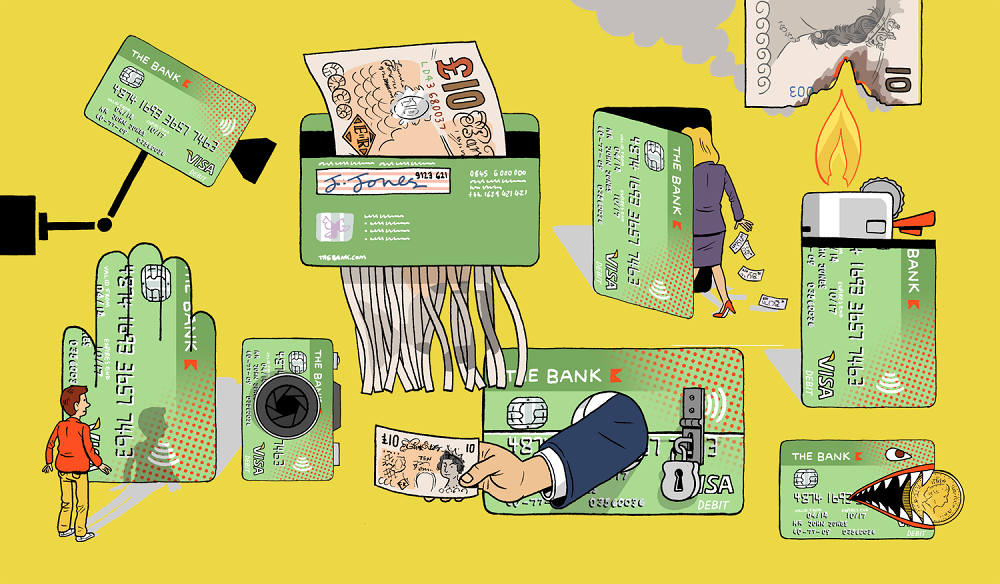

While science suggests that PIN pads are more dangerous than cash, the retail sector continues to spread fear about it. Is this just a naive mistake, or are there darker motives?

Brett Scott is an author, journalist and financial campaigner. He tweets as @suitpossum, and makes videos about monetary systems and the war on cash here

This article cross-posted from Positive Money but first published on alteredstatesof.money

In early March 2020, the World Health Organisation emailed a journalist to say ‘We did NOT say that cash was transmitting coronavirus’. This angry rebuttal came after the British Telegraph newspaper misrepresented them as being anti-cash. Days later the head of Germany’s Robert Koch Institute for infectious diseases said “(Virus) transmission through banknotes has no particular significance”. He was followed by the German central bank, who put out a release saying ‘Cash poses no particular risk of infection for public’, noting that “the probability of becoming ill from handling cash is smaller than from many other objects used in everyday life”. They were followed in April by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), who noted that “Scientific evidence suggests that the probability of transmission via banknotes is low when compared with other frequently-touched objects, such as credit card terminals or PIN pads”.

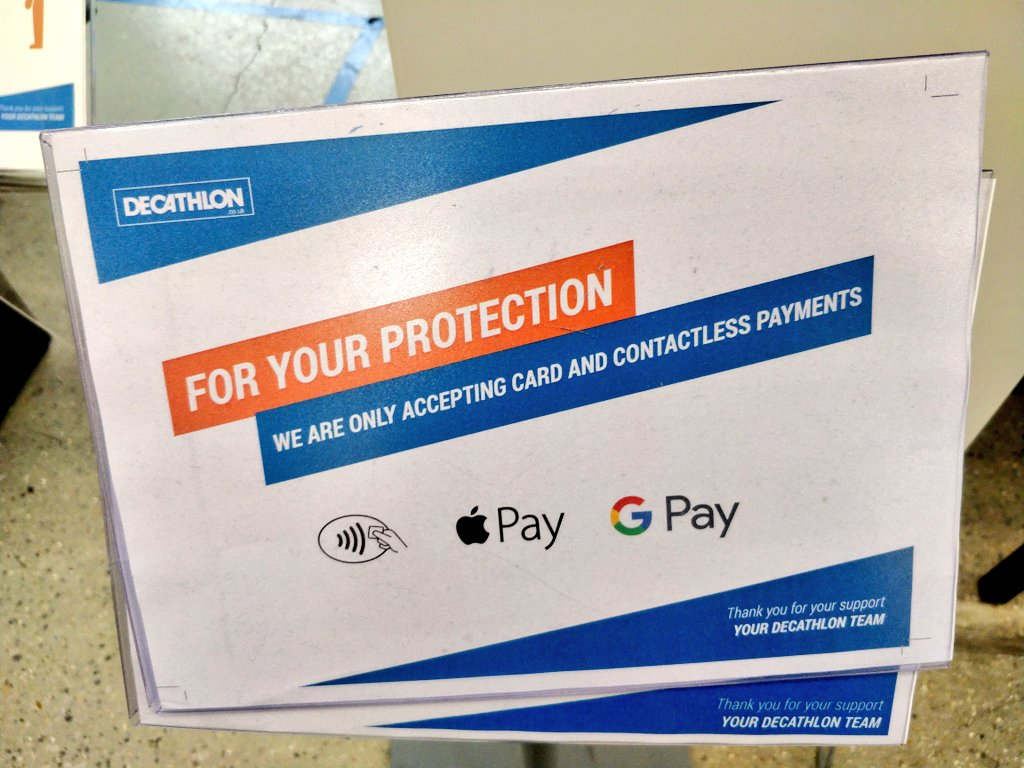

Why then, am I confronted by signs like these?

Decathlon, where I took this photo, is a large sports chain store where people frequently make purchases over the contactless card limit (buying medium value items like running shoes, tennis raquets, and so on), which means they are telling people that pressing PIN pads (used by hundreds of others) is for their ‘protection’.

They are not alone. Almost every large supermarket chain in the UK is doing this. When I’m in Morrison’s – a large UK supermarket chain – I am asked to pay by card over a loudspeaker: the unscientific consensus in all these major stores is – cash is dangerous. More dangerous than using card terminals or pushing the buttons on the screen of our self-service checkout counters that thousands of others have used.

Perhaps the concern is not so much for customers as for staff, who might have to handle cash handed to them by hundreds of people. Let’s be real though. Their check-out staff are handling thousands of items handed to them by hundreds of people who take them off the shelves. It’s not like cash is uniquely risky for their staff in this situation.

This practice in supermarkets is extremely worrying. During the early days of strict lock-down, they were among the only institutions allowed to stay open. The entire population of the UK would scurry out of their homes to nervously enter these stores, all of which decided to start broadcasting anti-cash messages to these anxious customers, despite the fact that major institutions like the WHO and BIS rejected the claim.

The War on Cash

At best this anti-cash stance is well-meaning but misguided and irresponsible. At worst it’s a push to force people to use digital payments for profit-seeking reasons, disguised as a concern for public health. For the last several years I have been investigating the ‘war on cash’: banks and payments companies – who run the underlying digital payments infrastructure – have a huge interest in seeing the demise of the cash system and have actively tried to nudge society away from cash, constantly telling us to ‘prepare’ for an ‘inevitable’ end of cash whilst eroding the cash infrastructure to make it harder to use, and while publishing sob-stories about the need to ‘save’ those who will be ‘left behind’ by this imagined inevitable trajectory that they engineer.

While the banking sector and fintech industry clearly have a commercial agenda in demonising cash, many chain stores do too. Over the years they have tried to automate as much as possible. They invest in self-service checkout systems as a way to automate away their staff, and digital payments is how you automate the money section of a transaction. Big tech firms like Amazon have made no secret out of how they hate non-automated offline payment – they tried to stop pro-cash laws in US cities that would require shops to accept cash – but big supermarkets also prefer to deal with banking giants than to handle physical cash.

Thus, when big chain stores suddenly start asking people to turn away from cash because of ‘safety’ reasons, we should be suspicious of whether they are – in fact – pushing the broader war on cash that has already been occurring for a long time. Every announcement that says ‘please use cards or contactless’ is them saying ‘please step into the arms of the banking sector’. They are thus acting as huge funnels pushing people into deeper dependence on an unstable and often predatory banking system, using a marginal unproven risk as their justification, and whilst neglecting to mention all the risks that come with destroying the cash system.

Overkilling cash

Consider this metaphor. When walking down a city street it is possible that a branch can fall off a beautiful oak tree and kill you, but imagine if – in response to such a death – the city authorities ordered all trees to be cut down. It may be true that they have dealt with the marginal risk of trees killing people in future, but only at the expense of severely harming the overall mental health of millions of city inhabitants (as well as destroying a source of pollution absorption).

There’s a very similar thing happening right now with this cash system. Fine, cash might pose a small risk of carrying infection, along with many other things (like the cooking oil I pick up off the shelf), but the risks that come with destroying the cash system are as high, if not much higher.

The anti-cash brigade don’t mention all the dangerous forms of authoritarian surveillance that accompany the end of cash. They don’t mention the extreme exclusion risks, or the fact that the financial system becomes far less resilient to disasters and crises if the cash system is undermined. They do not mention that pushing people away from cash increases the concentration of power in the banking sector, which but 10 years ago was being vilified as a major source of economic crises (which causes destitution).

It is not ‘responsible’ to promote the end of cash, and it is not responsible to promote digital payment as if it came with no risks itself (the Wirecard scandal should alert us to the fact that these digital payments companies are no angels). It is outrageous that the banking sector is being promoted as something that will save us from coronavirus, and it’s even more outrageous that the big retailers are pushing the banks’ monetary competitor – cash – ever closer to the point of demise on the basis of fake news.

The Shock doctrine of Automation

The only parties that unambiguously gain from the demise of cash are the banking sector and payments companies like Visa and Mastercard. This is why we must draw on Naomi Klein’s concept of the ‘shock doctrine’ and ‘disaster capitalism’ to explain this: when we are in situations of crises we are open to being pushed into increased dependence on powerful actors who will use the heightened social anxiety to present themselves as saviours and push forward new policies and products that will extend and entrench their dominance. Think about that next time a supermarket tells you to not use cash. They present themselves as being concerned for us, but it’s extremely irresponsible for them to ask us to become increasingly dependent on a banking sector that hasn’t ever shown us that has our best interests at heart. Using cash in this scenario is an act of defiance.

Be the first to comment