The problem lurking at the heart of the UK Government’s emerging data strategy and what it tells us about the wider future of data usage

David Beer is Professor for Sociology at the University of York.

Many of the current visions of a technological new dawn share a common property, they are underpinned by an unshakable faith in data. The UK Government’s Data: A New Direction, published on the 10th of September, is steeped in this type of expectation. All our problems will be solved, we might presume, if we can just find the right way to bring out the inherent value of all of this data. A strong sense of inevitability permeates through this turn toward data and the type of hyper-analytic world that it is thought to bring about. Not only do these visions share that unshakable faith in data, they also share a deep-rooted problem.

The projected value of data is perhaps most directly articulated in the government’s statement of their ‘10 Tech Priorities’. The reader need only look as far as number 2 on the list to find it: ‘Unlocking the power of data’. Echoing a familiar cliche, it adds that ‘Data is the driving force of modern economies’. We could easily dismiss these types of hackneyed phrases as yet more government-speak, yet it is this imagining of the power of data that opens the door to expand data processes even further into our lives. The way that data ingratiate themselves into the governmentalities of the day will have tangible consequences for people. These impacts will be felt as a direct result of the way data are used to govern, they will also be a result of how States seek to position themselves within data economies and within a wider data geopolitics.

It is, the top tech priorities continue, ‘by removing barriers to responsible data sharing and use, we aim to become the world’s number one data destination’. In this phrasing the word ‘responsible’ is levied to assuage privacy fears, whilst at the same time barriers are being dismantled to enable the UK to become a ‘data destination’. It is hard to tell if this means that the UK will be importing data for storage or, as is much more likely, opening up the data gathered in the UK for the purposes of value generation (which usually means analysis and targeting). It’s not clear from these stated aims, but this would raise questions over whether the UK might become something close to a data laboratory. As the political economist William Davies once put it, we are ‘living in the lab’.

Data: A New Direction, which is intended as a consultation on the wider data strategy, includes an overwhelming 146 page document with 410 individual items that appear alongside boxed case studies and targeted questions. It’s an almost impossible read, with a vast unanchored terminology and a dizzying range of topics mixed together. The unwieldy content itself alludes to the sheer complexity of the issues being faced and the range of interlaced matters that are implicated by the presence of data. It also hints at the impossibility of spinning all of these plates at once. This vast outline of the issues acts as a follow up to the earlier National Data Strategy, which was published at the end of 2020 and which sought to map-out a broad approach. Taken together, these form part of an evolving strategy and provide glimpses into the government’s emerging approach to data.

The aim of ‘reducing barriers’, as the recent report puts it, is perhaps indicative of how the value of data is being imagined and points at the direction that data regulations, strategies and regimes might be heading. The removal of the barriers that limit innovation and restrict the value of data is a recurring theme. It is here, in this opening of barriers, that we can find the germs of what I will describe as the data problem. The data problem refers to the incompatibility of the pursuit of value through the opening-up of data on one side with the values of those whose data is being opened-up on the other. This data problem is not solely occurring within one nation’s data strategy but will be present in virtually all contexts in which data-led social ordering is pursued.

As we witness the ongoing response to the pandemic, we are likely to find that data are not just part of the way the pandemic is handled and understood but that the potential value of data is also placed centrally within visions of rebuilding, economic recovery and redevelopment. This will accelerate the existing regimes of data accumulation whilst also exacerbating the data problem. These were already pressing times for data policy and the current circumstances mean that these pressures have been heightened, especially as the push toward mediated living – with massive increases in social media activity, video meetings, messaging platforms and online gaming – has only increased the data that are accumulating.

In response, a focus on transformation and efficiency frames the approach that is emerging in the UK. The foreword to the National Data Strategy brings out this faith in data and the changes those data might bring about. The strategy’s development, it claims:

‘means asking fundamental questions about what data should and should not be made available across the UK. It means maintaining a regulatory regime that is not overly burdensome for smaller businesses and that supports responsible innovation. It means driving a radical transformation of how the government understands and unlocks the value of its own data to improve a range of public services and inform decisions at scale, through a whole-government approach driven from the centre. It means taking the risks of increased data use seriously. And it means positioning the UK as a global champion of data use, and encouraging the international flow of information across borders.’

The availability of data is the focal point here – which is posed in terms of questions about which data are sharable and which are not (we might wonder who will decide). Immediately we are taken into a balancing act in which we are expected to decide between privacy and value2. It is implicitly suggested that holding back on data access is to restrict value and to limit the new efficiencies. Within this the UK is also positioned at the forefront of the flow of data across international borders. The UK then is not just seeking to be data savvy, it is is also wanting to become, it would seem, a hub for international data exchanges. We can only begin to speculate on such a role, the type of data being referred to and the nature of the exchanges remain too vague to be certain of what this will mean.

There are some further hints at this direction in the documents even if these are yet to fully solidify. Mostly the emphasis falls back onto the inevitability of the type of future that will be coming anyway, however much we might want to resist, and which will bring with it winners and losers. Anyone who is too slow to react will be out of time. In response to this fear of being left out, the focus tends to be upon the nature of the barriers that stand in the way of the promises of data. The National Data Strategy carries a focus on the boundaries preventing perceived success within the oncoming data future:

‘Data is a non-depletable resource in theory, but its use is limited by barriers to its access – such as when data is hoarded, when access rights are unclear or when organisations do not make good use of the data they already have. These barriers undermine the performance of public services and our economy, risking poorer outcomes for citizens. We will ensure that data can be leveraged to deliver new and innovative services, promote stronger competition, and better prices and choice for consumers and small businesses. We will drive an approach to data that holds that all can benefit when data is used responsibly, and that withholding data can negatively impact society.’

The image is of a wealth of untapped value that only requires an acceptance of the easing of restrictions along with the honing of the skills required to make the most of the newly accessible data. The barriers to access need to be lowered whilst also being much clearer, the result, it is suggested, will be an unlocking of value. The implication is that data openness is of universal benefit whereas maintaining barriers that are too high will have dire social consequences. Such barriers stand in the way of that brighter data fuelled future.

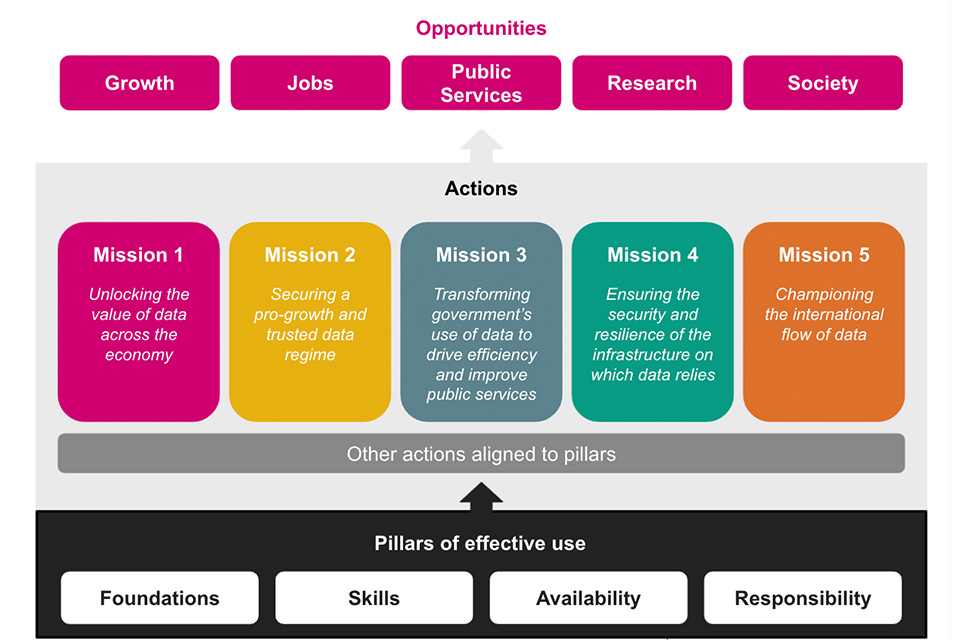

In line with this sense of an inevitable future of data ordering, The National Data Strategy focuses upon, as it puts it, ‘realising the data opportunity’. Realising this opportunity, we are told, requires ‘four highly interconnected pillars that describe the basis for better data use’ (these are also captured at the foot of the above diagram, which is taken from The National Data Strategy document).

The first pillar, ‘Data foundations’, is concerned with improving the quality of data. It is often the case that the promises attached to data are based upon it being cleaner, more accurate and more directly linked to purposes. It is not uncommon for data to be gathered without any sense of what it might be used for and with it needing to be ‘wrangled’ to suit retrofitted objectives. This type of preoccupation with data quality is one that is often repeated in the analytics sector. The second pillar, ‘data skills’, is to do with building-up the skills to gather, clean-up and analyse the data. Yet it is in the third and fourth pillars where we find the data problem most directly embodied within the government’s strategy. The third pillar is labelled ‘data availability’ and the fourth ‘responsible data’. It is here that the tensions will mount. Some will suggest that these two things can be easily aligned, but they cannot. They are unlikely to ever find a neat alignment. In most cases, maximising the value of data is based on making data sources available to those who have the capital to pay for them or who have the capacity to use that data to generate revenue through its use. This is always likely to put availability in tension with responsibility.

Similarly, the variation in understandings about what constitutes responsible data usage will mean that there will always be a significant proportion of people who are not happy with data availability. The only potential way to solve such an impasse is to have highly limited data availability, but this will be interpreted as representing a high barrier that is shutting-down the possibilities for innovation, efficiency, entrepreneurship and, ultimately, the production of value. The point at which no data is made available is likely to be the only point on the graph at which an acceptance with the level of responsibility being exercised will be considered universally acceptable. The forces of capitalism combined with the government’s stated eagerness to tap into the value of data – in their words, ‘Mission one: Unlocking the value of data across the economy’ – means that this will never happen and so these two pillars of the strategy will clash.

The second ‘mission’ stated in the National Data Strategy is to secure a ‘pro-growth and trusted data regime’. This mission adds more fuel to the data problem. Responsibility and trust are only defined in relation to growth and value, and not outside of such concepts. Seeking growth through data will push at the limits of what is considered to be responsible data use. The talk of trust is one thing, but this is not going to be about trust in the sense that we might imagine. Trust in the context of a data future is more often about trust in the quality and reliability of the data. This is clear in the talk of trust being placed directly alongside talk of growth. The focus is upon securing trust from within the logic of value and economic expansion. These two things – trust and growth – are placed in contrast in the very stating of this second mission. The later discussions of ensuring ‘the security and resilience of the infrastructure on which date relies’, the fourth of these missions, is as much about securing an asset and making data usable as it is protecting data rights outside of such concerns. We might wonder if it is the fifth mission, ‘Championing the international flow of data’, that gives an indication of the intention to move toward a particular position within a new type of data market.

Following many of the ideas set out in The National Data Strategy, Data: A New Direction arrives with a reassuring tone, opening with the claim that ‘the government wants to secure an even better data protection regime that fully supports a world-leading digital economy across the UK’. This would suggest a commitment to privacy and careful regulation, yet this will depend on what is meant by ‘secure’ and what is imagined to be an appropriate ‘data protection regime’. Perspectives on these things will vary widely and will be far from compatible. The government’s notion of these things is founded on data being a ‘strategic asset’, indicating that the approach toward data protection will be one in which data are seen to hold particular forms of value. Such a perspective will implicate how security and protection are conceived and implemented. Elsewhere they turn to notions of the ‘responsible use of data’, again though this is couched in how more might be generated from escaping the restrictions of existing regimes, rules and guidance. These existing rules are depicted as having ‘shortcomings’ that restrict agility, especially where the rules are, as they put it, ‘either too vague or overly prescriptive’. We are then seeing an attempt to present data as enabling rapid and quick movements, and that the value of data is based in its ability to facilitate quick decisions. Speed is of the essence it would seem.

In broader terms, the data problem concerns the way that the value produced by data requires privacy to be devalued. Values are in tension with the expected value of data. The expectation is that the greater the relaxation of privacy controls the greater value data will yield. New questions are then created concerning the extent to which the state is prepared to enable access to data in order for its value to be tapped. The temptation is going to be to ride with the forces of capitalism and to open-up data whenever and wherever possible. The problem of data is that such a balance can never be struck. In short, there will never be consensus on where such a line might be drawn – or even what mechanisms might be used to draw such a line. The data problem will persist and will rear up in certain moments when the imbalance between value and values becomes clear.

The data problem is unlikely to disappear of its own accord. It is rather a focal point for conflict and tension that will ensue as long as data are a focal point for the way the social world is ordered and organised. We will not witness a complete resolution of the data problem, at least not unless the routine use of data reaches a point of normalisation in which no questions are really asked. The presence of the data problem is a sign that we are still reflecting on where we wish the line to be drawn and that we are still prepared to assert values over the value of data.

Be the first to comment