What are the social impacts of pollution, climate change and policy responses? What social inequalities exist? And how would benefits and burdens be fairly distributed? The diversity of social aspects and equity issues must be taken into account as much as possible in environmental policy discussions as well as in research work

Dirk Arne Heyen is an expert on social aspects of environmental policy and transformation processes at the Öko-Institut

Cross-posted from the Öko-Institut

People participating in Fridays for Future demonstrations frequently call for “climate justice”, by which they mean more ambitious climate policy and action by the current generation and the countries of the Global North that are primarily responsible for climate change. On other occasions, trade unions call for a ”just transition”, by which they mean political support for employees affected by ecologically driven structural change, for example in the coal and automotive industries.

Welfare organizations, meanwhile, regularly use the term “energy poverty” (or “energy justice”) to warn against the negative impact of rising energy prices on the accessibility and affordability of energy for low-income households. At the same time, use is made of the term “environmental (in)justice” to make clear that it is primarily these households that also suffer from poor environmental conditions, for example living near a main road with poor air quality or lacking green spaces in their vicinity.

Evidently, what actors refer to when talking about social aspects of climate change or what they mean when speaking about “just environmental policy” can vary widely. This is hardly surprising, as environmental and social issues overlap in many ways.

Different social justice dimensions

Casting the above examples in more abstract terms, the following social justice dimensions can be distinguished in the context of climate action and environmental protection:

- the unequal distribution of environmental benefits and burdens,

- the unequal causation of these environmental burdens,

- the unequal distribution of benefits and costs (e.g. jobs, access to products and services) of socio-technical systems such as energy and transportation, and

- cross-cutting and influencing the former dimensions: the unequal distribution of benefits and burdens of environmental policies and transformation processes – with regard to such diverse impact categories as paid employment and care work, household income and expenditure, health and psychosocial effects, or everyday life and leisure.

In addition to these aspects of “distributive justice”, justice discourses often also deal with access to information, opportunities to exert influence and gain legal protection (procedural justice), as well as with the question of social recognition of different population groups (recognitional justice).

Socially, spatially and temporally distributional effects

Impacts like environmental or financial-cost burdens, for example, can be distributed very unequally – in social (socio-structural), spatial and temporal terms. From a socio-structural point of view, one can analyse differences depending on income group, employment, gender, age, or household size, for example. Moreover, certain lifestyle characteristics, such as the main means of transport, or whether one lives in one’s own house or in a rented flat, can lead to differences in how climate policy measures affect people.

With regard to spatial distribution, differences can be analysed, for example, between industrialised and developing countries (e.g. in the causation and consequences of climate change), between coal-mining and other regions (e.g. in the course of the energy transition), between urban and rural areas (e.g. in the case of fuel taxes), or between rich and poor districts (e.g. regarding air pollution).

Finally, in temporal terms, environmental problems or employment and income effects may vary at different points in time: today and in ten years from now, or between different generations, including generations to come.

Thus, there is potentially a wide range of inequalities. But is an unequal distribution always unjust? And what would be a just distribution?

Various principles of a just distribution

Let us assume that we want to divide a cake among three children. What is the best way to proceed? Each child receives one third of the cake? Or each one gets a piece depending on age and size? Or child A should get the biggest piece because he/she helped bake it? Or child B because he/she likes this kind of cake most? Or child C because he/she is the hungriest?

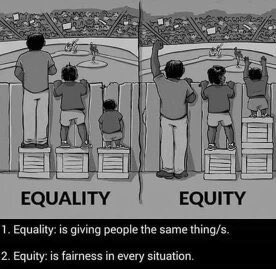

The example shows that there is a whole range of different justice considerations. Broadly speaking, three principles of a just distribution can be distinguished: 1) equality, 2) proportionality, and 3) minimum threshold, i.e. prioritising the fulfilment of basic needs or fundamental rights of all, beyond which inequality is considered legitimate (or another principle is then applied).

However, even equality can be understood differently: should everyone be treated equally by a measure (e.g. get the same per-capita payment from CO2 tax revenue), or should everyone end up having the same or being able to do the same (e.g. be able to consume the same amount of energy)? In the latter case, unequal treatment will often become necessary.

The proportionality principle can also be applied quite differently: Should costs be distributed depending on the share of problem causation, on future benefits, or on resources and capacities? Should historical use rights or past contributions to problems and solutions be taken into account?

It is not the purpose of this paper to advocate for any particular principle or combination of them. Rather, the goal has been to highlight the diversity of social aspects of environmental policy, and especially of possible distributional issues and normative principles of valuation. It is important to take this diversity into account as much as possible in policy discussions as well as in research.

Be the first to comment