Ben Wray, the Gig Economy Project’s co-ordinator, recently travelled to Berlin to find out about the vibrant grassroots movement of gig workers in the city, organised via worker collectives. Here’s what he found.

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy. If you have information or ideas to share, please contact Ben on GEP@Braveneweurope.com.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in Europe is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Andrew Wainwright Reform Trust.

I walk in to a ground-floor office at the end of a long meeting of riders from at least five different food and grocery delivery platforms. I’m told they try to hold these ‘coalition’ meetings every Sunday. They look tired, and one of them says he’s just about out of energy for the day.

As I wait for the meeting to finish, I have a look around. The room is covered in flip charts filled with schemes for organising and campaign building. There are leaflets on the table about wage theft, one about an upcoming workers council election at Lieferando, and another about labour rights in Germany for non-native speakers. On one wall there’s a ‘re-elect Frank Sobotka’ poster, the fictional trade union leader in the second series of The Wire. It’s clear this place is no bog standard office. It’s a hub of grassroots union organising.

A day in the life

Avik from the Gorillas Workers Council is an ever-present for the four days in which I turn up at the office. He tells me that he sometimes sleeps at the office, he also has keys for flats he can stay at if he wants to, but he doesn’t have a permanent place to stay.

“It’s fine,” he says, as I look at him with a slightly alarmed expression.

Avik is at the centre of a storm at Gorillas, but he always seems to be the most relaxed person in the room. He’s been fired by the company but was re-hired after winning a court case in December. Now Gorillas is appealing that decision. Meanwhile, he hasn’t done a shift at the company since March, and he claims he wasn’t being paid properly before that anyway, and has never been paid a penny for his work at the Workers Council. He seems to take it all in his stride, spending every day organising to get other workers the pay they’re owed.

“I’m from India; this isn’t hard,” he says.

The most dramatic of my four days at the office gives an indication of what this is all about. In the afternoon, a Gorillas manager, supervisor and former HQ staffer are there and speak to a posse of journalists about how badly the company treats its workers. The place has become a magnet not just for worker discontent, but for sacked supervisors and managers too. In the evening, a dozen riders threatened with redundancy turn up and are supported with legal advice by a student lawyer.

READ MORE: Gorillas in Berlin: chronic problems and mounting divisions

“Our group has been in support of the Gorillas Workers Collective with different stuff,” Robin, the student lawyer from ‘Leftist law students organising themselves’, tells me. “We have been around the whole Workers Council election process [in December] and afterwards they reached out to us because there are very many cases that need to be taken care of.”

One of the rider’s says she didn’t think much of the Workers Council until recently, but after seeing her and 18 of her colleagues get a new contract or compensation because of the intervention of the Council, she now understands that “yes, it’s really important”.

Not content with all of that, as the sun begins to set Avik manages to recruit a Lieferando rider who is just cycling by on a delivery. After 15 minutes of talking in what I presume to be Hindi, the customer shouts down from a balcony asking if he can get his order and they can continue the conversation after. The rider apologetically delivers the order, comes back to the office and starts filling out papers with Avik. Job done.

“What we try to focus on here is the worker”

It should go without saying that not everywhere in Europe is there such a dynamic grassroots organising movement, so what explains this phenomenon?

One could point to the Workers Council, which all the rider-organisers agree has become a key part of the strategy for them in every platform, and is of course not something which is available to workers in most countries in Europe. On the otherhand, the success of organising at Gorillas in particular could lead one in the direction of the fact that these workers are employees and congregate at warehouses (‘dark stores’) – maybe that’s the recipe for their success? Max, from the Lieferando Workers Collective, insists none of these explanations get to the heart of the issue.

“There are warehouses at Flink, but there’s nothing happening, so it cannot be about the warehouses,” he says.

“There is no crucial factor to this which is external to workers. We are the key, we are the major factor which makes organising and unionising possible.

“So what we try to focus on here is the worker, and bringing together these workers and sharing knowledge and opportunities with them. We try to emphasise that you need a bunch of workers to do shit.

“There are always objective factors, some are beneficial some are not, but there is no excuse to say ‘we don’t get organised because we don’t have a warehouse’. It’s about the people, and the mindset of the people.

“In February last year, the right set of people came together at Gorillas, and this is the outcome.”

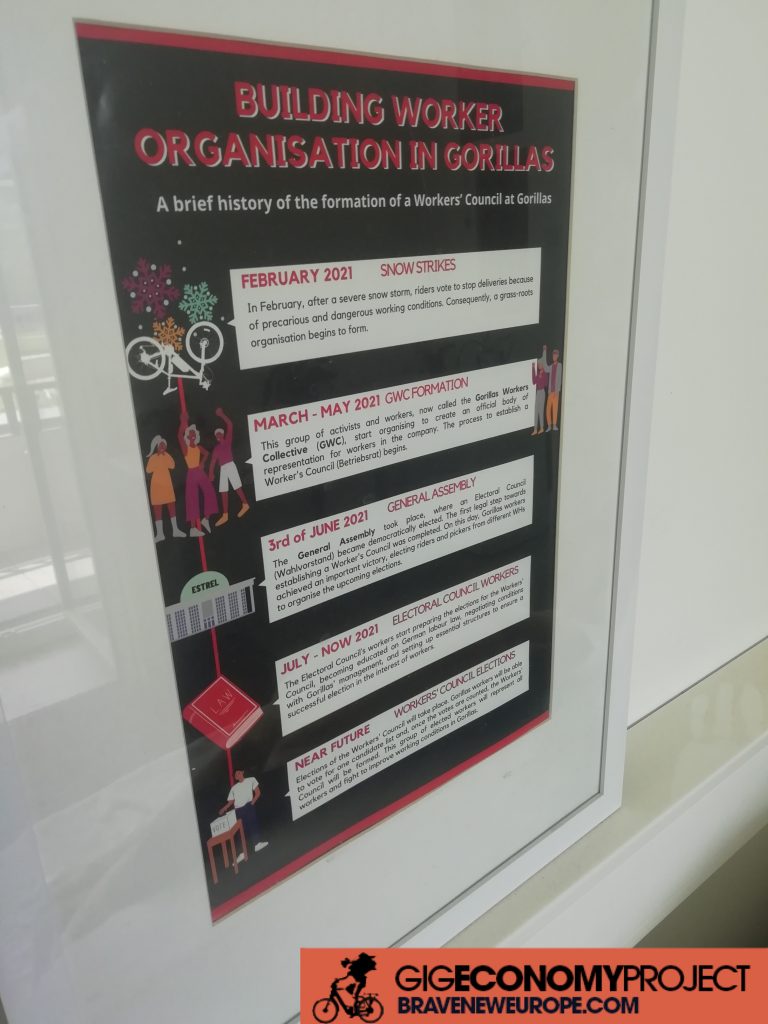

February 2021 was when the Gorillas Workers Collective began, at first with just a handful of workers. As the Collective built its strength, wildcat strikes began to be organised at warehouses. The strikes peaked in September-October, leading to the mass firing of hundreds of Gorillas workers in early October, turning a localised dispute into international news.

PODCAST: Gorillas Revolt: Interview with Zeynep Karlıdağ

Far from the mass firings defeating the movement, it simply lead them in a new direction. For Avik, who had only become a Gorillas rider in July, the firings had created a leadership “vacuum”.

“I wanted to help them, to be a supporter rather than a core activist. But then I realised there was this vacuum that needed to be filled, because things were in disarray a little bit in September-October during the strikes. I didn’t really sign-up for this but now I am knee-deep.”

The new direction was to go full steam ahead for establishing a Workers Council, which all sizeable workplaces in Germany have the right to establish and are officially responsible for representing the workforce on all key industrial relations issues. Multiple attempts by management, including a lawsuit, to block the Workers Council election were defeated, and the Council was established in December.

“We have achieved things with the Workers Council to an extent,” Avik, ever modest, says. “We saved a bunch of jobs, and at Alexander, the warehouse that’s been closed, if we didn’t have the Council they would have got a very bad bargain with the company, the compensation plan was only because we had the Council and a really good lawyer.”

Ronnie was one of the rider-organiser’s who was sacked in Gorillas’ mass firings, but just two days later he got a job at Getir and began organising there. He is now leading the battle to have a proper Workers Council established at the company after elections were allegedly hijacked by management. He had never planned to get involved in any kind of activism.

“I’m a student. This is the last thing I wanted to do in my life, but somehow I became part of this, and now I like it. At least I’m not a mule who just eats and works and sleeps.”

Migrant riders

Both Ronnie and Avik are from India. Another of the rider-organisers, Achmed, is a refugee from Syria of Palestinian descent. He shows me his residency card where it says ‘XXX’ next to ‘country of origin’. It’s impossible to understand the reality of food delivery in a city like Berlin without taking into account that many, possibly a majority, are migrants.

“She’s so scared that she is going to have problems,” Chiara, an activist with with ‘El Bloque Latinoamericano’, who is supporting Spanish-speaking riders at Gorillas with legal issues, says, referring to one South American rider who claims not to have been paid properly on three separate occasions.

“Because they are migrants that come with the Visa and they are scared that they will put their Visa in danger and will have to go back to their home countries,” Chiara explains.

This is a constant theme when I ask anyone who frequents the office about what the barriers are to organising in food and grocery delivery. Migrants have more to lose from being fired, and that fear is exploited by the platforms, who know that these workers will have less knowledge of their rights than German workers, and less ability to access them even if they do have the information. Avik, who’s Visa has run-out but seems typically unperturbed by this fact, says the problem is not an insurmountable one.

“Every worker gets to the point where it gets too much and they want to lash out at the company – every worker. And if you are there for them as a support system and say: ‘hey, this is what you have to do, and I can help you with this and this’, then it helps.

“But you have to do this very quick, otherwise the anger subsides, the frustration subsides. They start thinking that Germany is not for them, they are here on a Visa and they cannot fight like this, and even despite the rules being in their favour, they don’t know the rules so they have never learned about their basic rights.”

What next?

While the energy and dynamism of these rider-organisers is remarkable, one cannot help but notice that they all appear to be in their early to mid twenties, and many are also students. Food delivery is a job with an incredibly high turnover. Is this movement really sustainable?

That may depend on where the movement’s leaders decide to take it. The worker collective form of organising – much more informal than the traditional union structure – has proven itself to be forceful and adaptable, but that does not mean they have ruled out organising as a union going forward.

“I can only speak for myself, but I think it’s important to unionise eventually, but often when people think of unionising in Germany they say ‘we will enrol riders into the established unions because they need income, they need fresh blood’,” Avik says.

“Some of us think we need our own union, because these old bureaucratic giants in Germany, they are a hassle to deal with. There’s been a lot of criticism of them. I would prefer a union for the whole gig economy supply chain.”

Max, the Lieferando rider, has a similar way of thinking.

“I hope we will have an impact on existing unions so they transform and adapt, and maybe we find solutions that are compatible. But the disconnect is so huge that the solution for us has always been to build our own thing, to build our own structure, so I hope there will be enough workers who will have the motivation to do this.”

Whatever the future holds for the worker collectives of Berlin, they’ve shown that effective grassroots organising is possible in this sector. Regardless of the structure, that’s what trade unionism is all about.

“A lot of the stuff we are doing now was being done by trade unionists over 100 years ago,” Max adds. “We are doing basic union work to protect jobs, prevent wage theft; this is how unions started.”

To sign up to the Gig Economy Project’s weekly newsletter, which provides up-to-date analysis and reports on everything that’s happening in the gig economy in Europe, leave your email here.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment