How did Thatcherite economic policy become militantly defended orthodoxy on large parts of the left?

David Jamieson is editor of Conter, a Scottish anti-capitalist website.

Cross-posted from Conter

At the Scottish Government backed pro-European Union rally on Saturday (2 September), Humza Yousaf portrayed the EU as a kind of 18-30 package holiday club which would allow Scotland’s young people to “work and study and travel abroad”.

In the days before, Scottish Green co-convenor, Lorna Slater, was much more candid: “Freedom of movement and trade in the EU were among the greatest political achievements for generations”, she wrote.

The Single Market being praised here was a project of Margaret Thatcher, and remains a model of the revolution she and cohorts launched in the 1980s: radical economic liberalisation, empowering capital over workers and breeding extreme inequality. Usually, advocates of Scottish EU membership elide the nature of the bloc – preferring like Yousaf to describe it as a portal for convenient travel or a marker of ‘outward looking’ cosmopolitanism and middle class respectability.

The naked celebration of free trade in recent days marks a turn to the right in rhetoric, and for the independence movement. But it also gives us an opportunity to address what advocates of EU membership usually avoid: a reckoning with what the EU really is.

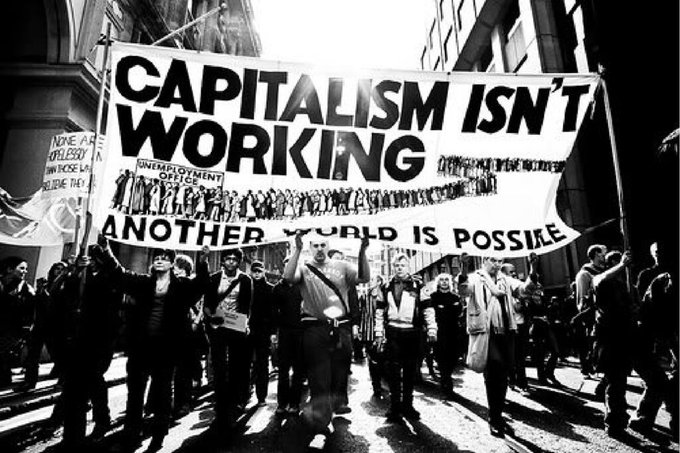

Against Globalism

The arguments outlined in what follows were once the common property of the international left. At the turn of the century, they proliferated in response to the globalisation of free trade regimes and helped restore criticism of global capitalism and elite governance after a decade of post-Cold War triumphalism.A US-led process of trade liberalisation was drawing billons of workers into new conditions of exploitation for a global marketplace. This process knocked-down national industrial policies, welfare regimes and sovereign controls. Huge corporations emerged with significant social and political power, and inequality soared. Transnational institutions were built to manage this global economy over the heads of populations – partly displacing nationally based democratic traditions and institutions like parliaments and political parties. These included the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Trade Organisation (WTO) the World Bank, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the European Union (EU).

In all, this was a major, co-ordinated assault on the global working class. Proponents had a simple message: the rise of the globalised capitalist market was unstoppable, and there was now no alternative, socialism having collapsed in the 20th century. It was therefore vital that the anti-globalisation movement emerged to demand the protection of workers’ rights and living conditions, the environment and democracy. Though this movement bore the scars of defeat and disorganisation, and though its ideas were sometimes confused or primitive, it nonetheless restored the banished criticism of capitalism for the new century.

Contradictions

Contra the prophets of global capitalist triumph, the promised new utopia failed to materialise. The development of global free trade saw new contradictions rend the world system. Far from ‘trade optimisation’ spreading prosperity, liberalised trade caused an explosion of poverty and social dislocation. Inequalities between developed and poorer economies became more pronounced. With the growth of free trade agreements, developing economies were flooded with subsidised goods, and preyed upon by corporations.

Often, the consequence was mass migration from poorer to wealthier economies, and from peripheries to cities. Slum dwelling exploded around the world, and economic growth slowed as national developmentalism gave way to extended global supply chains and fractured, extractive economies. Today, the relative success stories are those countries like China which maintained at least some degree of state direction. Erstwhile rapidly developing forces like Brazil are now succumbing to de-industrialisation. Countries closer the bottom of the pile were hammered.

NAFTA influence in Mexico is an infamous case study. The country’s agricultural system was so badly damaged by the importation of subsidised US goods that it went from food self-sufficiency to dependence on imports. Traditional state guarantees of land to indigenous communities were also scrapped. But these Mexican negatives were not simply balanced by US boons. US manufacturing workers suffered mass unemployment as factory capacity headed south in search of cheaper production. To escape decline, poverty and unemployment, many Mexicans sought refuge over the US border (large numbers dying in the attempt). The same politicians who had signed the free trade agreements, whipped-up anger and paranoia at these ‘illegals’. In addition to the harsh economic consequences for workers in the developed and less-developed sectors of the world system, free trade regimes also saw the curtailment of national democracy and popular sovereignty, and the transfer of power to transnational institutions. A new mode of capitalist rule was being established. It was not ‘post-statehood’: states and elites integrated with the new arrangements, and the US was the undisputed master of the world system. But this did mean a shift in the locus of power and decision making away from populations, and the democratic conquests they had made in the 20th century.

The EU Single Market

What has all this to do with the EU? It is precisely a creature of these historical developments, and in many ways exemplifies the era of globalised neoliberalism and transnational governance.

The EU’s ‘4 Freedoms’ – of capital, goods, services, and movement – launched with the Single Market in 1993, represents the highest achievements of the globalisation era. It seeks to harmonise conditions across the economic bloc and is inspired by hardline neoliberal orthodoxy (as mentioned, Margaret Thatcher was a key instigator of this development along with Jacques Delors in the 1980s).

In its market-building function, the EU bears the same characteristics as other liberal trade associations. It has tended to strengthen the ‘centre’ of the bloc (above all Germany but also northern Europe) at the expense of a ‘periphery’ (principally in the south and east). The periphery provides extended lines of production into the centre, through which value is added. The periphery has also tended to send its labour (via ‘free movement’) to the centre, providing for the needs of western European economies and generating a demographic crisis in parts of the east and south. The conveyor belt moves goods and lines of credit in the opposite direction, burdening the periphery with debt. It would be these imbalances which would erupt into the open with the sovereign debt crisis after 2008.

The swelling inequalities, within and between countries, were presided over by a host of post-democratic institutions. Key among them was the Council of Ministers – leaders representing the elites and business interests of member-states, over the heads of mass national populations, who lost say over vast areas of policy.

The EU in the world

Slater told crowds at the rally that in the EU, we would become “the Scotland of Kenmure street” – referring to protests against the eviction of two men of Indian origin who had lived in Glasgow for many years. This is an asinine claim that betrays deep ignorance about the relationship between the EU and migration flows.

First of all, ‘freedom of movement’ applies only to those living in EU member states and 4 small associate states. It is a system that discriminates against non-Europeans (it would therefore discriminate against the two men in Kenmure Street). The EU not only displaces European populations – it is also a significant factor in the displacement from the ‘global south’ to Europe. Through a combination of economic, military (the EU works in tandem with the NATO military alliance and other facets of western military power) and diplomatic means, the EU dislodges populations from Latin America, Africa and the Middle East.

EU policies abroad mirror those inside Europe. Trade in Africa exploits relative under-development in African industries through Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs). The EU interlocks with other free trade blocs, like Mercosur in South America, where new agreements threaten to further intensify poverty and social inequality.

The European Neighbourhood Policy sees EU elites support – and benefit from relations with – authoritarian governments in North Africa and the Middle East.

Through innumerable channels, then, the EU contributes to the disorder of the world system, to global poverty and authoritarian governance. The population displacement resulting from this drives million to seek refuge in Europe, which rebuffs these incomers with murderous ‘Fortress Europe’ border policies. In recent years, tens of thousands have died in the Mediterranean trying to enter the EU.

Thinking Beyond Global Thatcherism

These criticisms of global capitalism could not be more elementary for the left of some two decades ago. The fact the leading left politicians of today are so ignorant of, or hostile to, these arguments tells a story of defeat and degeneration.

The setbacks faced by the working class and the socialist idea in the late 20th century certainly paved the way for a domesticated left that grudgingly accepted free trade and transnationalism. But this has now warped into enthusiastic, even fanatical support. Slater’s words, and the re-orientation of the independence movement towards capital, also come at a time of change for global politics – with free trade now widely questioned because of its social, political and environmental impacts, and because US hegemony is facing new challenge.

Scots should seek to be part of that challenge, rather than join those speaking at Saturday’s rally in a defence of unaccountable power and immense wealth.

Be the first to comment