Not one of the stablecoins currently in circulation lives up to its name.

Frances Coppola is the author of the Coppola Comment finance and economics blog, which is a regular feature on the Financial Times’ Alphaville blog and has been cited in The Economist, the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Guardian. Coppola is also Associate Editor at the online magazine Pieria and a frequent commentator on financial matters for the BBC

Cross-posted from Frances’s Blog Coppola Comment

Stablecoins aren’t stable. So-called algorithmic stablecoins crash and burn when people behave in ways the algorithm didn’t expect. And reserved stablecoins fall off their pegs – in either direction. A stablecoin that does not stay on its peg is unstable. Not one of the stablecoins currently in circulation lives up to its name.

Don’t believe me? Well, here’s the evidence. Exhibit 1, USDT since the end of April:

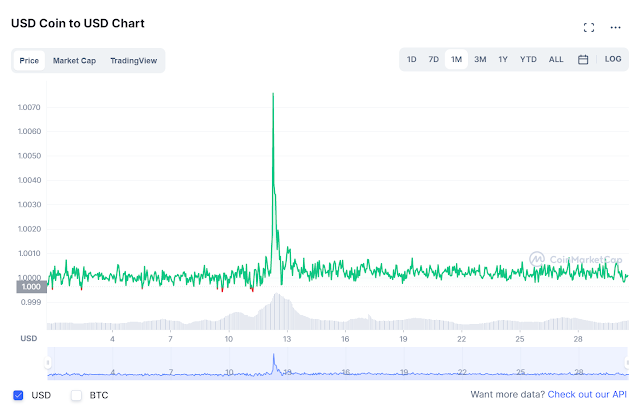

Exhibit 2, USDC over the same time period:

(charts from Coinmarketcap)

So USDC and USDT are equally unstable, just in opposite directions. Why is this?

The reason for the discrepancy appears to be market perception that USDC is “safe”, while USDT is risky. On 12th May, crypto markets melted down as the UST algorithmic stablecoin crashed, triggering a flight to what in the crypto world passes for “safety”.

For genuine crypto diehards, “safety” is BTC, which although highly volatile does seem to generate value over the longer term. But for the thousands of speculators, investors and amateur traders who are dabbling in crypto in the hope of finding some yield in an era of low interest rates, “safety” is fiat currency. Specifically, U.S. dollar-denominated “safe assets”.

Like traditional financial markets, crypto markets use safe assets as media of exchange, collateral, and a safe haven in times of distress. The world’s premier safe assets are USD-denominated assets such as dollar bills, FDIC-insured bank deposits, and U.S. treasury bills. But these aren’t terribly liquid on crypto markets and can be in very short supply. So the crypto world has created its own versions of them that can be produced in potentially unlimited quantities to meet the crypto market’s need for safety and liquidity. USD-pegged stablecoins are crypto versions of USD-denominated safe assets.

But not all stablecoins are perceived as completely safe. There’s very definitely a hierarchy of stablecoins. “Fully reserved” stablecoins such as USDC are premium products, since they are seen as safe stores of value as well as highly liquid media of exchange. Fractionally reserved stablecoins like USDT are convenient as media of exchange but are distrusted as stores of value. And algorithmic stablecoins mostly seem to be used as a risky lending product generating very high returns.

Such a difference in risk perception should be reflected in price differentials. And to some extent, it is. In DeFi borrowing, there’s typically a larger haircut on USDT collateral than there is on USDC. But because of the USD par peg, the coins themselves don’t have a price difference – until there is a market panic. Then the pegs fail, the safe asset (USDC) trades at a premium and the risky asset (USDT) trades at a discount. When both de-pegged on 12th May, we briefly saw their real prices until the automated wash trading that both issuers employ brought them back close to their pegs. But despite the bots’ best efforts, USDC is still trading at a slight premium and USDT at a small discount, reflecting continuing market uncertainty.

The crypto market has convinced itself that USDC is as good as a U.S. dollar. The fact that USDC tends to trade above its peg merely reflects the fact that USDC is more liquid than USD on crypto markets and thus has greater utility. To all intents and purposes, a USDC token is a dollar.

But it’s not. USDC is the safest asset available on crypto markets, but it’s not a safe asset. There is no such thing as a safe stablecoin.

A new research paper by Ben Charoenwong, Robert M. Kirby and Jonathan Reiter says that the only type of stablecoin that can guarantee to hold its USD peg under all conditions – and therefore be a credible safe asset – is one that is fully backed by hard dollars in the manner of a currency board. Algorithmic stablecoins like UST cannot be guaranteed to hold their pegs under all conditions. For fractionally-reserved stablecoins, overcollateralization (holding a portfolio mix of safe and risky assets whose total market value exceeds that of the stablecoins in issuance) offers some protection, but bleeds value over time. In some state of the world, therefore, even overcollateralized stablecoins can lose their reserve backing and fall off their pegs (or be forced off them).

It’s worth examining how the authors draw this conclusion. Firstly, they use a mathematical theorem (Rice’s theorem) to show that the smart contracts underpinning stablecoins cannot possibly compute for all present and future states of the world, and that failures are therefore inevitable.

This might seem obvious, but unfortuately many people in the crypto world appear oblivious to the limitations of code – or have too much invested in it, both personally and financially, to believe that it can fail or that any failures would personally affect them.

The authors’ use of Rice’s theorem is unfortunately open to challenge. They arbitrarily set a limit on the number of blocks within which a stablecoin must regain its peg, on the reasonable grounds that if there is no limit then everything is a stablecoin. But imposing such an arbitrary limit renders Rice’s theorem inapplicable, since it can’t be assumed that every Turing machine will have the same limit.

Nonetheless, their general point still stands: even if Turing completeness does not apply, a program still cannot compute for all states of the world, since code is written by humans and no human has perfect foresight. Code can be proved to do what it is designed to do, but it can’t be proved either to do or not do what no-one ever thought it should do. When I was a programmer, we used to call a program that failed because it encountered an unforeseen situation an “OSINTOT” – “Oh Sh*t I Never Thought Of That”. The crypto world is full of OSINTOTs.

The authors then consider what they call “hybrid backing”, where a USD-pegged stablecoin is backed by a mix of risky assets whose market value exceeds the total value of stablecoins issued (overcollateralization). If the market value falls to par, then the assets are automatically exchanged for USD in what the authors call a “stop-loss” strategy. Executing the stop-loss temporarily creates a currency board, though the USD can be exchanged for risky assets again once the market recovers. However, in a repeated sequence of stop-losses, the portfolio’s value is progressively eroded to the point where the USD realised on executing a stop-loss becomes insufficent to back issued stablecoins. When this happens, the par peg fails. Overcollateralization with risky assets therefore cannot guarantee the peg.

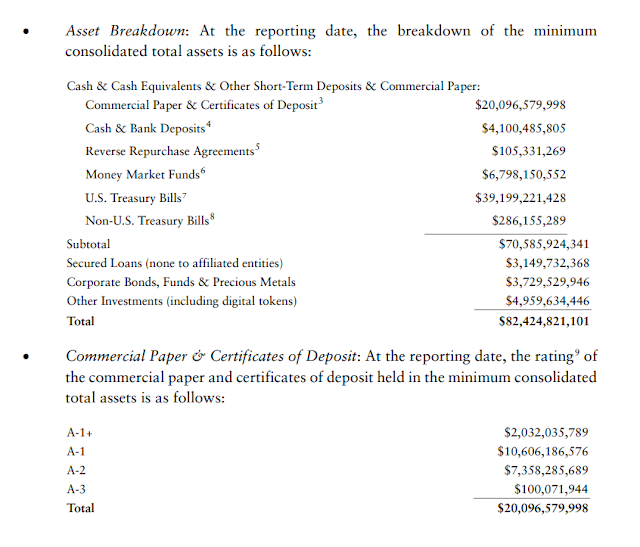

USDT is a stablecoin with “hybrid backing”. The attestation it released in May 2022, which was a snapshot taken on 31st March, revealed the following mix of assets:

The proportion of conventional safe assets, notably U.S. Treasury Bills, is quite a bit higher than in previous attestations. But there is still substantial credit and market risk in this portfolio. It is not by any stretch of the imagination a currency board.

But maintaining 100% liquid USD reserves necessarily means limiting stablecoin issuance. Circle can only issue the number of stablecoins for which it is able to obtain reserves. It is not a bank, so it can’t obtain dollars from the Fed. It must buy or borrow reserves on the open market. This explains why it de-pegged during the May market panic. It could not obtain reserves fast enough to issue the quantity of USDC that investors were demanding, so the price rose sharply.

So we have a paradox. A fully-reserved stablecoin that relies totally on financial markets to obtain the reserves it needs to maintain its peg can’t guarantee to maintain its peg.

How can we resolve this paradox? Well, the obvious solution is for the stablecoin issuer to become a bank. That would give it access to unlimited dollar reserves. But it would need to maintain sufficient high-quality collateral to obtain them – and guess what the prime collateral accepted by central banks is? Why, short-dated government debt, of course, which the stablecoin issuer would have to obtain from markets (unless it became a broker-dealer). If a stablecoin issuer couldn’t obtain sufficient T-bills to maintain 100% reserves in a market panic, how would it obtain sufficient T-bills to borrow those reserves from the Fed? I’m not sure those who argue that stablecoin issuers should become 100% reserve banks have quite thought this through. If a stablecoin issuer with a Fed master account must obtain collateral from markets in order to borrow the reserves it needs to hold its peg, then it cannot guarantee its peg.

So becoming a bank would not resolve the paradox. And this, I’m afraid, is where the self-referential nature of private sector stablecoins fundamentally fails. Even if they maintain 100% hard dollar reserves, USD-pegged stablecoins cannot guarantee their own pegs.* And for that reason, they cannot be safe assets.

In conventional licensed banks, the central bank guarantees the par peg between bank deposits and bank reserves/physical cash, provided that the bank is solvent: if the bank is insolvent, then the peg is often still guaranteed by deposit insurance schemes, though this may only be for relatively small amounts. No doubt some will argue that central banks should similarly guarantee the par peg for 100% reserved stablecoins. But if a stablecoin requires a central bank to guarantee its peg, and insurance to protect its depositors from losses, in what way is it materially different from a bank deposit account?

Furthermore, even without a Fed guarantee for the par peg, maintaining 100% reserves in cash and short-term government obligations renders trustlessness and decentralization impossible. As Charoenwong, Kirby and Reiter observe (my emphasis),

..if we require stability with respect to an off-chain balance – for example USD – then we need to hold that asset in the treasury. If that asset is not natively on-chain then this process must require a trusted off-chain connection.

So we need T-bills and cash on the blockchain, eh? Hello, CBDCs and tokenised government debt.

And this is indeed where the authors end up:

Any truly reliable stablecoin will look like a wrapper around central bank currency or government debt instruments regardless of whether such assets are tokenized on a blockchain, held book-entry in a database or recorded using any other technology.

So a 100% reserved USD-pegged stablecoin is in reality a wrapped Fed dollar. It is not difficult to foresee that if the Fed produced a CBDC, it would quickly be locked up as reserves by private sector stablecoin issuers, especially if it paid interest. And so would tokenised T-bills.

Support us and become part of a medium that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment