Although macroeconomic populism failed on Truss’s watch, she was neither its source nor its principal architect – that was Boris Johnson. And the source was George Osborne. [This prescient article was written before Truss’s resignation]

Frances Coppola is the author of the Coppola Comment finance and economics blog, which is a regular feature on the Financial Times’ Alphaville blog and has been cited in The Economist, the Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Guardian. Coppola is also Associate Editor at the online magazine Pieria and a frequent commentator on financial matters for the BBC.

Cross-posted from Frances’s blog Coppola Comment

George Osborne – Photo credit: Gareth Milner

At the Battle of Ideas on October 15th, a panel on “populism” spent an hour and a half discussing everything except economics. Sherelle Jacobs of the Telegraph called for the Tory party to replace what she called a “twisted morality of sacrifice and dependency” with the “Judaeo-Christian” values of thrift and personal responsibility. And when a brave audience member asked “shouldn’t we be discussing economics?” Tom Slater of Spiked brushed him off and carried on talking about cultural issues. Economics be damned, populism is all about morality and culture.

But important though morality and culture are, it is economics that really matters. Rudiger Dornbusch’s work on macroeconomic populism shows that populism eventually fails because the economics don’t work. And when it does, the people who suffer most are those the populists intended to help.

In this study (pdf), Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards define macroeconomic populism thus:

Macroeconomic populism is an approach to economics that emphasizes growth and income distribution and deemphasizes the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies.

Liz Truss’s disastrous budget meets this definition. It was explicitly intended to stimulate growth, and she and Kwarteng ignored the risks of inflation and deficit finance, wrongly assuming that external investors and domestic voters would approve of the plans. Furthermore, the package as a whole was aggressively redistributive, cutting taxes predominately for the rich and supporting household incomes right across the income distribution.

But although macroeconomic populism failed on Truss’s watch, she was neither its source nor its principal architect. The principal architect was Boris Johnson. And the source was George Osborne.

Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards locate the source of populism in austerity. “The populist paradigm is typically a reaction against a monetarist experience,” they say. And they go on to explain how economic stagnation results from austerity:

Initial Conditions. The country has experienced slow growth, stagnation or outright depression as a result of previous stabilization attempts. The experience, typically under an IMF program, has reduced growth and living standards. Serious economic inequality provides economic and political appeal for a radically different economic program. The receding stabilization will have improved the budget and the external balance sufficiently to provide the room for, though perhaps not the wisdom of, a highly expansionary program.

This well describes the UK of the early 2010s. The economy was stagnant, growth was slow and living standards were poor. And although the UK was not subject to an IMF programme, other countries in Europe were. George Osborne and David Cameron leveraged fear of becoming “like Greece” to convince a long-suffering population that austerity now was necessary to ensure growth and prosperity returned in the future.

But by 2015, growth and prosperity had not returned. Rising inequality and poor living standards, particularly outside London and away from big cities, fuelled popular anger. With rebellion against austerity in the air, Osborne engineered something of a housing boom in time for the 2015 election and succeeded in winning an outright majority for the Conservative party. Just over a year later, both Osborne and Cameron were out of office. But the Conservative party wasn’t.

The turn to populism often starts with the election of a left-wing government. But in the case of the U.K., it didn’t. It started with the campaign to leave the EU. Brexit is a populist movement, but not a socialist one. Many of its proponents want free markets and a small state, and while others want a bigger role for the state, they see it as fostering enterprise in left-behind regions. “Take back control”, cried the Leave campaign. “WE WILL!” shouted back the voters in the 2016 referendum. The following day, Cameron resigned. His replacement, Theresa May, sacked Osborne.

May continued to make deficit-reducing spending cuts throughout her premiership. In 2018 she promised to end austerity “when Brexit was done“. But within a year she too was out of office, replaced by Boris Johnson, a leading light of the Brexit movement. In December 2019, the Conservative party won a landslide victory on Johnson’s promises to “get Brexit done” and “level up” the country. And so it came to pass that the same centre-right political party that had inflicted the austerity of the post-crisis years, rejected it.

Johnson told voters that austerity was over, and promised large-scale investment in infrastructure and public services. Suddenly, the government deficit and debt, on which attention had previously been lavished to the point of fetishism, was no longer important. The government had sufficient fiscal room to do whatever it wanted. And when the Covid pandemic hit, all constraints on government spending were removed. The UK had pivoted fully from austerity to Dornbusch’s “no constraints”:

No Constraints: Policy makers explicitly reject the conservative paradigm. Idle capacity is seen as providing the leeway for expansion. Existing reserves and the ability to ration foreign exchange provide room for expansion without the risk of running into external constraints. The risks of deficit finance emphasized in traditional thinking are portrayed as exaggerated or altogether unfounded. Expansion is not inflationary (if there is no devaluation), because spare capacity and decreasing long run costs contain cost pressures and; there is room to squeeze profit margins by price controls.

To be sure, the UK was far from alone in removing all constraints at this time. Governments all over the world were spending without limit, supported by massive QE from their central banks. But Johnson’s agenda was far more than just a pragmatic response to a public health crisis. It was a radical populist programme:

The Policy Prescription. Populist programs emphasize three elements: reactivation, redistribution of income and restructuring of the economy. The common thread here is “reactivation with redistribution”. The recommended policy is a redistribution of income, typically by large real wage increases.

Johnson’s rejection of his predecessors’ austerity was accompanied by an explicit commitment to redistribution and restructuring not only of the UK economy, but of society. The “levelling up” agenda that bought him the votes of the “red wall” aimed to close the wide income and wealth gap between London & the South East and the rest of the UK.

Johnson’s profligacy led to carelessness and corruption, both financial and personal. Eventually, it brought about his downfall. But Truss inherited his mandate, and although her first action on coming into office was to downplay “levelling up” in favour of an equally radical “growing the pie”, her plan for tax-light “enterprise zones” across the country was, at least in theory, strongly redistributive. Her mini-budget was every bit as populist as Johnson’s programme. But not more so. Had he remained in office, Johnson’s populist programme would eventually have unravelled as disastrously as hers – because populist programmes always do.

Dornbusch and Edwards document four phases in the collapse of macroeconomic populism, which I reproduce verbatim below. Their work is on Latin American countries, so not entirely applicable to the UK. But the lessons nonetheless are valuable.

- Phase I: In the first phase, the policy makers are fully vindicated in their diagnosis and prescription: growth of output, real wages and employment are high, and the macroeconomic policies are nothing short of successful. Controls assure that inflation is not a problem, and shortages are alleviated by imports. The run-down of inventories and the availability of imports (financed by reserve decumulation or suspension of external payments) accommodates the demand expansion with little impact on inflation.

- Phase II: The economy runs into bottlenecks, partly as a result of a strong expansion in demand for domestic goods, and partly because of a growing lack of foreign exchange. Whereas inventory decumulation was an essential feature of the first phase, the low levels of inventories and inventory building are now a source of problems. Price realignments and devaluation, exchange control, or protection become necessary. Inflation increases significantly, but wages keep up. The budget deficit worsens tremendously as a result of pervasive subsidies on wage goods and foreign exchange.

- Phase III: Pervasive shortages, extreme acceleration of inflation, and an obvious foreign exchange gap lead to capital flight and demonetization of the economy. The budget deficit deteriorates violently because of a steep decline in tax collection and increasing subsidy costs. The government attempts to stabilize by cutting subsidies and by a real depreciation. Real wages fall massively, and politics become unstable. It becomes clear that the government has lost.

- Phase IV: Orthodox stabilization takes over under a new government. An IMF program will be enacted; and, when everything is said and done, the real wage will have declined massively, to a level significantly lower than when the whole episode began! Moreover, that decline will be very persistent, because the politics and economics of the experience will have depressed investment and promoted capital flight. The extremity of real wage declines is due to a simple fact: capital is mobile across borders, but labor is not.

The extraordinary conditions of the pandemic complicate things somewhat. But looking back, it can be said that the macroeconomic policies of the pandemic were successful, and their enormous expense was not a problem because the central bank was – unusually for the UK – captive at that time. I find it odd that those complaining about the threat of fiscal dominance in the Bank of England’s handling of the gilts meltdown under Truss have failed to notice two whole years of actual fiscal dominance under Johnson. The Bank of England explicitly ensured that Johnson’s government could finance exorbitant expenditure on covid-related schemes. I am not saying that this was a mistake: there was a clear need for coordinated government and central bank action to keep people and businesses alive during successive lockdowns. But we should beware of double standards. Johnson’s extraordinary profligacy was supported by the Bank of England and accepted by markets. Truss’s was not.

So the pandemic period was Phase 1, when the populist paradigm works brilliantly. And thank goodness for it. Attempting to do austerity at that time would have been disastrous.

The cracks started to appear as the economy reopened. Supply chain problems caused shortages and price rises. Inflation started to rise. This was Phase 2.

Political instability and the Ukraine war ushered in Phase 3. Energy prices spiked and inflation shot up. Johnson was ousted by his own MPs, and there was then a protracted leadership campaign, during which the eventual winner, Liz Truss, said some worrying things and made some unwise promises. By the time she took office, gilt yields were already rising and sterling experiencing considerable volatility. But the wheels came off with the “mini-budget” on September 23rd.

Quite why Truss thought she could introduce a wildly profligate budget when inflation was high and rising, interest rates rising and sterling already under pressure is unclear. Perhaps she genuinely thought she would be able to face down financial markets. After all, her government wasn’t socialist, it was a right-wing, true-blue Tory government with an agenda modelled on the successful tax-cutting programmes of Thatcher and Reagan. Surely financial markets would approve?

But financial markets are amoral. They don’t care whether a government favours the rich or the poor. They only care that its economics make sense. Truss’s didn’t. So they punished her in exactly the same way that they would a socialist government pursuing a massive programme of unfunded welfare increases at a time of rising inflation, binding resource constraints and near-full employment. They sold everything denominated in sterling, including sterling itself. Capital fled from the UK.

Dornbusch doesn’t mention the importance of personalities, but in my view part of Truss’s problem is that she isn’t Johnson. She is, if you like, the UK’s equivalent of Nicolas Maduro, the Venezuealan leader who took over from Hugo Chavez but has never commanded his popularity. Truss has neither Johnson’s popular appeal nor his communication skills. Johnson might have been able to blag his way through the return of the bond vigilantes, but Truss, wooden and unempathic, never stood a chance.

Now, the UK is in phase 4. The Conservatives have appointed a new Chancellor who has already taken a hatchet to Truss’s tax-cutting budget and is indicating further cuts to come. And with her entire economic programme now in shreds on the floor, Truss seems unlikely to be able to hold on to office for much longer. It is not at all clear who will replace her, and the prospect of the Conservatives putting in place an unelected technocratic government with no mandate to undertake the fiscal consolidation that is now necessary is profoundly undemocratic. We need a General Election, not a Tory coronation.

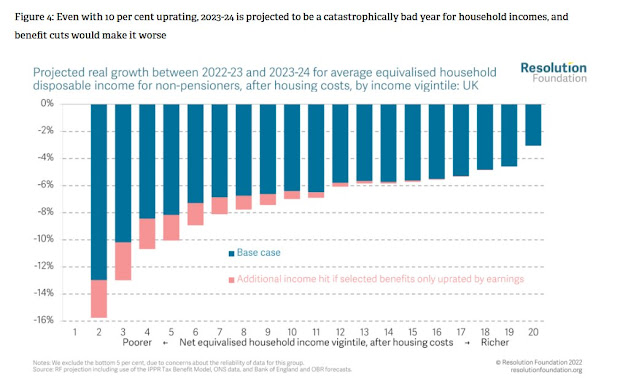

We have come full circle. Austerity is back, bigger than before. And those who will pay are the very people that voted for Johnson and for Brexit because they thought this would make their lives better. Just as Dornbusch and Edwards predicted, there will now be brutal real income falls across the entire income distribution. This chart from the Resolution Foundation is unbelievably stark:

Nor are pensioners likely to escape the income squeeze. The Chancellor has already indicated that he may take his hatchet to the sacred triple lock that ensures their state pensions always rise by as much or more than inflation and average earnings. And the returns on their savings are unlikely to keep up with inflation.

Why do populist programmes always end disastrously for those they aim to help? It’s not because of lack of commitment, or failure to make the case for them. Populist leaders often believe strongly in their programmes. It is the economic substance of the programmes that is the problem. Populist politicians think the rules of economics don’t apply to them. They eventually find out the hard way that they do.

Truss’s attempt at a Barber-style “dash for growth” was short-lived, but its consequences will be long-lasting. The UK now faces persistently raised interest rates, a persistently weaker currency, and persistently higher government borrowing costs as a direct result of her folly.

Sadly, as Dornbusch and Edwards warn, the return of austerity, if not tempered by measures to improve growth and what they call “social progress”, will sow the seeds of the next crisis. And this is where those who see populism as being about morality and culture perhaps have something important to contribute. For it is morality, not economics, that says the social fabric of society is important and must be maintained.

Osborne’s economics-driven austerity shredded social safety nets and rendered essential public services unfit for purpose. It is vital that the new technocratic government does not embark on the same disastrous course. We don’t need a “new morality”, we need to reinforce our traditional British – indeed, dare I say it, Judaeo-Christian – values of fairness, duty, compassion and generosity.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us going.

Be the first to comment