On November 26th, Yanis Varoufakis appeared on The Jolly Swagman Podcast. For all of us economics nerds, this is the best Christmas present one could ask for. What threw me off my chair was Varoufakis’ opinion on “degrowth.” As a long-time enthusiast of his work, and considering him a pinnacle of erudition and wit, I was surprised to see him fall prey to common misunderstandings. Silver lining: this gives me an opportunity to give degrowth a proper introduction and show that the concept might be more useful that what Yanis Varoufakis thinks.

Yanis Varoufakis responded to this article here

Timothée Parrique holds a PhD in economics from the Centre d’Études et de Recherches sur le Développement (University of Clermont Auvergne, France) and the Stockholm Resilience Centre (Stockholm University, Sweden)

Cross-posted from Timothée’s Blog

Thoughts of future past

“I’m not a degrowth person […]. I’m not one of these people saying that now we need to go back to the bush,” says Varoufakis. It is not the first time I hedge against degrowth being understood as some regressive nostalgia for some distant yesteryear, so I will try not to repeat myself too much. Let me start by saying that there are indeed people who advocate for a return to pre-industrial times, for example anarcho-primitivists. Yet, after spending the last five years carefully scrutinising the idea of degrowth, I can safely say that there is more to degrowth than just that.

The French concept of décroissance (the ancestor of degrowth) has strong existentialist roots, especially in the work of André Gorz. If people can imbue old practices with new meanings, communities should be able to decide which traditions to remember (e.g. agroecology, seasonal diets, hempcrete buildings) and which ones to forget (e.g. sacrifices, patriarchal division of labour, and lynching). This is not a travel to but through the past – becoming aware of many possible modes of existence as to educate our desire for a wider pallet of desirable futures.

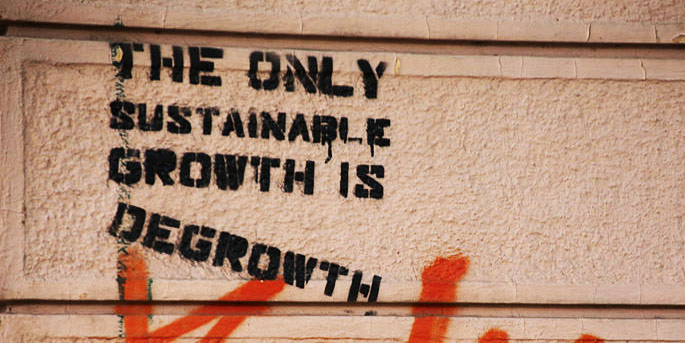

Degrowth criticises a vision of progress which says that whatever is new is necessarily better, and that more GDP is always desirable. The size of a market economy should not be heralded as a universal compass for development, with countries with smaller GDP per capita considered laggards. Perhaps humans are hard-wired to struggle for progress, but what constitute progress is itself an outcome of sociality. We should politicize the concept of progress as to make sure that we can democratically write our own futures. For us revolutionary economists, this means that the future of the economy is not to be predicted, but invented.

Let me borrow from Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia (1951) and say that degrowth starts from the assumption that “[p]erhaps the true society will grow tired of development and, out of freedom, leave possibilities unused, instead of storming under a confused compulsion to the conquest of strange stars.” I like this sentence because, as an economist, I do find the pursuit of GDP strange, especially in situations where it conflicts with concrete social and ecological objectives. If that is so, progress might not only be a matter of new doings, but also of undoing an array of strange practices, like speculating on mortgage derivatives or driving a SUV in Paris.

Gross Domestic Art?

Yanis Varoufakis wants “to see better art, […] more art, more theatres; […] great movies, more Star Trek episodes [and] growth in the care sector, in health, in education,” and who would disagree with him. But I don’t think that economic growth is a means of achieving that. The correlation between GDP and the number of Star Trek episodes might remain a mystery, but we do know that more GDP does not always translate into higher welfare. Finland is famous for having one of the best education systems in the world, despite having a GDP per capita 25% smaller than the United States. Concerning health, Portugal has a life expectancy of 81.1 years, 2.4 years longer than the average American, with 65% less income per person. Icelanders are world first when it comes to cinema attendance and they work 325 hours less per year than Americans – this is enough time to watch 390 Star Trek episodes, every year.

Economic growth is a quantitative phenomenon. Pressing challenges having to do with food, housing, transport, health, art, or education are more of a qualitative nature. If patients need more human contact and care from their doctors, they don’t need an infinitely increasing compound rate of care, but just enough to feel better. Someone who doesn’t have a bike needs one bike – not a yearly rate of 3% in the production of bikes, forever. I doubt Yanis Varoufakis would be happy with more episodes of Star Trek if their quality was horrendous. My point is that GDP growth is a bad compass for qualitative pursuits. This is true for both positive and negative growth. It would be absurd to blindly promote a shrinking of GDP since it would also fail to capture more subtle institutional and lifestyle changes, for example the sustainability of energy sources, the democratisation of the workplace, or the reduction of inequality.

Varoufakis thinks the focus on growth is misguided. “The question is not whether we should have growth or not. What should grow and what should shrink.” The problem is that the pursuit of GDP growth remains – unfortunately – an explicit objective in public governance. One of the Sustainable Development Goals is a growth objective; the European Green Deal defines itself as “a new growth strategy”; the UK even has a “growth duty” written in law establishing that “a person exercising a regulatory function […] must […] have regard to the desirability of promoting economic growth.” This is the situation today. For different institutional reasons, most governments are dependent on economic growth and thus have little freedom in deciding what should grow and what should shrink. One of the objectives of degrowth is precisely to escape this constraining growth treadmill.

Degrowth advocates argue – and they’re not alone – that certain spheres of life should remain outside of the economic logic. I’m sure Yanis Varoufakis would agree with me saying that everyone should be guaranteed access to health and education. (I’m also unsure whether the capitalist logic for-profit competition is any guarantee of better Star Trek episodes.) Market exchanges are only one mode of allocation among at least three others (sharing, reciprocity, and redistribution). On that point, degrowth is not very original and repeats an older critique of economism. This is why I like to understand degrowth as a de-economisation of social life, that is a reduction in the importance of economistic thoughts and practices in society.

Miniature nows and utopian tomorrows

I kept the point that shocked me most for last. “[T]he problem with these crude econometric exercises [I suspect he misunderstands degrowth as a sole decrease of GDP] for the purpose of confirming a Panglossian view that, in the end, we have the best system that we could possibly have.” If I understand him well, Varoufakis assumes degrowth is a mere twitching of today’s economic system, neoliberal capitalism at lower volume. This is inaccurate and it’s worth pointing out because the utopian aspect of degrowth (in the good sense of the term “utopian”) might be its most previous feature.

Degrowth would be a poor concept if it meant the decrease of everything, everywhere, and all the time. Degrowth is not less of the same, but simply different: “the objective is not make an elephant leaner, but to turn an elephant into a snail,” explains the authors of Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (2014). The snail degrowthers envision is an economy with a biophysical metabolism in balance with the living world (hence the downscaling aspect). But it is also a democratic, fairer, and more convivial economy with less inequality and more free time; one that that doesn’t need constant growth in order to remain stable; an economy centred on human flourishing, emancipated from today’s triple growth imperative (GDP for governments, profits for companies, and income for people) and the supremacy of the economic over all other social and ecological concerns. There is much more to say – I actually spent my PhD dissertation “The Political Economy of Degrowth” (2019) exploring the contours of such economy. But I hope these few sentences suffice to show that degrowth is not miniature capitalism but rather a demand for an alternative to capitalism.

Yanis Varoufakis speaks of his “colleagues from the left side of politics [who] keep going on about degrowth, [whichmakes him] lose his will to live.” I have been actively engaging with the degrowth scholarship for the last five years and I find it a precious treasure trove of utopian energy. Degrowthers are as optimists as techno-utopians like eco-modernists and luxury communists, albeit about different forms of innovation and a different agenda altogether. In the twelve years since the concept was translated in English, degrowth has become a thriving field of studies, with almost 400 academic articles, recurring debates, numerous books, and a growing presence in online media (more than 200 essays on the topic in 2020 alone). There is a lot going on, and it is very exciting.

***

I know this was only a 2-min answer to a side question in a podcast. I am here neither to lynch Yanis Varoufakis nor to sell concepts. Varoufakis’ work is not only brilliant but tremendously useful, and I consider him a precious ally in the grand project of deconstructing the hegemony of capitalism. I think this is an opportunity for him, and others who read him, to discover a pallet of progressive ideas that they may have never heard of (to read more, here is a selection of materials about degrowth). Not everything in there is useful, but considering the urgency of the situation and the complexity of the social-ecological crises we’re facing, the more options, the better.

Be the first to comment