When the goal of public health is not the well-being of citizens, but the profits of corporations.

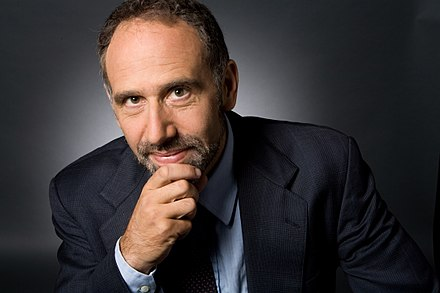

Dean Baker is a Senior Economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR)

Cross-posted from Dean’s Beat the Press Blog

Washington Post columnist Megan McArdle was anxious to tell readers that drug development in the pandemic has been a great success story. After all, look at all the treatments we have, and now it appears that Pfizer/BioNtech have developed a highly effective vaccine. What could be better than that?

Well, first we need a bit of perspective. Yes, we place an enormous value on our health and our lives, so getting effective treatments and vaccines quickly are extremely important. But we do also care about what we pay to get there.

To take my favourite analogy, the firefighter who goes into a burning building to rescue a couple of children can be said to deserve many millions of dollars. After all, we put a huge value on human life. While firefighters are reasonably well-paid, most of their pay checks don’t cross $100,000. Should we pay all of our firefighters $1 million a year? Perhaps in some sense that would be fair, but the reality is that we can get people to do the work for far less.

And, if we want to talk about payments that are commensurate with the value they provide to society, how much did the anti-smoking activists of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s get paid? My guess is that most of the people (I’m sure mostly women) who crusaded to restrict smoking, originally in places like airplanes and restaurants and later public places more generally, got compensated little or nothing for their work. But how many hundreds of thousands (or millions) of lives were saved and heart attacks and strokes prevented as a result of their work. Surely that would be worth many trillions of dollars if we sought to put a price tag on it.

Telling us that the drug companies should get big bucks because their drugs save lives is beside the point. We want to know if the way we finance drug research is the best way, not just that it can lead to successful drugs and vaccines.

And the evidence certainly does not support the view that it is the best way. Let’s start with the best story, the Pfizer/BioNtech vaccine. It will certainly be great news if the initial reports of a 90 percent effectiveness rate hold up when the full results are submitted to the FDA. But how much are we paying for this vaccine?

The U.S. has an advance purchase agreement for 100 million doses (that’s 50 million people since we need two shots) at a cost of $19.95 each. According to some analysts, the vaccine can be profitably manufactured and distributed for roughly $2 a shot. That means we are handing Pfizer/BioNtech $1.7 billion extra to cover its research costs and risks because our government gave it a patent monopoly. (Patent monopolies are not the free market folks, even if right-wingers like them.) That’s a pretty good deal since it’s unlikely their research costs were even one-fourth this amount. And, the U.S. purchase is only about one-fifth of the companies’ expected 2021 output.

It’s also important to note that the Pfizer vaccine, as well as most of the others being worked on now, are heavily dependent on research conducted by NIH. Pfizer also can’t tell the usual story about the many years or decades of research that they claim it takes for them to develop a marketable product. In this case, we don’t need to debate the issue, we know it took them less than nine months.

But rather than arguing whether we are getting a good deal going this patent monopoly route, let’s ask about the alternatives. There was a huge amount of international cooperation early in the pandemic, as scientists freely shared their findings, allowing for enormous progress in understanding the coronavirus.

Suppose this cooperation had continued into the development of vaccines and treatments. This would mean that all research would be fully open and shared across countries. Scientists do need to be paid for their work, but we can do that without patent monopolies. We paid Moderna roughly $1 billion upfront to develop a vaccine. Of course, in the spirit of welfare for drug companies, we are also giving them a patent monopoly on their vaccine.

We could have gone the Moderna route more generally, paying companies to do research in specific areas, but requiring that all results be posted on the web as soon as practical and that patents are in the public domain. That means that any vaccines or treatments can be produced as generics from the day they are approved.

To prevent free-riding we would want some international agreement on cost-sharing with other countries, requiring them to make comparable commitments for research spending given their size and wealth. That would be the sort of thing a competent government could negotiate, even if it might have been inconceivable for Donald Trump.

Would this route have gotten us a vaccine sooner? It is very possible that it would. Several Chinese companies have developed vaccines that are already far along in Phase 3 testing. One of these companies is planning to ship 46 million doses to Brazil later this month. Hundreds of thousands of people in China have already received one of the vaccines based on an Emergency Use Authorization. That may not be a good public health practice, but it does mean that we can be reasonably well-assured that the vaccines do not have serious short-term side effects.

Without more access to the data, we can’t know whether China’s vaccines would meet our standards and qualify for FDA approval. However, if we had gone the collaborative route we would have this data. And if the tests done by China’s companies were not adequate, we could do additional tests ourselves.

It is also important to note that China’s leading vaccine candidates are old-fashioned dead virus vaccines. As a result, they don’t require the super cold storage of the Pfizer/BioNtech vaccine. In a world where the U.S. is now seeing more than 140,000 new cases a day and 1,400 deaths, getting a vaccine distributed even a few weeks earlier can mean millions of fewer infections and tens of thousands of fewer deaths.

We can’t know that this collaborative route would have produced an effective vaccine more quickly, but we certainly can’t rule out that possibility. In other words, McArdle’s celebration of the success of the U.S. drug development system is based on nothing.

But we can also look at treatments. Here we have an even murkier picture. While the monoclonal antibodies being developed by Eli Lilly and Regeneron show considerable promise, the first drug pushed as an effective treatment was Gilead’s Remdesivir. Gilead was charging over $2,000 for a course of treatment with this drug. High quality Indian generic manufacturers were charging less than one-tenth of this price. Remdesivir was also developed with considerable government support.

But even more important than the high price is the possibility that Remdesivir may not actually be an effective treatment. While the initial trial results were promising, the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the drug is ineffective in treating the coronavirus. Gilead disputes the WHO’s assessment and it’s possible the company is correct, but there is a simple point here; patent monopolies give drug companies a large incentive to lie.

The Indian generic manufacturers make a profit when they sell the drug for $250 for a course of treatment. But when Gilead sells it for more than $2000, it effectively has a mark-up of 1000 percent. These sorts of mark-ups give drug companies an enormous incentive to exaggerate the effectiveness of their drugs and conceal evidence of harmful side effects.

If this sort of lying is hard to imagine, let me tell you about the opioid crisis. The major opioid manufacturers have paid out billions of dollars in settlements over allegations that they deliberately concealed evidence on the addictiveness of the new generation of opioids. (For some reason, I have literally never seen any mention of the perverse incentives created by patent monopolies in discussions of the opioid crisis.)

Anyhow, I will leave the determination of the true effectiveness of Remdesivir to people more competent in the area, but it is important to note that because of its patent monopoly Gilead has a powerful incentive to not be honest in this debate. If that has led people to be improperly treated for the coronavirus, that is a very serious downside to the way we finance drug research.

In short, it takes a very selective reading of the evidence to pronounce the performance of the pharmaceutical industry in response to the pandemic a great success. We should undoubtedly be happy that we will soon have an effective vaccine and treatments, but that does not in any way establish that we followed the best path to get here.

In the old days, many countries were pursuing import-substitution as a route to development. There were some successes, but in many cases, countries would end up with factories that produced steel, cars, or other products at two or three times the world price. They could then brag that they were producing 10 million tons of steel or 2 million cars a year, but the reality would be that these projects were disastrous failures. Based on the available evidence, we cannot say that we don’t have a failed pharmaceutical industry.

Be the first to comment