The EU is being hijacked by the neo-liberal project and must be stopped. That however does no mean that it cannot play an important role in Europe.

Wolfgang Streeck is Senior Research Associate at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne

Image: Markusszy/Creative Commons

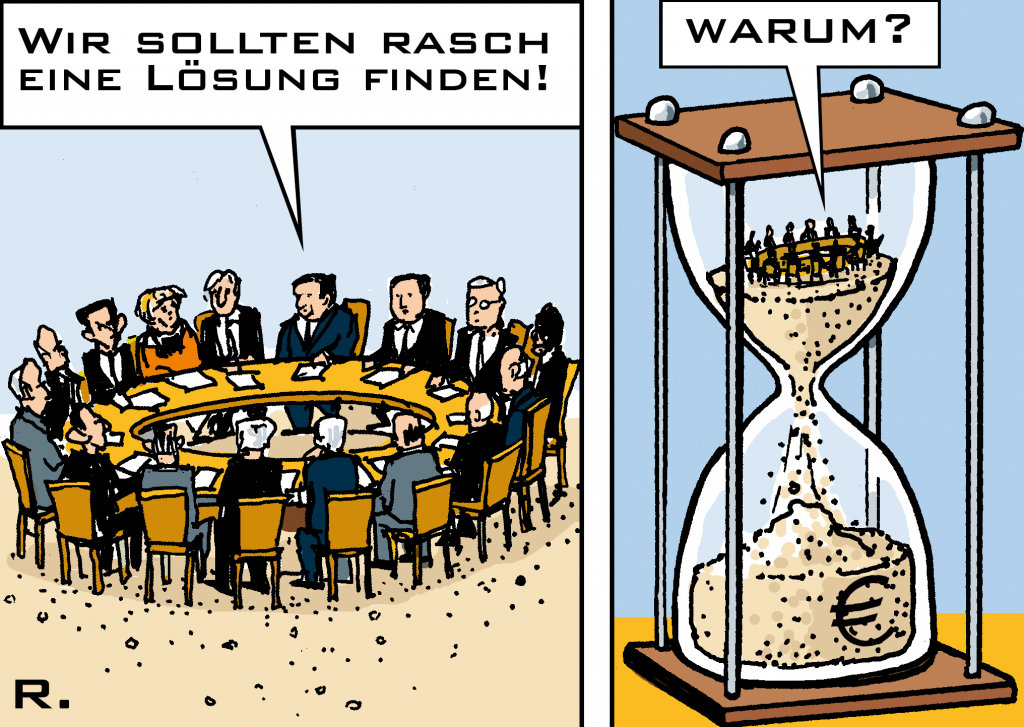

When, if not now, three months before the election of a new EU Parliament, would be the right time to ask what the ever closer union of the peoples of Europe, as habitually invoked in Brussels, should ultimately amount to – what, as the French call it, its finalité should be? Actually, this should be the question of all questions, in Brussels and in the capitals. But although it is always hovering somehow above the conference tables, it is being kept out of everyday business with astonishing virtuosity. This is because any attempt to address it could put an end to the EU-Europeans’ perennial self-deception: namely that everyone imagines the EU to be the same thing, and exactly what they themselves imagine it to be.

The pragmatic exclusion of a problem the inclusion of which would cause dispute over unlaid eggs may be a high political art. However, it is useful only as long as no one disturbs the cartel of silence and the silence does not interfere with pragmatic everyday life. As far as the EU is concerned, however, this point has been reached at the latest with the appearance of more or less “right-wing” opponents who want to know from the administrators of the “European project” in uncouth, but for this reason irrepressible voice what its end result will be. Sticking to business as usual in the face of a swelling chorus like this must appear a serious mistake: pragmatically, because it must further encourage the building of resentment, and democratically, because it damages a democracy if its political class shrouds itself in consensual silence in the face of an increasingly inquisitive public.

Given Germany’s weight in the EU, where the Scholz government is now openly claiming the leading role, it suggests itself to take a closer look in particular at the German idea of the European finalité. What it traditionally envisages is a more or less federalist central state, a “united Europe”, in which the European nation states increasingly become federal states that cede their sovereignty to the federal government under constitutional law or custom and practice, driven by built-in tendencies of centralization, familiar from German federalism, that overcome all formal promises of decentralization. The problem is that this vision is not only not shared by any other member state, but that it is hopelessly outdated given the development the EU has taken in the last three decades.

Of course, this also could be kept secret, which as one would expect the election manifestos of the German-European bloc parties are trying hard. For a while, it seemed as if this could work out – as long as the only dissenting voice came from the AfD, now public enemy number one in state and society, with its abandoned Dexit project. Recently, however, things may have have changed as a new party, Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW), has presented an EU election program which the zealously anti-Eurosceptic German media might find difficult to exclude from political debate – although it cannot be ruled out that they would manage once again to miss an opportunity to bring the German debate on Europe up to date.

To understand the significance of the BSW European program, it seems useful to begin by noting that outside Germany, everyone is well aware that the integrationist German concept of integration has failed, at the latest with eastward enlargement and monetary union. Today, no EU member state puts its national sovereignty up for discussion – as a matter of fact not even Germany itself, which imagines an integrated EU Europe as an upscaled (West) Germany, just as France thinks of its “sovereign Europe” as a horizontal expansion of the French state and, in line with its tradition, cannot do otherwise. The reason why this is so is that today’s EU is far too heterogeneous for any European country, even Luxembourg, to allow its sovereignty to be absorbed into an integrated Euro-state; the German-European ideal of a federal state with a built-in competence escalator is incompatible with the dramatically increased diversity of the states and societies now organized in the EU.

A quick look around shows how deep the cracks are in the EU, which has grown from six to 27 members, or through Brexit: shrunk from 28, cracks that are firmly blocking the path to German-style European integration. In the South, in Italy, despite the country’s decades-long membership of EU and EMU, a prime minister who in Germany is considered a neo-fascist is firmly in the saddle, after the spectacular failure of a series of viceroys sent from “Europe”, from Monti to Draghi, the Super Mario of Brussels, Goldman Sachs and the Frankfurt ECB. In the East, the transplantation of the institutions of post-war Western European democracy is proving as conflictual internally as it is unenforceable from the outside; in the North, Denmark and Sweden remain outside monetary union, and Norway outside the EU; and in the West one of Europe’s three largest countries, the UK, has already exited due to the incompatibility of its politics and constitution with the standard EU model. Moreover, the now second largest member state, France, could soon be ruled by, in German political language, another neo-fascist. Already now, France is no longer available for the much-vaunted Franco-German or German-Franco “tandem” as the informal government of an integrated Europe. Helmut Kohl’s prediction at the end of his chancellorship that the United Kingdom would soon join monetary union and then everybody would quickly move on to political union was just as blatantly misjudged as Wolfgang Schäuble’s lifelong hope that the French force de frappe and Germany’s “participation” in the US nuclear weapons stationed on its territory could somehow be combined to form an integrated European nuclear power.

The fact that a heterogeneous entity such as the EU is ungovernable from above, both technocratically and politically, was demonstrated at the latest after 2008 when Merkel and Sarkozy rescued the German and French banks as a solution to the financial crisis, without being able to move forward to a banking union. A few years later, during the Covid crisis, following the European Commission’s failure to procure vaccines and enforce uniform protective measures with internal borders remaining open, member states quickly switched to taking care of the health of their populations themselves, as best they could in accordance with national conditions. The special “reconstruction” fund of 750 billion euros, debt-financed in circumvention of the treaties, fizzled out without effect. This was especially so in Italy, its actual target country, where Brussels-style national restructuring was to be implemented by Mario Draghi, called out of retirement for the purpose; his term of office as prime minister of an all-party coalition ended with his resignation after just over a year. Nevertheless, there is today talk of a new edition of the fund.

Another policy area in which the EU is unable to reconcile the interests of its member states is and remains immigration. Here, state after state felt compelled to devise their own measures – to speak of “solutions” would be an exaggeration. This includes Germany, which had actually wanted to use the EU to avoid having to deal with the issue at national level. Also, when the Ukraine war broke out the EU found itself excluded from the negotiations between Russia and the United States in the fall and winter of 2021/21, unable to give the Minsk agreements negotiated by Germany, France, Russia and Ukraine a chance. Once the war had begun, the EU was conscripted by the US and NATO to draw up economic sanctions against Russia on the basis of its presumed expertise in economic policy and foreign trade; a year later, the Russian economy was growing while a recession was setting in in Western Europe, and in Germany in particular.

Why do the member states, or more precisely: their political classes, nevertheless cling to the EU, recently even the right-wingers Meloni and Le Pen? In part because they have learned to use the EU as an arena for the pursuit of their national interests, through deals made in the invisibility of the institutional jungle that is the EU system. That system, furthermore, makes it possible to shift national problems and the responsibility for dealing with them upwards, to an imagined European superstate, so as to avoid having to deal with them directly. Moreover, member states can ask the union to dictate policies to them from above that they could not on their own sell to their voters. There also is the possibility, increasingly real, to use the EU as a receptacle for debt taken up, not as national but as collective European debt, which voters would be less apt to disapprove of. And, generally, the imperviousness of the Brussels institutional complex makes it possible to present it ideologically as being on the way, slowly but surely, towards an integrated superstate in which everything will be better: a brand-new ideal state made to order, everything fresh.

It is games of this kind to which a realistically renewed European project with a revised, non-integrationist finalité, as suggested for the first time in Germany by the Wagenknecht platform, would put an end: to the abuse of Community institutions for covert national interest politics, which promotes political cynicism and damages the democratic credibility of member states; to the shifting of responsibility to a democratically inaccessible and technocratically incompetent pseudo-central government, which only exacerbates the problems at hand; and to the spreading of illusions of a completely different future, where what is needed is political institutions whose governors can be held to democratic account. Essential to all of this would be to recognize the central role of nation states in the European state system instead of lamenting it – to refrain from demanding “European solutions” where there can be none; to remedy the “democratic deficit” by strengthening the European role of the parliaments of the member states, instead of calling again and again for more powers for a European parliament that is not and cannot be one – in short, to take seriously the principle of subsidiarity proclaimed in the EU treaties and abandon the illusory hope for an integrated super-policy with uniform super-solutions in a European super-state, designed on the model of the European, in particular the German nation state, only bigger, more beautiful and historically innocent.

The BSW European election program is not a draft European government program, not least because it doesn’t believe in European government. This is precisely what makes it refreshingly original, in particular in the German context: not “more Europe”, which is the stereotypical slogan of all other German parties, but a different Europe: a non-hierarchical, non-imperial, egalitarian community of states, with its international organization providing as a legal framework and institutional platform for nationally responsible international problem-solving partnerships, a Europe of cooperation instead of integration, based on respect for national sovereignty and democracy. There have long been words for this: Europe a la carte, Europe of fatherlands – or if need be, motherlands – or Europe of variable geometry; all frowned upon by Brussels centralists for obvious reasons. If they are to become more than distant memories from a pre-integrationist past, Green dreams of using the EU for the cultural reeducation of insufficiently liberal East European societies would have to be shelved, just as Frau von der Leyen would have to abandon her hopes of one day becoming the leader of a European super-government. Instead, she and her fellow integrationists would have to put up with a European Union turned into a consultancy for cooperation between its member states, assisting rather than governing their collective action, and a guardian of the diversity of interests and ways of life at home in Europe instead of a bureaucratic agency of social and economic standardization.

A EU renewed and, one might add, politically rescued in this way would know that Germany needs a different immigration regime than Greece and vice versa; that Poland wants and needs to work out its own family law just as Germany did, instead of having a “progressive” version dictated to it from above; that Italy needs an industrial policy that suits its economy instead of having to replace it with an economy that suits the internal market, just as France needs a fiscal policy that respects the role of the state in the French political economy, rather than having to put up with a German fiscal regime etc. etc. While at first glance less integration of this kind would look like less Europe, it would clear away divisive political conflicts and government dysfunctions and in this sense would, in effect, amount to more Europe – as suggested by the late American sociologist, Amitai Etzioni, in a chapter on the EU in his last book, Reclaiming Patriotism.

As things stand in the EU, a change in this direction cannot be the result of a Great European Reset, and Wagenknecht’s program wisely abstains from asking for one. What is ungovernable from above is also unreformable from above. In fact, the EU as an institution is structured the way it is in order to make progress towards integration irreversible; where it cannot go forward, like now, it can only get stuck. The good news, however, is that in order to breathe new life into an organization that has fallen out of time, based as it is on the absurd assumption that democratic nation states can be subjected to hierarchical control by an international bureaucracy, no grand master plan is needed. Aware of the ways of Brussels, BSW’s European program, rather than calling for a rewriting of the treaties by a European convention, places its hopes on a persistent push from below, from the member states including Germany, for decentralization and autonomy, returning democratic responsibility to where it only can be effectively enforced: to the national groundwork of the common European house.

Fundamentally what this requires is normalizing in practice and recognizing in theory, rather than denying and denunciating, the movement already under way toward more national autonomy – a movement that Brussels, although increasingly in vain, is still trying to suppress. To stop and reverse centralization, the BSW program advocates something like civil disobedience on the part of member states in the interest of national democracy, where countries allow themselves the right not to follow central directives if they are in conflict with the interests of their voters, not unlike the tried-and-tested French model. For the Left this would among other things mean abandoning the idea of international solidarity practiced through the EU bureaucracy, in favor of direct transnational cooperation between progressive governments and support across national borders for progressive forces in other countries. This does of course not preclude that a future crisis, as could for example arise any time from European monetary union without a European political and fiscal union, might cause so much destruction that a major institutional re-building, or indeed de-building, would be unavoidable.

For the time being, the last hope for a centrally integrated Europe is the transformation of the EU into a military alliance, alongside a protracted war in Ukraine, turning the EU into the European pillar of NATO or even, in a Trump emergency, its successor. Russia would be the external unifier while Germany, as things stand, would unify Europe from within, under supervision by the United States. This too, however, is likely earlier or later to get stuck: the geopolitical positions and geostrategic ambitions of countries such as Poland, Germany and France are too different, and the foreseeable risks and costs are too high especially for the designated field commander and paymaster, Germany. In any case, it is one of the main tenets of BSW as a progressive political party that peace and security in Europe cannot be achieved with a bipolar division of the Eurasian continent and an open-ended arms race along Russia’s western border. To avoid a confrontation between an integrated Western Europe and Russia, BSW suggests a pan-Eurasian security regime based on equal sovereignty of all participating states. Supported perhaps by a revived Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), it would have to be underpinned by agreements on arms control and a broad range of instruments for confidence-building. In fact, by contributing to a Europe of this kind the EU might even return to being the “peace project” that it has for so long claimed to be.

Be the first to comment