Trump doesn’t just want Greenland for the minerals and the glory of territorial expansion, there’s also geo-economic reasons.

Ian Proud was a member of His Britannic Majesty’s Diplomatic Service from 1999 to 2023. He served as the Economic Counsellor at the British Embassy in Moscow from July 2014 to February 2019. He recently published his memoir, “A Misfit in Moscow: How British diplomacy in Russia failed, 2014-2019,” and is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Quincy Institute.

Cross-posted from Responsible Statecraft

Like it or not, Russia is the biggest polar bear in the arctic, which helps to explain President Trump’s moves on Greenland.

However, the Biden administration focused on it too. And it isn’t only about access to resources and military positioning, but also about shipping. And there, the Russians are some way ahead.

Many people look on the map in exasperation at President Trump’s claims that Russian and Chinese ships are a threat to Greenland. Those same people might also forget that the U.S. and Russia are separated in the Bering Strait by only the 2.4 miles between the Diomede islands, and thatthe two countries are much closer together when you stare across the north pole.

The big difference is that while the U.S. has an arctic coastline of 1,060 miles, Russia occupies around 15,000 miles of the Arctic, more than half of the total coastline. Claiming control of Greenland would significantly increase the American Arctic footprint

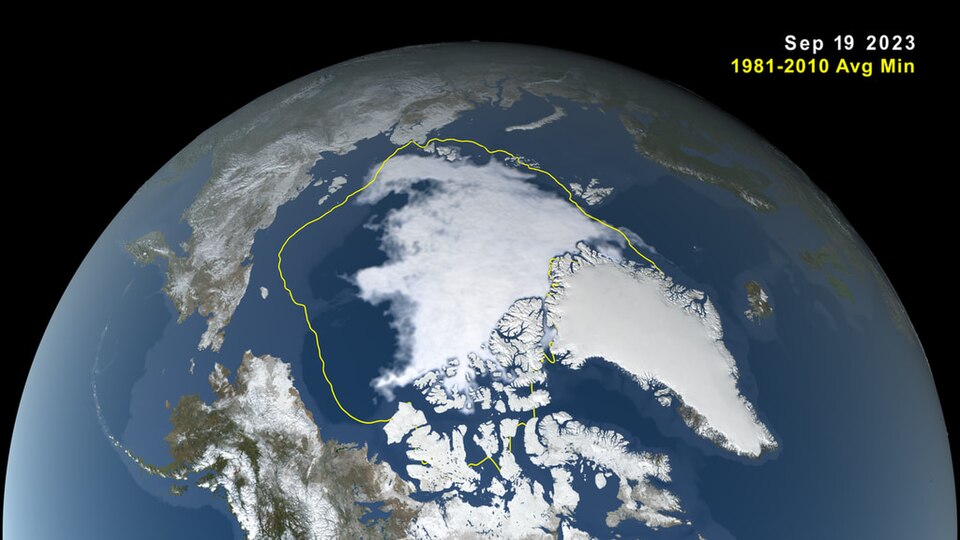

Let’s be clear, tthe Arctic didn’t suddenly appear on the U.S. radar under the Trump administration. The 2024 US Arctic Strategy, published under the Biden Administration, made it clear that the “reduction in sea ice due to climate change means chokepoints such as the Bering Strait between Alaska and Russia and the Barents Sea north of Norway, are becoming more navigable and more economically and militarily significant.”

This sent jitters through the Kremlin, which suggested that Washington was looking for a confrontation to ensure its interests in the region..

Prior to President Trump’s election, Secretary General of NATO Jens Stoltenberg announced that NATO needed to increase its footprint in the Arctic. The accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO helped to do that. Of course, the Kingdom of Denmark is also a NATO ally. But if you think the Biden administration was more well-disposed to Denmark, you might be surprised at the faux pas in the executive summary of the Arctic Strategy in which Denmark was omitted as one of the countries of the European Arctic region.

More than half of the Arctic coastline is in Russian territory and in the past six years 450 new military sites have been built. Russia’s submarine-based strategic nuclear deterrent operates largely out of the Arctic. And while claims of Russian and Chinese co-operation in the Arctic are exaggerated (China is not an Arctic nation, though seeks to lay claim to the region as a global commons) joint military exercises between both countries in the Arctic have increased since the war in Ukraine started.

So, while the new US National Security Strategy spoke of ending “the perception, and preventing the reality, of NATO as a perpetually expanding alliance” the Russians are likely to have fears that Trump’s Arctic ambitions amount to an attempt to encircle from the north rather than the east. And from the US perspective, there remain residual fears that Denmark — unlike the far stronger military nations of Finland and Sweden — would be ill-equipped to defend Greenland from afar. The current U.S. military footprint in the Arctic is small in comparison to Russia’s, and Greenland would help to level that up.

President Trump will also no doubt be focused on the economic value of Greenland, given the supposedly vast natural mineral resources across the Arctic. Some 80% of Russia’s gas and 20% of its oil is currently extracted from its Arctic territories. Greenland is thought to house the majority of raw materials deemed critical for electronics, green energy and military technologies.

But it’s on the high seas that President Trump may also see considerable benefit in Greenland and here Russia is a long way ahead. Since at least the start of the Ukraine crisis, and with global warming making the Arctic increasingly navigable by sea during summer months, Russia has been actively developing its Northern Sea Route. Going over the top of the world slashes the distance for ships traveling between Europe and East Asia by three times, halving sailing time, compared to routing through the Suez Canal.

Russia also exerts complete control over the Exclusive Economic Zone that it passes through.

The comparable Northwest passage, over the top of Canada and Alaska, is seen as potentially shaving almost 3,500 nautical miles off the shipping routes for cargo that might normally transit the Panama canal. In 2013, the bulk carrier Nordic Orion made the journey from the eastern U.S., saving four days sailing and £200,000 in the process.

However, the legal status of the North West Passage is long disputed between Canada, which claims it as internal waters, and the U.S. American control of Greenland would radically change the balance of power and control over the route, with the U.S. anchoring both choke points, in the Bering Sea and into the Atlantic.

A less legally contested North-Western passage would also make it easier for the U.S. to maintain unchallenged military navigation across one half of the arctic waters. Gaining Greenland would make the U.S. both the entry and exit point to the route, reducing the strength of Canada’s claim to exclusive control.

Right now, relations between Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney are strained. Pushing the issue of Greenland may be a tactic to pressure the restive Canadians into a deal on use of the route. Trump’s trolling of the Canadians with an AI image of the Oval office and a map in which the stars and stripes covers the territory of Canada must be seen in this light.

For now, the shadow boxing over Greenland seems set to continue, with the Trump administration putting pressure on the Danes to settle a deal amicably. With Greenlanders possessing the right to self-determination from a 2009 Act on Self-Government, the Danes are not standing on terra firma legally. But let’s be clear, when Trump talks about Russian ships near Greenland, he probably means those with cargo as much as those with cannons.

Be the first to comment