously a sustained Deficit would exhaust this account, and put the Treasury in negative equity overall.

Figure 4: The Deficit from the Treasury’s point of view

This is the step which annoys Elon Musk and other critics of fiat money: the Treasury doesn’t “get the money” from somewhere else: there is no “pot of gold”, no vault, no “Aladdin’s Cave”, by which the Deficit is financed. Instead, the Deficit pushes the government into negative financial equity. This is something that, if any other entity in society did consistently, would lead to bankruptcy.

However, therein lies the clue as to why the government can sustain negative financial equity: a company can do the same, so long as its nonfinancial assets are much larger than its negative financial equity.

A nonfinancial asset is an Asset to its owners, but a liability to no one: things like houses (and even spaceships). The mortgage against your house is a Liability for you and an Asset for the Bank, but the house itself is your Asset and no-one else’s Liability: instead, it is part of your total equity.

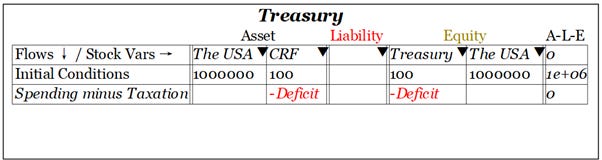

So, what are the nonfinancial assets of the government of the USA? This is the point that Edison alluded to when he said that behind government notes and bonds stood the Government itself, and “who is behind the Government? The people.” Figure 5 illustrates this by showing “The USA” as both an Asset of the Treasury and by far the largest part of the Treasury’s total Equity.

Figure 5: The nonfinancial assets of the country dwarf the government’s negative financial equity

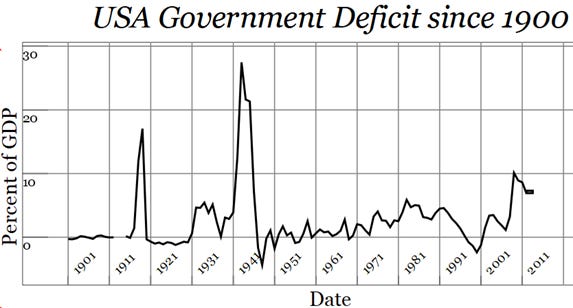

The nonfinancial assets of the government and the country back, and far exceed, the Government’s negative financial equity. Deficit-financed investments, if well-chosen and executed—like the Muscle Shoals project that Ford and Edison were campaigning for—end up increasing the value of the country’s nonfinancial assets as well. This is the reason that the American government can maintain permanent financial deficits: because they’re backed by the nonfinancial assets of the country, which have grown with and because of the deficit over time. Over the last 120 years, the average government deficit has been equal to 2.5% of GDP—see Figure 6.

Figure 6: The US government has averaged a 2.5% of GDP deficit since 1900

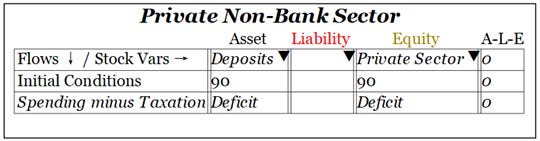

Far from constituting a burden upon the private sector, the deficit eases the private sector’s financial situation. This is the final piece of the puzzle: what does the government’s deficit do to the non-government sectors? As Figure 7 shows, the government’s red ink becomes the private sector’s black ink: the negative financial equity of the government is, dollar for dollar, the positive financial equity of the private sector.

Figure 7: The government’s red ink is the private sector’s black ink

This can be seen in the initial conditions: the private non-bank sector starts with positive financial equity of 90 (Figure 7), and the banking sector starts with 10 (Figure 2). This positive sum is exactly equal in magnitude to the negative equity of the government sectors: the Treasury starts with plus 100 (Figure 4) and The Fed starts with minus 200 (Figure 3).

What about government debt?

How does government debt—really, government sale of Treasury Bonds—change this picture? It does three things:

- It lets the government’s account at the Fed—the “Consolidated Revenue Fund”—remain positive, so long as Bond sales are equal to the Deficit plus interest on outstanding bonds;

- It lets the Federal Reserve maintain non-negative equity, since it has an essentially limitless capacity to buy bonds off the banks in the secondary market. The Asset it accumulates—government bonds—can now match or exceed its liabilities of Reserve accounts and the CRF; and

- It gives banks an interest income which, customarily, they didn’t earn from Reserves, since—before the Global Financial Crisis—The Fed didn’t pay interest on Reserve balances.

This overall system is shown in Figure 8. The Deficit creates money for the non-bank Private Sector; interest payments on bonds creates money for the Banking Sector, in the form of interest on bonds.

Figure 8: The systemic view of government deficits and bonds

This situation is eminently sustainable, so long as the Deficit enables the expansion of the society’s nonfinancial assets. This can include obvious infrastructure projects like the Muscle Shoals hydroelectric plant that Ford and Edison tried to get the government to build (which it ultimately did), and also an educated and healthy workforce. This is what Edison was alluding to when he said “Humanity and the soil—they are the only real basis of money.”

Be the first to comment