Is it envy or justice?

Branko Milanović is an economist specialised in development and inequality. His new book, The Visions of inequality, was published October 10, 2023.

Cross-posed from Branko Milanović’s blog Global Inequality and More 3.0

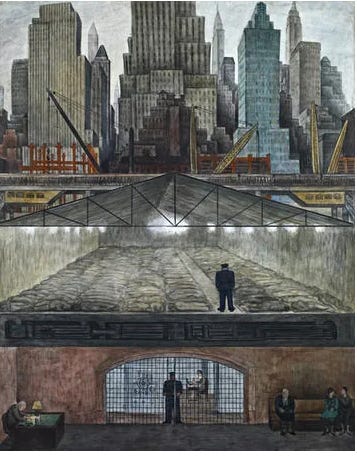

Diego Rivera, Frozen Assets (painted in 1931).

[A very long read. See the explanation below.]

Many economists dismiss the relevance of inequality (if everybody’s income goes up, who cares if inequality is up too?), and argue that only poverty alleviation should matter. This note shows that we all do care about inequality, and to hold that we should be concerned with poverty solely and not with inequality is internally inconsistent.

A common argument made by some economists is that concerns with distributional matters are irrelevant—or worse, pernicious. Distributional matters are often viewed as a distraction, a nod to populism, and a waste of time that is ultimately destructive: A fight about the slices of the pie reduces the size of the pie and makes everybody worse off. Such activities, even a discussion about them, are regarded as negative; how much better to focus on hard work and investment and to make the pie grow. Two well-known economists have recently made such points. Martin Feldstein in the opening address to the Federal Reserve conference on inequality (1998a, 1998b, and virtually identically in Feldstein 1999) writes that no one should be worried about inequality, so long as everybody’s income is increasing: “I want to stress that there is nothing wrong with an increase in well-being of the wealthy or with an increase in inequality that results [solely] from a rise in high incomes” (1999, 35–36). Robert Lucas, in the 2003 Annual Report of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, writes: “of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion, the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution” (Lucas 2003).

In its more or less sophistical form, this is an argument not infrequently heard. As someone who has worked on the issues of inequality for more than twenty years, I have had a chance to hear it expressed numerous times. In the early 1990s, a highly placed World Bank research economist dismissed my proposal for a study of inequality in post-communist countries, arguing that these countries were “victims” of unreasonable egalitarianism, and all increases in inequality, linked as they must be to higher returns to more productive members of society, should be welcome. Four or five years later, with the greatest recorded peacetime increase in poverty, and with inequality increasing by leaps and bounds, the subject did not seem so unreasonable. In many social parties or professional meetings in Washington and elsewhere, when introduced to and informed that I worked on inequality, my (more polite) interlocutors would make a point similar to Feldstein’s (“Why should inequality matter at all?”). Others, perhaps less polite, would wave their hands, basically ascribing the fact that anyone would pay a person to study inequality to profligate ways of international bureaucracy.

I will allow myself to speculate at the end of the note why the topic of inequality produces such strong reactions among many people from various lands and backgrounds. But first, I will try to make a few more substantive points, limiting myself to not making pro-equality arguments of two kinds. First, following Feldstein, 1/ I, too, will eschew to base my case on the functionalist arguments in favor of low inequality, whether they be of the median-voter kind, social instability (with attendant low investments), perversion of political process, market failure, or any other type. Two recent excellent reviews (Eric Thorbecke and Chutatong Charumilind, “Why We All Care About Inequality”, World Development, September 2002, and Christopher Jencks, “Does Inequality Matter?” Daedalus, Winter 2002) summarize, analyze, and assess the effects of inequality on a wide range of economic and social issues. The reader should be simply aware that there are functionalist (or instrumentalist) arguments in favor of complementarity between equality and efficiency that are as strong as, and arguably stronger than, the opposite arguments, which see the two (equality and efficiency) as a tradeoff.

A second type of argument I will not make refers to the attempts, tacitly present in the quotes and the tenor of the argument cited above, to eliminate from the political debate an issue as important as distribution. Surely this is unlikely, since the problems of distribution have been at the center stage of political struggles from time immemorial. But one nevertheless detects an unpleasant impatience in some economists who would like such topics to be expunged from politics. In other words, I will not use the argument that these economists thereby display rather unpleasant authoritarian or, to be charitable, paternalistic traits.

Is It Envy or Is It Justice?

Consider the example given by Martin Feldstein (1999) of a group of well-heeled economists gathered at a conference or subscribers to an economic journal. If each of us—the economists—were given $1,000, inequality (in the United States) would go up; each of us would be better off and no one would be worse off. So what is wrong with this? asks Feldstein. Apparently, nothing. Let us now modify his example just a bit. Let us suppose that Feldstein’s fairy gives me $20,000, and each of the other participants is variously given between 25 and 75 cents. Feldstein’s previous conclusions still hold: everybody’s welfare should be greater. Yet, the effects, I dare to suggest, would be quite different. Many of the participants might refuse to accept their quarter, some might leave it in the room, others throw it away in disgust. Many would comment (unfavorably) upon the fact that I have received, for some unfathomable reason, $20,000, while other, much more worthy members of the group, would have to do with less than 1/1000th of that amount. Most would speculate on the reasons that lie behind such extravagant largesse on the part of the fairy.

What does this story illustrate? First, that many (most?) of those who would have received 25 cents would not merely not feel better—as Feldstein suggests they should—but would rather feel worse. They would feel worse off because their feeling of justice and propriety would have been hurt. And it will have been hurt because people always compare themselves to (what they hold to be) their peers. Thus income they receive is not only a means to acquire more goods and services, it is also a tangible recognition of how society values them. It is a social expression of their own worth. Hence a large difference in income (and particularly if unjustified or unclear) will be viewed as a slight to their own worth.2/

The key point is that income of others enters our own utility function. And once we allow for it, inequality affects our own welfare and the arguments regarding irrelevance of inequality come to naught. Note that the concept of a peer group is crucial for all studies of inequality. 3/ There is no point in studying inequality between two groups that do not interact or that ignore each other’s existence. Suppose we combine all Japanese and all Maya of the fifteenth century and study their combined inequality. The two groups might overlap quite a lot, their mean incomes being similar. But this exercise is devoid of any meaning since the two groups have never interacted. It is only when a nation-state appears and people begin to view their co-citizens as their equals that conventional studies of within-country inequality begin to make sense. This is why studies of global inequality make sense now, but much less so for the earlier periods. In other words, only if there were no peer groups—that is, if there were no society—would inequality be irrelevant and would only our own income matter for our welfare. 4/ In a solipsistic world indeed we (I?) need not bother about inequality. But in all other worlds, we (I) would.

But let me try to find some other, perhaps, more convincing examples.

Let us assume that, for the same economics conference, the organizer has decided to pay each of the participants a fee reflecting his or her position in the profession and thus the expected quality of the paper. And let us assume that such honoraria are widely skewed but are all, of course, positive. Let me now assume that I, among all of the participants, got the least, and by a large fraction. Would this not affect my own sense of justice? I would quickly begin comparing fees received by other authors to their published record or to what I have heard of them. I would inquire from my friends, and I might end up being deeply offended. Again, my feelings of (1) justice and (2) self-worth would be affected. In the first example, many people might dismiss in disgust their quarter of a dollar. In this case, I would accept my honorarium but would be quite upset and perhaps offended. Even if my welfare is greater after the honorarium (because my income would be higher), it will have increased far less than if everyone had received the modest fee that I got, or if the fees were more in line with what I perceive to be just. And again, once we accept the fact that my welfare is reduced by the knowledge of how much other participants received, we conclude that other people’s income enters my utility function, and thus that inequality matters. If this were not the case, how would we explain the fact that in the ultimatum games, where participants are asked to share an amount of money, offers perceived as unfair are rejected out of hand, and both people end worse off (Fong et al. 2003). 5/ Why do people reject offers they hold unfair if thereby they reduce not only the income of the other participant but their own, too? Simply because the utility gain from higher income is outweighed by the utility loss caused by the feeling of injustice stemming from the realization that the other person would receive a much greater and, in our view, undeserved income. But clearly we should never behave like that if we were unconcerned with the incomes of others.

Notice that in all three examples, we have shown that people’s welfare depends on the income of others, but that the mechanism by which this is expressed varies. In the first (“the good fairy”) example, we were puzzled by the capriciousness of the fate; in the second example (“the fee”), we called upon justice; in the third example, we were simply disgusted at the behavior of our partner—neither justice nor fate entered there: pure human disgust or anger.

More Arguments

Some economists tend to regard all statements that other people’s incomes influence our welfare as statements of envy. Martin Feldstein writes of “spiteful egalitarianism.” Two points are worthy of note here. First, ethics is not the province of economists. The use of value-laden terms like “envy” is supposed to shut us up by basically telling us that only green-eyed envious monsters are likely to covet other people’s money. Let us grant this point: envy is not nice. But if most, many, or a significant percentage of people do feel envious of other people’s money, this is the only thing with which economists need to concern themselves. (And recall that envy simply means that other people’s income enters our utility function.) Envy, whether economists approve of it in private or not, must be part of their analysis. Perhaps ethicists and religious ministers would disprove of such practices, and we leave the field open to them to improve the human race. When the ministers have done so, economists should go back to revising their assumptions and wiping out income of others from individuals’ welfare functions. But not before we are informed that envy has been rooted out.

Second, what some people call envy is, as I believe the above examples have shown, not (the bad) envy but (the good) sense of justice. We are affected by income of others not solely because we are envious but because we think that injustice has been done. It is that we feel that somebody has been taken advantage of, or has been treated unfairly. In other words, behavior that in the eyes of some may be construed as envy may in reality be motivated by justice. One person’s envy is another person’s justice. Consider the recent example of land reform in Zimbabwe, and leave aside the arguments whether land reform will help productivity or be detrimental to it. Those against it will argue that the movement is motivated by pure envy; those in favor of it will view it as a way to redress the old wrongs. But under whatever name these motivations and feelings come in, whatever rubric we write them in (“desirable “ or “nondesirable” feelings), they can be shown, I think overwhelmingly, to exist, and that is all that matters to people who deal with human nature as it is. Let me close this section with two quotes that illustrate very well the difference in economists’ views regarding inequality. First, a fairly recent quote by Anne Krueger (2002), former deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund: “Poor people are desperate to improve their material conditions in absolute terms rather than to march up the income distribution. Hence it seems far better to focus on impoverishment than on inequality”—a position echoed by Martin Feldstein and Robert Lucas. And then the one by Simon Kuznets (1965, 174), an old quote from 1954:

One could argue that the reduction of physical misery associated with low income . . . permit[s] an increase rather than a diminution of political tensions, [because] the political misery of the poor, the tension created by the observation of the much greater [income] growth of other communities . . . may have only increased.

Why Don’t People Like Studies of Inequality?

When I started working on inequality, I lived in a communist country. My dissertation was on the topic of inequality—what was then euphemistically called a “sensitive topic.” The rulers and their acolytes did not like it because it exposed their myth of universal equality under socialism. They wanted socialism to be perfect and equal, and it was shown to be imperfect and unequal. When I came to live in a capitalist society, rich people (and their supporters) similarly tended to object to the topic. They felt that any inequality that existed was right, since in their view every income was fine, just, and necessary, almost God-ordained—market having taken over the role of God. Empirical studies were superfluous. The studies could merely sow trouble and discord and possibly lead to questioning of the existing social order. Thus the elites in both systems tended to agree that studies of inequality are unnecessary: in one case because they revealed that there was inequality, in the other because they implicitly questioned whether its level was acceptable. But such great sensitivity toward empirical work on inequality shows that our implicit assumption, probably derived from centuries of religious upbringing and the Enlightenment, is that all people are basically the same and that it is every departure from equality that needs to be justified. 6/ Even within the confines of utilitarianism and identical and concave welfare functions, there are two reasons for censuring inequality, writes Sen (2000, 67): it is inefficient as a generator of utility (since some redistribution toward the poor would rise the overall level of welfare), and it is also iniquitous. In other words, the elites are not unreasonably concerned about studies of inequality every mention of inequality raises in people’s minds questions about its acceptability.

Why Is Caring About Poverty and Not About Inequality Implausible?

If inequality were not something we cared about, it is also very difficult to explain the concern with poverty. For if (1) all incomes are just, or if (2) other people’s incomes do not enter my welfare function, why should I care if there are many poor people? Or even if only (2) holds, why should the existence of poverty matter to me? A person might reply that one might still disapprove of studying inequality but find that the welfare of the poorest could be of concern since we hold that everyone should be endowed with some minimum standard of living. But if this is the case, is this not equivalent to saying that it is only the welfare of some (viz., the poor) that enters my utility function and nobody’s else (except mine or my family’s)? So a proponent of concern with poverty does not disagree that other people’s incomes enter his utility function; he just wants his homo economicus to limit his attention to a group of people (the poor) and to disregard others. The inconsistency of a position that cares about poverty and does not care about inequality is readily spotted if we think that it implies that in a person’s welfare function, there is a place only for his/her own income and for people with low incomes (the poor).

To say that one cares about poverty means that his welfare function is affected by everything that happens below some arbitrary income level where the poor dwell, while any income change above it (except if it affects his own income) leaves him indifferent. This scenario, of course, is not entirely impossible, but seems to me quite implausible. As soon as we extend our gaze toward other people, richer than us, and let their incomes influence our own welfare, too, we move from concern with poverty alone to concern with inequality as well.

To reinforce the argument in favor of this rather implausible concern with poverty only, a moralistic gloss is put over it whereby the concern for all incomes less than some poverty level is deemed “good” since it shows a person to be concerned with the plight of the poor, while his concern with all incomes greater than his is deemed to be morally reprehensible. In reality, however, people are much more likely to think about and be concerned with those who have more than they than with those who have less.

In other words, it is “envy” that is much more likely to enter our welfare function than “concern.” I would be willing to venture an even stronger statement: that a very different treatment of poverty and inequality favored by some economists, a sharp distinction drawn between the two, is a way of deflecting the possible raising of the issues of social desirability of a given distribution of income into a much more benign channel: ostensible concern with the very poor.

The concern with poverty is a price that the rich are willing to pay so that no one questions their incomes. In other words, the concern with poverty works like an anesthetic to the bad conscience of the many. For many of the rich, helping the poor is “social money laundering,” an activity engaged in by those who have either acquired wealth under dubious circumstances, or have inherited it, or might have made more money than seems socially acceptable. 7/

It could well be that less than savory ways of acquiring wealth are unavoidable and that this is the price we have to pay for progress and civilization. “A world without poverty” is a world that would underwrite all kinds of injustices. Unavoidable it may be—but it still should not stop us from recognizing it for what it is.

Explanation

This is the text of my article published in Challenge Magazine, vol. 50, issue 5, 2007. Recent discussion about inequality between David Lay Williams and Don Boudreaux reminded me of it and prompted me to bring it back to life (esp. given that the journal where it was originally published no longer exists). My piece was written around 2003 when I worked at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. It was prompted by what I heard Martin Feldstein say at a conference on poverty and then repeat in his writings. The article was rejected by several economics journals to which I sent it to be published in their Notes sections. I was especially disappointed to have been rejected by the Journal of Economic Inequality which even had a section that was a natural venue for such broader discussions of inequality. The article was first published in the Italian translation by La Questione Agraria, No. 4, 2004. Several years later when I mentioned it to Jeff Madrick who was then the editor of Challenge, he asked me to send it to this journal. It was thus ultimately published there in 2007.

Notes

1. “In rejecting the criticism of inequality per se, and in asserting that higher incomes of the well-off are a good thing I am not referring to the functional arguments that some have offered in defense of inequality” (Feldstein 1999, 35).

2. It is an intriguing language point that one would have expected that the correct question in English regarding a person’s wealth would be “How much are Mr. X’s assets worth?” This, however, is abridged to “How much is Mr. X worth?” The intrinsic worth of the individual and his extrinsic wealth are conflated.

3. The same point is made by Sen (2000, 64), who uses the concept of the “reference group”: “the focus [of welfare measurement] is on the utilities of the individuals only in that group, without any direct note being taken of the utilities of others not in the group.” A similar conclusion, based on empirical happiness studies, is reached by Frank (2004, p. 72). Recent happiness studies have uniformly found that, at any given point in time, happiness increases with income (“money buys happiness”). Yet, over time and despite much higher income of all—the poor, the middle class, and the rich—happiness does not change. The implication is that t is relative, not absolute, income that matters for happiness. But if that’s the case, then clearly our position in income distribution affects our utility much more than absolute level of income.

4. A nice example of how peer groups matter is the following: The World Bank has many local offices in different parts of the world. Staff members who are recruited to work there are generally paid much more than their local peers. So they are very happy to work for the World Bank. But, after a few years, they realize that they are paid only a fraction of what an identical economist is paid if hired by the headquarters in Washington. Then locally recruited staff become very unhappy and demoralized, their peer group having changed.

5. In the ultimatum game, two people are supposed to divide a given amount of money. Person A makes a proposal. Person B accepts it or rejects it. If he rejects it, other participants receive nothing. Overwhelming experimental evidence shows that offers amounting to less than 30 percent of the pie are rejected. The experiments have been conducted in a number of countries and settings with stakes as high as three months’ earnings (quoted in Fong et al. 2003, 8).

6. The statement “basically the same” represents an oversimplification, for once we ask in what way people are not all exactly the same, we open the doors to unequal incomes. As Sen (1979) argues, observed inequality in income could be justified on utilitarian principles (maximization of total welfare), difference in initial conditions (e.g., if equality of total utility per person is our objective, then a handicapped person should get a higher income than a healthy one), or, more broadly, human diversity, which, to provide each with the same capability to do certain things, requires that incomes be differentiated. However, note that in all these cases, the “sameness” of people refers to (1) our acceptance that the same rules apply to all, and (2) that the objective of each rule is equalization of people’s conditions (however the latter are defined). The equalization of conditions can, and most likely will, entail differences in incomes. How does it differ from the Pareto principle? There is no attempt in the latter to equalize anything: the initial income or endowments are given. In other words, the rules do apply equally to all, but point (2) is not present.

7. It is historically true, of course, that some of the people who have acquired their fortunes under (to say the least) dubious circumstances have used them for philanthropic purposes. While it is certainly preferable that a part of such vast fortunes be used thus—even when we disregard the self-interested element of tax avoidance—it still raises an uncomfortable feeling of accepting an alleged moral superiority of people (“philanthropists”) who in their working lives were far from paragons of ethics. I could thus never feel anything but disdain for “capitalist lyricism” to which hapless strollers along Fifth Avenue in New York are exposed when they come to the Rockefeller Center. I can understand that with your own money you can build a monument to yourself in your own backyard, but not in the center of a world metropolis.

Be the first to comment