Italy was the first country in Europe to experience a major Covid-19 outbreak and remains one of the hardest hit by the crisis. Giovanni de Ghantuz Cubbe examines the consequences of the pandemic for domestic Italian politics, as well as the country’s relationship with the EU.

Giovanni de Ghantuz Cubbe is a Research Assistant at the Mercator Forum Migration und Demokratie (MIDEM) and a PhD Candidate at the Technische Universität Dresden.

Cross-posted from LSE EUROPP

Covid-19 reached Italy in the second half of January. The real crisis began, however, between February and March, as the number of infections dramatically increased. How did the Italian political authorities react?

Following the official positions of the Italian government, we can identify two distinct phases. In the first one (fase uno), the government released a huge number of measures, decrees and administrative orders to limit the spread of the virus. Rigid restrictions were introduced, which included not only the lockdown but also restrictions on commercial and industrial activities. In this context, economic measures (such as the ‘Salva Italia’ decree) were also central. The goal was to help families and companies that were forced to suspend their work activities during this time. In phase two (fase due), which was officially announced by the government on 26 April, the Italian authorities initiated a gradual relaxation of the restrictive measures.

In both phases, the Italian government received substantial criticism. Although it declared a national state of emergency early (on 31 January), it did not act promptly and coherently in the aftermath. After an entire month of delays, Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte dispatched several decrees, yet the volume of these did little to help establish a consistent and clear approach to the crisis that could address the long-term consequences of the pandemic.

More precisely: the approach of the government was relatively effective in fase uno, where a short-term strategy for halting the spread of the virus was called for, but it was far less productive in the economic context and failed to offer real protection to those hit by the crisis. In addition, the coordination between the centre and the periphery was only partially successful: in many cases, there were contrasts between the central state and the regional authorities, as well as confusion over contradictory central and local regulations.

It is probably too soon to evaluate the concrete consequences of Italy’s management of the crisis. However, a closer look at public opinion data can provide us with some hints. Some data deals directly with Covid-19, while other information, like that addressing the public’s general appreciation of the government, does not. However, since Covid-19 has been the central – if not the only – topic on the political agenda of all parties and institutions for most of 2020, it is possible to read the variations in this second category of data as clearly connected to the pandemic.

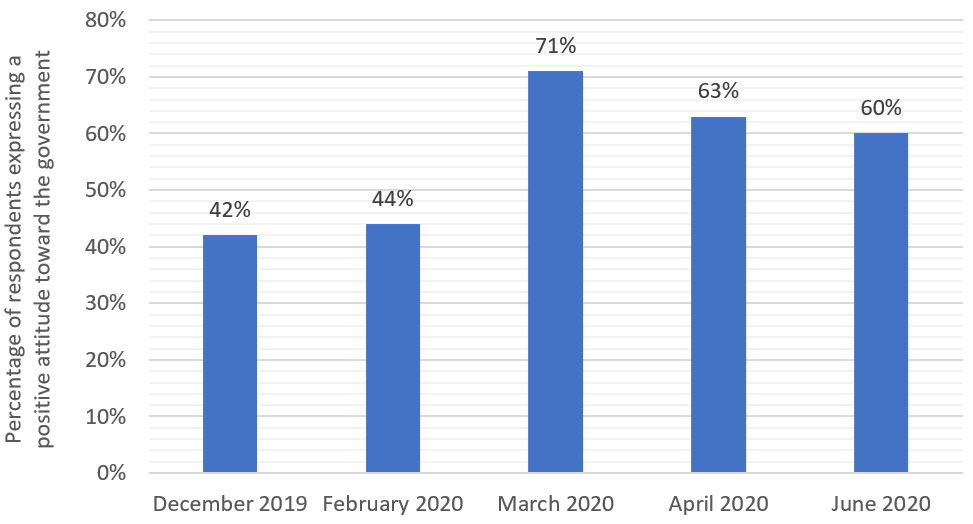

The first relevant fact we can observe is that Covid-19 initially helped to increase trust in the government (Figure 1). In December 2019, 42% of Italians had a positive opinion about the government. In February 2020, this percentage increased to 71%. In April, as phase two began, the trend changed: the percentage of those who saw the government positively decreased to 60% (June). In spite of this, the appreciation of the government remained much higher than in the pre-crisis period.

Figure 1: Percentage of Italian citizens with a positive attitude toward the government (December 2019 – June 2020)

Note: Figures refer to the percentage of respondents who selected a value of 6 or more on a 1-10 scale, with 10 being the most positive (Data for January 2020 are not available). Source: Demos & Pi

However, while Covid-19 had a positive effect on the way Italians viewed the government, it also caused other changes that could have less positive consequences. There are at least two relevant topics in this respect: first, domestic politics within Italy, and second, the country’s relationship with the EU.

Domestic politics

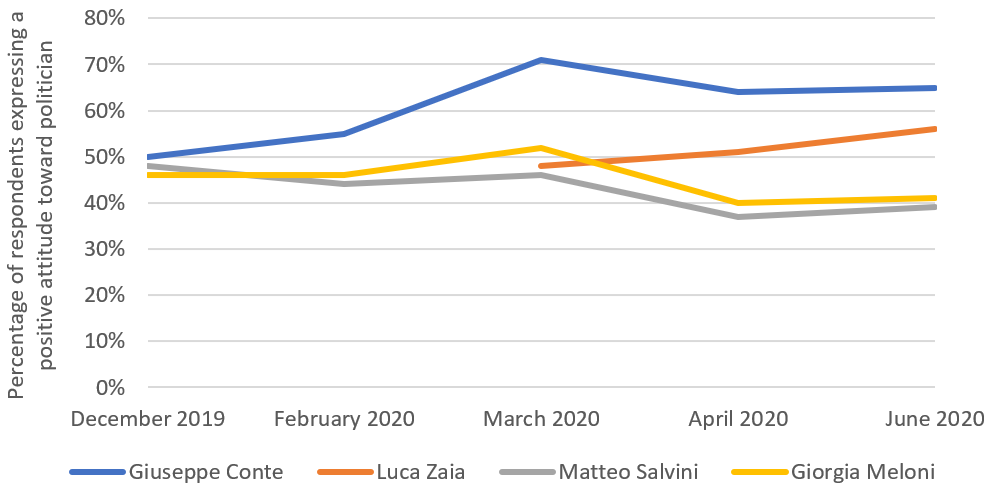

From December last year to June this year, we can observe important variations in the opinions of Italians regarding the most important political leaders of the moment (Figure 2). On the one hand, in line with the growing appreciation that Italians had for the government following the outbreak of the virus, it is not surprising that Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte strengthened his position as the most appreciated leader. On the other hand, there were unexpected changes on the right of the political spectrum.

Matteo Salvini, who has been one of the central figures in Italian politics for the last two years, experienced a decline in approval and was surpassed by Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the neo-nationalist Fratelli d’Italia, who brought her party from 7% in the polls at the end of 2019 to 14% by June this year. Moreover, Luca Zaia, an important member of Salvini’s Lega and President of the Veneto region, dramatically increased his standing thanks to his positions on the pandemic. He became the second most appreciated leader in the country and – in the words of the Financial Times – his newfound popularity “takes [the] shine off Salvini”.

Figure 2: Percentage of Italian citizens with a positive attitude toward selected politicians

Note: Figures refer to the percentage of respondents who selected a value of 6 or more on a 1-10 scale, with 10 being the most positive. Source: Demos & Pi

It is worth noting that the most popular leader, Giuseppe Conte, represents the central state, while the second most popular, Luca Zaia, is a regional politician. It is no coincidence, that these two leaders are rivals. Conte represents the government, while Zaia is member of the strongest opposition party (Lega). Indeed, the Lega, which has enjoyed huge success in many recent regional elections, governs different Italian regions and has enough power to challenge the government by advocating more agency and minimising the role of the central state. In other words, the party has been able to operationalise the historically difficult relationship between the centre and the periphery and take advantage of the pandemic to get political support from the people. It is not unlikely that the tension between the central government and the Lega will escalate in the future.

Italy’s relationship with the EU

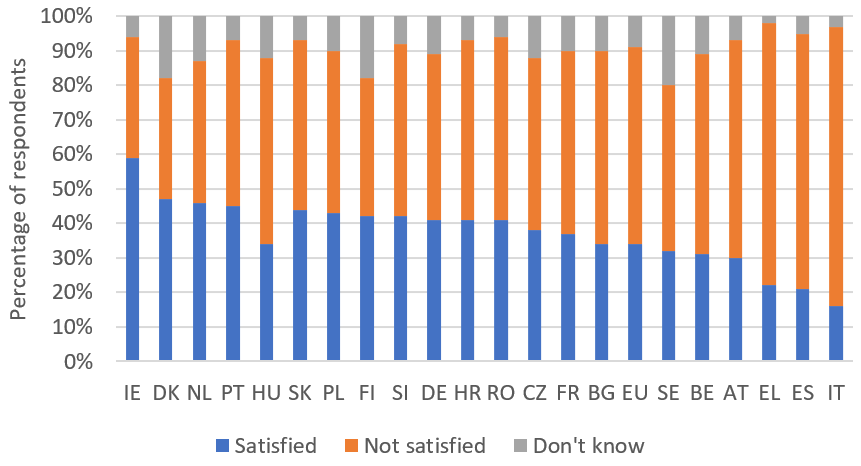

Covid-19 has had a negative effect on the opinions of Italians toward the EU (Figure 3). According to data from the European Parliament published in June, Italy has been the least satisfied European country when it comes to ‘solidarity’. Only 16% of Italians thought that the EU’s member states had provided enough solidarity to each other during the crisis.

Figure 3: “How satisfied or not are you with the solidarity between EU member states in fighting the Coronavirus pandemic?”

Source: European Parliament (June 2020)

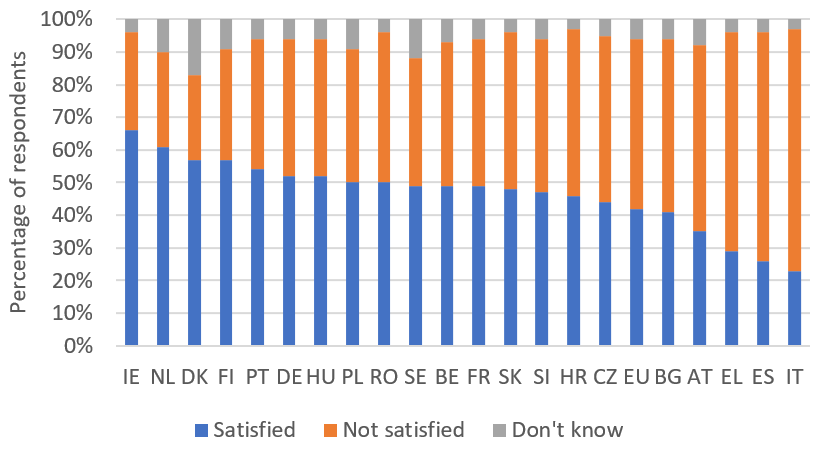

In the same way, Italy was the least satisfied country with respect to the concrete reaction of the EU to the crisis (Figure 4). Only 23% of Italians appreciated the measures the EU had taken to combat the virus.

Figure 4: “How satisfied or not are you with the measures the EU has taken so far against the Coronavirus pandemic?”

Source: European Parliament (June 2020)

In conclusion, Covid-19 has not caused a political crisis in Italy. However, it has clear potential to exacerbate existing conflicts, in particular the divide between the central state and the regions. Moreover, the pandemic has the potential to produce long-term negative effects concerning Italy’s relationship with the EU.

On the one hand, populist forces have tried to profit from the Euroscepticism of Italians. Following the dispute over ‘coronabonds’, Giorgia Meloni criticised the EU for trying to “profit from the difficulties” Italians were facing. Similarly, Matteo Salvini has called the EU a “viper’s nest” and announced his intention to “leave Europe, if necessary”. On the other hand, populists have not been the only ones to criticise the EU. Important pro-European Italian politicians such as Carlo Calenda have recognised that the crisis represents “an existential threat” for the EU. In this context, an eventual return of the virus this winter, which many scientists have predicted, could lead to huge political consequences.

Be the first to comment