![]()

When Donald Trump recently announced tariffs on steel and aluminium imports he was condemned by proponents of free trade across the world. His critics said the US president had not understood how protectionist policies would spell disaster for the world economy. Fair enough. But this is the same Trump whose decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement also met with massive disapproval.

Trump is simultaneously chided for refusing to cut emissions, and for promoting a trade policy that reduces the causes of such emissions. Both sets of critics may be right on their own terms, but the contradiction between the two reproaches exposes big problems in the mainstream modern worldview. Is it really reasonable to advocate for both more trade and greater concern for the environment?

For centuries world trade has increased not only environmental degradation, but also global inequality. The expanding ecological footprints of affluent people are unjust as well as unsustainable. The concepts developed in wealthier nations to celebrate “growth” and “progress” obscure the net transfers of labour time and natural resources between richer and poorer parts of the world.

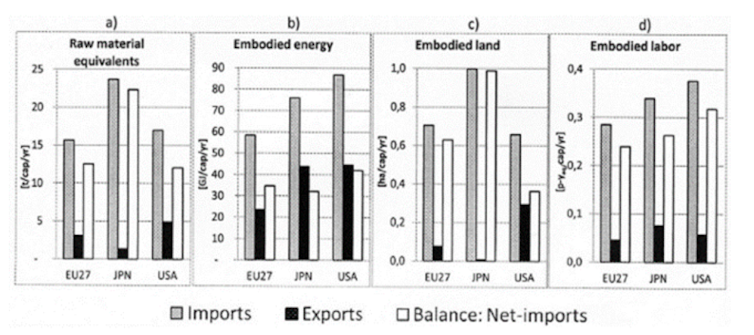

Dorninger and Hornborg, 2015, Author provided

For instance, the household of an average American couple with one child has the equivalent of an invisible servant working full time for it outside the nation’s borders, while the average Japanese household with one child uses three hectares of land overseas. Yet such material asymmetry appears to be a side issue for mainstream economists, who continue to assert the overall benefits of free trade.

This same ignorance is particularly apparent in the fight against climate change. Most environmentalists and researchers put their faith in new technologies for harnessing the sun and wind, and hope that politicians can be persuaded to act. But solar panels and wind farms are not merely products of human ingenuity that have been revealed to us by nature. Nor are they magical keys to limitless energy.

Renewable energy technologies emerged in this specific human society – inequality, globalisation and all – and their very feasibility is dependent on world market prices. Like other modern technologies they depend on high domestic purchasing power combined with cheap Asian labour, Brazilian land, or Congolese cobalt.

bmszealand / shutterstock

Almost 50 years ago the ecological economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen warned that the notion that solar power could replace fossil energy was an illusion, because it would require such enormous volumes of materials to harness the requisite amounts of diffuse sunlight to satisfy a modern high-tech society. Some of these materials are rare and expensive and degrade the environment. Moreover, the United Nations Environmental Programme recently warned that the world is heading for ecological disaster unless we use less resources per dollar of economic growth.

The Czech-Canadian energy researcher Vaclav Smil has found that switching to renewable energy would use up vast amounts of land, reversing the land-saving benefits of the Industrial Revolution. Meanwhile the money to invest in solar is still ultimately generated from cheap labour and cheap land. The fact that solar panels have recently become less expensive is partly because they are increasingly being manufactured by low-wage labour in Asia.

When viewed this way it is perhaps no wonder that renewable energy has not even begun to replace fossil energy, and has only been added to the still-increasing use of oil, coal and gas. Solar power still only accounts for about 1% of global energy use. It has hardly made a dent on the global use of energy for electricity, industry, or transports. And this cannot be blamed on the oil lobby, as is illustrated by the case of Cuba. Nearly all of the island’s electricity still derives from fossil fuels. There is obviously something problematic about shifting to solar power that goes beyond corporate obstruction. To explain it in terms of a lack of capital or in terms of the vast land requirements are two sides of the same coin.

So here is the impasse of modern civilization: the free trade promoted by most economists and politicians continues to drive a substantial part of the greenhouse gas emissions that they want to reduce, and yet the sustainable technologies they propose to cut emissions are in themselves dependent on economic growth, international trade, and the use of more and more natural resources.

So how to break this impasse? Economists could start by recognising that the economy is not insulated from nature, just as engineering is not insulated from world society. Global challenges of sustainability, justice and resilience all demand much more integrated thinking.

This will involve confronting conventional ideologies of technological progress and free trade. Rather than nervously safeguarding world trade with its escalating greenhouse gas emissions, we have every reason to reconsider what might be perceived as true human progress and quality of life. Instead of economic policies maximising economic growth and resource use, humankind needs to develop an economy that is aligned with the constraints of our fragile biosphere – and a science of engineering that takes account of global inequalities.

Alf Hornborg, Professor of Human Ecology, Lund University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Be the first to comment