Marketisation of higher education in Britain: Many UK university students were cajoled into going to university including expensive tuition and housing costs (both benefiting the university) with the promise of face to face teaching. In quarantine there is not much face to face teaching.

William McGowan is a lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University and works on political violence, survivor activism, and mourning and bereavement.

The non-accident waiting to happen that is campus Covid has gathered worrying momentum, as infection rates climb both on and off university premises with many universities forced to backpedal on their promise to students of face-to-face teaching. Yet somehow despite months of warnings from unions and university staff, who have offered a range of alternative and viable practical and economic solutions to Covid-related problems, students were led back to campuses for the start of term having signed contracts on accommodation earlier in the year. Stranded in new and often unfamiliar towns and cities away from family and loved ones amid local lockdowns, students now find themselves being scapegoated by the same slick business people that were waxing lyrical about providing a world-class “student experience”.

The problems of a heavily marketized education system are more than familiar to those working within it by now, but Covid-19 has revealed this pernicious landscape in greater detail for all to see. If higher education’s (HE) response to Covid in 2020 has often appeared spontaneous, aimless and bumbling, much like the government’s, this belies the very calculated madness of economic reason driving their decision-making. The contradictions that underpin a marketised education system are always there. What we have seen this year is an ongoing attempt by universities to distract people from picking these contradictions apart. Trying to reason or come up with viable solutions can feel futile when it is clear that the fat cats of HE want to decide what will become the “new normal”, not allow the collective mass of staff, students and citizens to potentially envisage a new public university.

Raising concerns about the ignorance, arrogance, and irresponsibility of our university sector in recent weeks has been like trying to reason with somebody who is lost while driving but is too ashamed and stubborn to admit that they have no clue where they are heading. On and on they drive, convinced that travelling miles in the wrong direction is somehow better than conceding defeat, pulling over and consulting with their passengers about how best to get back on track. Before long, they are in the middle of nowhere, all thanks to a futile and costly face saving exercise. If driving metaphors or uncomfortably apt comparisons to the Titanic serve as fitting ways to depict the ongoing incompetency of universities, they also risk trivialising, or at least detracting from, the sheer reckless behaviour of senior management teams and guardians of the upper echelons of higher education who must be held to account for placing profits and their obscene hierarchy above matters of public health. Conspiracy theories aside, at least the sinking of the Titanic was an accident. The same cannot be said of how the pandemic has been handled by the HE sector.

As universities across the UK begin the 2020-21 academic year, casting an eye back over 2020 thus far reveals much about marketisation. The sector’s response to Covid provides an exemplar of how a corporate model of capital accumulation and crisis management now pervades higher education. Decisions which should have reflected, first and foremost, concerns around staff and student safety, followed by adjustments to the pedagogical rationales underpinning teaching and learning strategy, have instead been relentlessly demoted by a university management class hell bent on “business as usual”.

Outlined below is the three-stage process that has played out during 2020, during which time the corporate university has been met with a range of obstacles and challenges. While each stage has seemingly appeared out of nowhere, there is a clever coherence to the strategy.

Stage 1: Closing the Deal

By mid-March the UK had gone into lockdown and it was clear that the pandemic would have some very significant impacts on the sector. Most universities froze any recruitment of new staff, though as many as a third of UK universities had already done this by October 2019, lending weight to the idea that many institutions are likely to have used the pandemic as justification for forcing through further direct reductions in spending. Many calls to extend fixed-term contracts for staff were ignored, meaning thousands of precarious workers faced the prospect of trying to find a job in a temporarily non-recruiting sector – a sector which has increasingly relied on them in recent years, while the salaries of vice-chancellors and senior management have continued to climb. Practical ways to avoid workers falling into financial hardship during this period, such as senior colleagues agreeing to a maximum wage of £100,000 and donating their remaining salary to a hardship fund, were suggested by unions but fell on deaf ears.

As the year progressed, universities quickly realised that student numbers would not be hit as hard as anticipated, quite the opposite. Historically, enrolment at universities often increases during economic uncertainty and recessions as young people find themselves out of work with limited employment prospects. This year saw the same pattern, with added numbers also resulting from the A-level scandal. However, in a spectacular case of putting the cart before the horse, universities and associated private student accommodation businesses quickly capitalised on the “unexpected” groundswell in applications and filled up places as quickly as they could. The effect was doubly worrying for departments up and down the country. Not only did the move exacerbate workload pressures at a time when many employers pursued staff redundancy schemes, but it completely swept aside rising concerns about the safety of staff and students come the autumn and winter. Deals were closed without anything resembling transparent or rigorous consultation.

These quick-footed moves by university economists – seeking redundancy in already stretched departments, getting rid of staff on precarious contracts, freezing recruitment in many areas, ignoring calls to cap excessive pay and signing up higher student numbers to courses and accommodation before it was safe to do so – all look and feel more like the calculated implementation of a shock doctrine-style agenda than bumbling inaction.

The first stage in corporate crisis management doctrine is to assess the financial risks and do whatever you can to mitigate the loss. In this sense, universities have been a law unto themselves. Can you imagine theatres, sports stadiums and concert arenas getting away with saying “let’s just sell our tickets anyway and fill them up”?! At a time when university staff were embroiled in end of semester marking and negotiating the new online landscape, that’s precisely what their universities did ahead of the new term.

Stage 2: Positive PR and Upbeat Communications

As the summer months passed and staff tried to think about how best to plan for the autumn term, the following phase of university contingency planning kicked in. But rather than contingency planning taking the possible shape of online only teaching, surely a logical and prudent step in mitigating the health and safety risks of the coronavirus during the winter months, it became clear that universities were insistent on at least some face to face teaching going ahead. Possible contingency efforts, therefore, were being narrowly channelled into reinforcing this idea with vacuous promises that everything would be OK.

Concerned staff raised all sorts of issues, including the availability of sufficient PPE equipment, the suitability of university buildings for maintaining social distancing, the inevitable difficulties of timetabling on and offline activities for large cohorts of students, some of whom may be in attendance, some of whom may be shielding at home anyway, and a panoply of searching pedagogical questions. What exactly would be the necessary benefits of face to face teaching? If staff would be unable to facilitate traditional group work, discussion and general classroom interaction, how did universities envisage face to face teaching in practice?

Instead of receiving firm answers to these questions, colleagues at many universities have been met with vague and ambiguous proposals, almost all of which seem to be in a perpetual state of preparation. In other words, “we’re working on it”. Indeed, many staff across the sector have been involved in important work to try and ensure a safe and high-quality education for students travelling to live and work on and near our campuses. To criticise the stance taken by the sector is not to detract from this important work. However, instead of listening to such criticisms, many university communications teams have instead promulgated a relentlessly upbeat and totally out of touch stream of positive propaganda, perhaps more reminiscent of authoritarian denialism than higher education institutions. As staff concerns and questions grew, the positive PR approach just grew louder in an attempt to drown out the naysayers, unions and critics of what was clearly becoming a derailed train heading for campus collision come the start of term. In late August, even the Independent Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) delivering an unambiguous warning to universities, calling on them to “focus on providing excellent quality remote learning rather than on opening up campuses that are likely to close again”, did nothing to sway the university juggernaut and was instead brazenly ignored.

Stage 3: Securitization and Scapegoating

The start of teaching this autumn saw hundreds of thousands of students flocking back into cities and campuses to take up residence in their accommodation and halls. The inevitable non-accident waiting to happen has happened and cases have quickly began to rise, with many staff and students testing positive. This rise should not be isolated from broader infection trends which already suggested an increase in both positive cases and, sadly, deaths. Such trends only reinforce the fact that to reopen universities and campuses at this time was clearly madness.

This month has seen the third and most openly hostile response from the corporate university sector in its three-stage process of securing maximum revenue and that has been the blaming, demonization, scapegoating and securitisation of students themselves. Disappointingly, this dovetails with the government’s earlier blaming of a second wave on young people. As the strategies of playing for time and cheerily promising as yet unseen solutions run out of steam, we are seeing universities fall back on age-old tactics used by financial powerhouses to crush opposition through punitive bullying tactics.

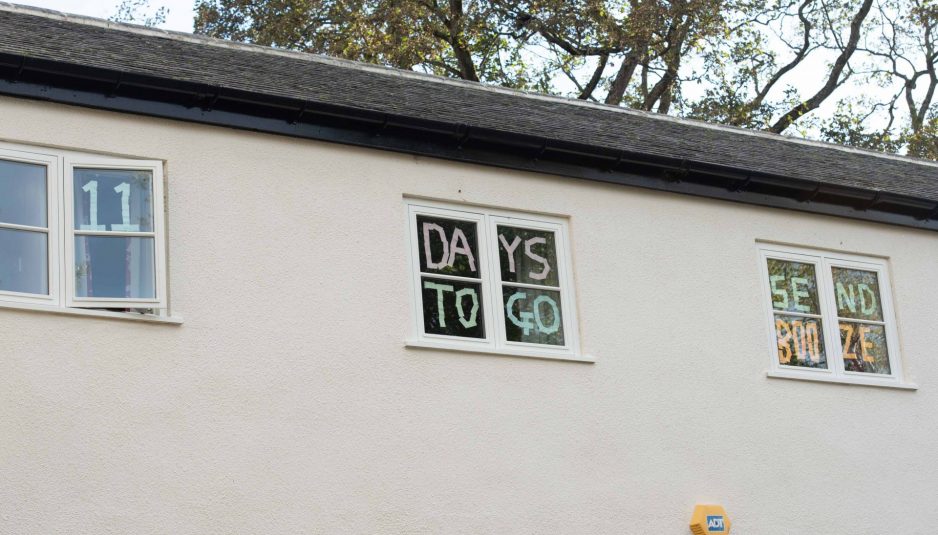

Students were suspended from a number of universities in Northern Ireland for breaching coronavirus regulations and thousands of students across England and Scotland are self-isolating following Covid outbreaks. Thousands more students in Scotland are now to follow strict rules designed to prevent socialising, prompting potential legal action against universities and their “arbitrary use of power”. Students leaving halls in Manchester were met by police and security guards and told that they would not be allowed to return to their accommodation, leaving them feeling understandably “scared and confused”. Being met by reporters and photographers desperately trying to fill front pages has exacerbated this. Talk of a Christmas lockdown which would prevent students from returning home at the end of the semester, while students received welcome talks and induction information online, has left many students questioning why they were encouraged back to campuses in the first place. Of course, students leave home and go to university for all sorts of important reasons aside from their formal education. This does not, however, excuse the appalling actions of our sector.

Public health experts have warned that universities should be two-thirds empty to avoid huge spikes in infection rates. While strict measures to ensure close contact socialising are kept to a minimum are precisely what we need as we head into flu season, the way that universities are scapegoating and responsibilising students is wholly unacceptable. As UCU General Secretary Jo Grady rightly argued, campus Covid outbreaks were “wholly predictable – and predicted”. This is the true contempt the sector has for students and staff. Slogans, strategies, excellence frameworks and student experience promises trip off the corporate tongue, while the truth is that in a marketised education system, much like Monty Python’s poor hospital patient, the staff and students really just get in the way. McEducation is pointing the finger of blame at students as though it has played no role whatsoever in attracting them here in the first place.

Duped?

The UCU General Secretary also pulled no punches when she said categorically that “universities have lied to students.” To claim otherwise is simply disingenuous. Having extorted students for tuition fees and accommodation costs, shaping what are hugely important and stressful life decisions for so many people across the UK, only to lay blame for public health risks at their door, the sector is now complicit in a more general and pernicious attack on young people in this country.

But they have not succeeded in duping them. Marketisation now drives the majority of decisions made by our universities, but they underestimate students’ power and acute awareness of this at their peril (though much to the greater good of higher education). As National Union of Students president Larissa Kennedy rightly points out: “A real worry is that we cannot trust universities to put student and staff safety first, because they are too preoccupied with their position in the market […] They’re committing to in-person teaching, which they haven’t necessarily thought through from a safety perspective because they’re in competition with other institutions. Immunocompromised students and disabled students are once again being erased from the conversation, and of course their staff counterparts.”

It is imperative that we, both staff and students, all stand in solidarity with the National Union of Students and help them to fight back, whether through rent strikes, demands for better mental health counselling services, or calls to refund tuition fee or accommodation costs. These are themselves short-term solutions. The solidarity students have expressed toward striking staff in recent industrial disputes indicates that mutual and collective action across our sector is possible on a much wider scale and that another university is possible. One thing is certain – the “new normal” cannot simply be a continuation of this marketised madness.

Be the first to comment