With increasingly corrupt state and corporate media, as well as growing inequality, with people having three jobs to survive and little time for politics, democracy is being rapidly eroded. New politics and new media are needed – hand in hand.

Tabe Bergman is an assistant professor in journalism at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University in Suzhou, China.

Western corporate journalism, woefully insufficient from its inception to the present day if you happen to care about the public interest, is dying, and anyone with half a critical eye should say: good riddance! The establishment of non-profit, non-advertising-dependent media funded by money from tax deductions that citizens can directly send to their preferred media organizations could solve many of the myriad current problems facing journalism not just in the United States but worldwide, as radical media critics Robert McChesney and John Nichols have argued in their excellent book The Death and Life of American Journalism.

Yet, though eminently desirable, such a revolution in journalism would not suffice. Rather, reaching a future in which journalism actually brings about changes to politics that make it responsive to the common good, requires the interventions of publics that are economically secure. Increasing inequality is working against this. If the bulk of citizens are too anxious and distracted to pay politics much heed, and thus fail to align themselves with brave new resistance movements, like the Gilets Jaunes in France, critical journalism that exposes the powers that be will continue to not lead to systemic change. These points are rarely if ever made by radical media critics, among whom I count myself, but they are nonetheless crucial.

A brief overview of some intricacies of the academic field of mass communication research is necessary here, as it might explain why radical media scholars have neglected to make the point I am making. Most of them identify with or at least fit into a subfield known as critical political economy of communication, for instance Noam Chomsky, Edward Herman, Robert McChesney, Janet Wasko, Graham Murdock, Herbert and Dan Schiller, and others. This scholarly perspective, a small part of the entire field, quite rightly highlights the dominance of the production side (private ownership, the dependence on advertisers, and so on) of the communication process for understanding the mass media.

Debates raged at American universities in the 1990s between political economists and cultural studies scholars on how audiences fit into such an analysis, with many of the latter emphasizing that ‘ordinary people’ are not inane dupes of the mass media, but have proper autonomous judgment and make conscious decisions about their media use. Many political economists replied by denying that they thought of people as simple dupes, but reaffirmed the great power of the mass media to shape perceptions and beliefs.

Nonetheless, despite holding publics in high regard, political economists tend to pay them little attention. They are not their focus of research and analysis. As far as solutions to deficient media are proposed, political economists focus on changes in policies and laws to make media more accountable to and representative of, if not outright owned and run by, ‘ordinary people.’

Yet a fundamental change in the economic and social position of the public is the only way out of the problems facing politics and media. The point is to change them and the public’s material situation constitutes a missing key.

But, is the public capable and willing to take on self-government?

The work of Walter Lippmann, one of the most influential American commentators of the 20th century, and the responses he provoked and still provokes, are germane here. One of his insights in the seminal book Public Opinion (1922) was to dispel romantic notions espoused by starry-eyed democrats about ‘ordinary people’ – both as to their capabilities to self-govern and their interest in taking on this responsibility.

To Lippmann, the mass of people lack the ability to attend with sustained focus to the important issues of the day, especially, one might add, when these play out far away. The best Lippmann could say about ordinary people was that they are too busy – too absorbed in the mundane details of their own lives – to adequately fulfil their assigned role in a true democracy, namely to keep abreast of the developments of important issues as a basis for public discussions, political participation and voting.

The laundry needs to be done, the kids need to be fed and put to bed – but only after their teeth brushing is monitored. People need to travel to and from work, renew their insurance policies and visit elderly relatives. They need relaxation and entertainment, find partners to date and marry…. the list goes on, as we all know.

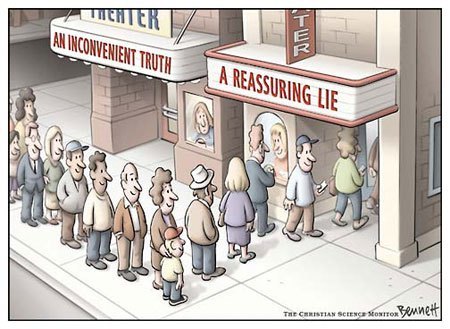

As Noam Chomsky once put it, who has the time or energy to carry out a research project after they come home from work? So people turn on the nightly TV news and think: I guess it’s probably right. Then they plug into the vast reservoir of high-quality mass entertainment, letting themselves dose off while distracted by anything that ignores the bitter realities of today’s world, which they are therefore only vaguely aware of, if at all.

Besides, who wants to be the bore during coffee breaks or at parties by reminding everyone constantly of the threats of global warming and nuclear disaster? That is why many people decide that it is better to keep up with popular entertainment so they have knowledge and opinions of supreme social value: the kinds that connect them with their fellows through banter and shared understanding.

Apart from observing that the public is busy, Lippmann was on occasion distinctly unforgiving as to its intellectual abilities. He spoke of “the bewildered herd.” But, as remarked upon by for instance Chomsky, sports shows demonstrate daily that there is little need to worry: there is nothing wrong with the average person’s mind.

The main problem with Lippmann’s analysis – common in elite political and media circles up to the present day – is that he inferred human nature from human behaviour that, in fact, was to a large extent guided and even determined by a specific type of society: the modern, large-scale, hierarchical, capitalist one. In such a society, many people don’t care about politics, because they lack the time and hold no decision-making power to speak of.

Human nature remains a bit of a puzzle, for sure, one that might never get solved, but there is no reason to assume that, by some evolutionary freak of nature, people genetically just do not care or not enough about the futures of themselves, their families and communities, to pay sustained and intelligent attention to the issues of the day.

The countless acts of resistance from the political left in reaction to neoliberal policies in Europe over the last decades, though they have failed to effect systemic change, illustrate the common-sense assumption that, indeed, people do care. The rise of the radical right, misguided and vile as it is, does also indicate that many people are willing to expend time and effort to engage with issues of public policy. It seems to me that economic insecurity leads a minority to storm the barricades, whereas the majority reacts by ensconcing themselves in front of TV and computer. Economic security for all is likely required before the majority of people will become politically engaged.

It is thus much more likely that the distracted, worried state of contemporary publics is not in-built but the product of political ideologies and economic realities. As radical scholar Michael Parenti observed in a 2012 interview with Carl Boggs: “The 1% does not want a public that is well educated and well informed, free of debt, able to organize and make demands, directed by a strong sense of entitlement and high expectations, advocating not-for-profit social programs and services.”

A key observation in this regard is that publics in social-democratic countries tend to be better informed about world politics than those in authoritarian countries and, more relevant, neoliberal countries like Britain and the US. A study led by James Curran of Goldsmiths, titled ‘Media System, Public Knowledge and Democracy’, concluded that people in Denmark and Finland exhibited higher levels of knowledge of world politics than Americans and, though not by much, the British.

Though this is a complicated issue, it makes sense to assume that the lower levels of inequality and higher levels of economic security, guaranteed for instance by public welfare programs and lower levels of competition in for instance education, that social democracies like the countries of Scandinavia boast, relative to Britain and the US, form part of the explanation. Nonetheless, with Brexit and Trump, things have come to a head to such an extent that many more people in the latter countries now show signs of political engagement than a few years ago.

Here I should emphasize that ‘better informed’ does not equate to well-informed. European media, including the renowned public broadcasting systems, are fundamentally flawed themselves, as I have argued in a book called The Dutch Media Monopoly. They tend to be elite institutions run by elite people, often substantially dependent on advertising income as in the Dutch case, and vulnerable to flak from the political right. They produce news that primarily serves the interests of political and economic elites, not the public’s. My point here is only that, set side-by-side with America’s commercial media, they look a lot less ugly, and impede public understanding less.

Let’s imagine, for argument’s sake, that the western mass media change, overnight, into institutions that actually live up to their espoused values. What would happen?

The basic facts about the corruption and self-serving policies of our economic and political elites, which form a threat to the survival of the planet, would be out there, for sure. Yet, in fact, they already are. The internet provides all of us the opportunity to become truly informed. And as some critical media scholars have noted, for instance Michael Parenti in the interview referred to above, it is quite possible to learn from the mainstream media about the many problems resulting from the social system that is causing so much misery in the world today, with its corporate-led globalization, sham elections, and continual privatization of resources and the public sphere.

Or take the Wikileaks revelations, which threw the inner workings of the American war machine out on the street, for everyone to behold. Or recall Edward Snowden’s revelations on the American and British spying machines. Again, the truth is already out there, but all we got was Donald Trump for president and Brexit.

Once upon a time, in the 1990s actually, many media scholars and other commentators believed that the Internet would solve the problems of western democracies. They have been proven tragically mistaken. If anything, the Internet in its present state acts as a most sophisticated handmaiden to power. A surveillance machine of undreamed proportions, it sucks the tired and anxious masses into an alternate, corporate-sponsored reality of cute cat videos, how-to-get-slim instructions, depoliticized sports, political soundbites and troublesome radical-right ideologies.

Clearly there is a missing ingredient. It seems to me that for the truths already exposed by journalism to actually have the effect of bringing about the necessary revolution in politics, what is required are well-rested publics with the time and peace of mind to fully engage with issues of public importance.

In other words, good journalism matters not one bit until all people possess economic security. People would finally feel confident enough and have the energy to demand the impossible. Chomsky has called global public opinion the ‘second superpower’. I believe this is true, potentially. But we first need to unshackle this superpower from its economic chains.

The solution to the problem of the public’s lack of political participation lies thus not primarily with the media or technology.

The neoliberal policies – which spur on debt, portray every fellow man and woman as a potential enemy and competitor, create anxieties on a scale likely never before seen in world history, and threaten to wreck the entire social system by concentrating money and power at the very apex of society, thereby driving addictions, suicides, escapism and other destructive behaviours through the roof – are the true causes of our misery and lack of ability to engage meaningfully and forcefully with the politics that threaten to destroy us and to challenge the corporate media that often misreport them.

The old aristocrats were right about one thing. Politics is a matter for the economically independent. Not because that is how it should be, but simply as a practical matter. Politics takes time, and guaranteed resources provide time. Money is time. A true democracy is only possible with basic economic security for all. Give publics their dignity and leisure back by providing economic security and they will not disappoint, but will over time successfully demand a journalism that serves their interest, and also transform politics. In short, make all of us gentlemen and gentlewomen and the rest will follow.

Be the first to comment