Modern Monetary Theory has made incredible progress in the field of economics. Heikki Patomäki explains what it is, why it is important, and why it has become relevant.

Heikki Patomäki is Professor of World Politics of the University of Helsinki. He is also a civic activist and former member of the Board of the Left Alliance in Finland.

Modern monetary theory (MMT) has gained increasingly widespread academic and political interest. Its upward popularity trend seems to follow the formula “first they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win”. Or so, at least, an MMT-optimist might think.

What is clear is that MMT has reached the fight-stage. Neo-Keynesians like Paul Krugman have attacked MMT raucously in public and the theory has been the subject of constant debate. While most academic papers and books on MMT have so far been published in heterodox outlets, mainstream economists have begun to take MMT seriously, and perhaps especially so within central banks. One illuminating example of ongoing discussions is the October 2019 special issue of the real world economics review. It brings together some of the most prominent proponents of the theory, as well as post-Keynesian and other critics.

MMT has become popular with left politicians both in the English-speaking world and elsewhere. Well-known British media figure and author of several books Paul Mason and MEP Chris Williamson have supported MMT and worked closely with Jeremy Corbyn. In the United States, one of MMT’s leading theorists is Stephanie Kelton, Bernie Sanders’ adviser on the 2016 election campaign. Democratic Party’s rising star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has suggested that MMT-ideas could help fund ambitious health plans and a Green New Deal.

MMT has become relatively popular also in small euro countries such as Finland. MMT has reached mainstream publicity, not least thanks to young political economists from the University of Helsinki. The Money & Economy –blog created by Jussi Ahokas and Lauri Holappa in 2010 and their book “Taking Hold of the Money Economy” (2014) laid the foundation for widespread interest. Even though the blog was shut down in 2016 – partly due to aggressive and inappropriate attacks by mainstream economists – the story of MMT has since then gained further momentum. For instance, Holappa has continued to produce, among other things, a podcast series on similar issues and is now Li Andersson’s (Minister of Education and Chair of the Left Alliance) Economic Policy Adviser. Patrizio Lainà, the new chief economist at the Finnish Confederation of Professionals STTK, completed his PhD in 2018 on full-reserve banking. In 2018-19, Lainà has played a prominent role in bringing MMT ideas to the mainstream attention.

One of the key developers of MMT, Australian economist William (Bill) Mitchell, is among many other things an adjunct professor of political economy in Helsinki. Mitchell, whose popular blog is well known to many readers of this site, teaches in our annual course on Classical Political Economy and MMT. This is indicative of the interest in educating a new generation of political economists. In February 2019, I was involved in launching a new Macroeconomics textbook in London by Mitchell, L. Randall Wray and Martin Watts. The audience applauded loudly when Mitchell declared it to be the first non-fiction textbook in economics for years.

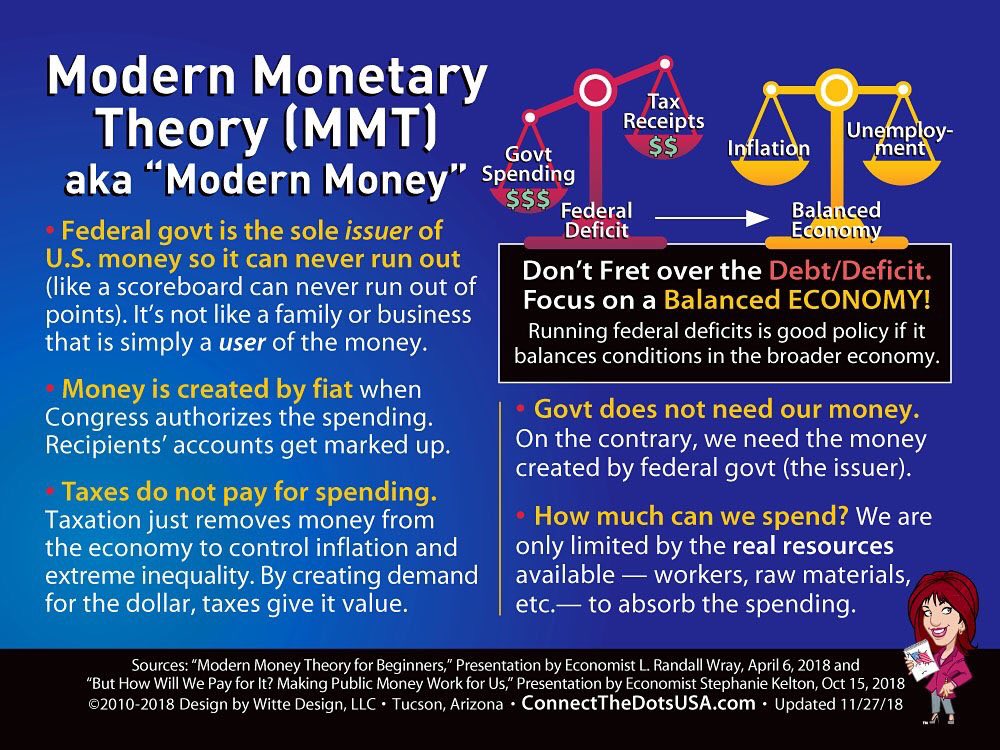

MMT is best known for its radical economic policy ideas. With states almost everywhere seeming to resort to austerity, lowering taxes, and selling their assets, MMT declares that a state can never run out of money if it is in debt in its own currency. With central bank funding, the state can, in principle, obtain whatever it wants. So there is no budget limit, at least not in any traditional sense. The restrictions stem from the real economy. When resources are fully utilized and full employment prevails, additional funding will lead to inflation. Attempts to purchase capital goods and other assets also has its limits, as it affects relative and absolute prices. Not everything is possible, but the space of possibilities is much wider than commonly thought.

MMT’s economic policy is based on seemingly simple theoretical reasoning. All money is essentially debt. The state designates the unit in which debts are to be settled and requires taxes to be paid in that currency. Money only requires a legal determination. Money does not require any precious metal or other commodity that money could obtain from a bank or central bank.

In addition, certain simple accounting identities apply to money flows. The state is at the forefront of the money hierarchy. It puts money into circulation through expenditure, while it withdraws it by taxing or selling bonds to the public. The private sector is saving and investing. In addition, there are imports and exports. Private banks too are capable of creating money, but they are still, by law and regulation, dependent on the central bank money and the interest and other claims imposed by the central bank. From the point of view of money flows, taxation is not needed to pay government expenditure, just to pull the extra money out of the circuit. Of course, taxation can have many other important goals, such as redistribution of income or health or environmental considerations.

If one accepts the basic concepts and theoretical starting points of MMT, the reasoning can appear very convincing. Strong rhetoric also drives the conclusion. MMT is a “modern” theory – unlike old-fashioned money theories. In terms of philosophy of science, the idea may be somewhat naive,iv but historically the attribute “modern” follows the fact that the world has shifted to the so-called fiat ( meaning “let it be done”, i.e. established through a mere decree) money only since the 1970s.

The United States unilaterally withdrew from the gold standard in 1971-73 (at that time other currencies were pegged to the dollar and through the dollar to gold). In the 2010s, the “unconventional monetary policy” of central banks has also contributed to the credibility of MMT. The US Fed, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of Japan have, at least implicitly and to some extent, shown that MMT’s assumptions about money creation and economic policy opportunities are true – though interpretations of the meaning and implications of this are, and probably will remain, controversial.

MMT rhetoric also includes the talk of “monetary sovereignty”. Sovereignty is a strong concept. In modern times it has been associated with absolute and exclusive power within a territory. The initially revolutionary 18th century concept of “people’s sovereignty” is, in turn, closely linked to both nationalism and the idea of democratic self-determination.

No wonder some critics have linked MMT to populism. MMT argues that money is basically free. Monetarily sovereign states can further any good public purpose as long as they stay within the constraints of the real economy, foreign trade and, to some extent, the money market (depending on the precise institutional arrangements). The elites may support economic globalization and complex international legal arrangements, but these arrangements restrict the freedom of sovereign states. MMT is on the side of the people and people’s self-determination. “People” here can mean either a democratic community of citizens or a nation in the sense of nationalism, or both.

Also in Europe, MMT has populist consequences, especially for the euro. MMT encourages the idea that states should withdraw from the euro in order to become monetarily sovereign. It also raises the question of whether they should be completely divorced from the EU, as it is appears that the EU has locked-in an economic policy based on austerity, privatization and short-sighted measures to improve external competitiveness. Corbyn’s ambiguous attitude towards Brexit is a logical consequence of these kinds of concerns, stemming also from the promises of MMT that sovereign states could become powerful again. Eventually the British “people”, relying on casual reading of right-wing nationalist tabloids, and tired of the Brexit mess, turned to Boris Johnson.

MMT theorists deny that their teachings have anything to do with exclusive nationalism, let alone racism or sexism. On the contrary, their criticism is that “the more the working classes turn to right-wing populism and nationalism, the more the intellectual-cultural left doubles down on its liberal-cosmopolitan fantasies, further radicalising the ethno-nationalism of the proletariat”. The aim of MMT theorists is to restore the value of democratic sovereignty, because progressive Europeanism and globalism are unrealistic projects. A cosmopolitan could point out that at least Corbyn was in no way “doubling down on his liberal-cosmopolitan fantasies”, and yet he fell. Moreover, the reason why he fell may have been precisely his (possibly MMT-inspired) hesitation about the EU.

In a short blog, it is not possible to properly discuss the economic theory of MMT. MMT can be interpreted as a theory that presents an alternative way of financing Keynesian economic policies, and in particular deficits (originally this approach was developed by Abba Lerner already in the 1940s). MMT focuses on stock-flow consistent models of financial flows in a capitalist market economy. It is not a theory of the development of the means of production, or of countries’ path dependent developments in the context of global economic processes, or, more generally, of the historical dynamics of capitalism. I think MMT’s view of money and the nature of money is more adequate than the neoclassical ahistorical notion of the development of barter and exchange economy. Yet not all money is debt. Money may evolve also partly independent of the state and its taxation. The MMT interpretation of the history of money is further limited by a certain amount of hindsight and by reading our contemporary categories into the past, where they did not exist.

Accounting identities are not sufficient as a basis for economic analysis. An adequate analysis requires a causal explanation of institutions (such as money) and historical processes (such as accelerating inflation). For example, there is no point at which production capacity is fully utilized, since every investment implies also an addition to and qualitative development of production capacity. Even when there remains unemployment, bottlenecks can start to accelerate inflation. In turn, investments also depend on social structures. For example, the distribution of income and wealth, the tendency of the upper class to conspicuous consumption, and state capacity to tax – all these influence the amount of real surplus available for real investment. Inflation can also be the result of unresolved acute income distribution struggles and mistrust in institutions, for example due to corruption and inequalities. Argentina is a good example of what these mean.

In addition, as MMT developers openly acknowledge, the positioning of a country in the division of labour and processes of the world economy largely determines the importance of its money issuance. From this point of view, the United States is a special case because the dollar is the world’s main reserve currency and preferred medium of exchange. There seems to have been enough demand for dollars for any practical purpose. But is the US an example of better? From the perspective of democratic left, it can be difficult to justify the United States as an ideally “monetarily sovereign” state whose economic policy is based on the rational promotion of the interests of the “people” rather than the elites. The hope of MMT supporters must thus be placed on the future prospect of an MMT supporter leading US economic policy and trying a different kind of economic policy. Still, Bernie Sanders, for example, pursues seemingly “utopian” projects such as universal healthcare and free higher education that remain, to a large degree, a part of everyday lives in a country such as Finland, despite decades of neoliberalization.

In spite of these and other reservations and doubts, I find it clear that MMT has been able to demonstrate that the money issuance is of great importance in contemporary capitalist market economy and that the prevailing doctrine of financial constraints on economic policy is misleading. The positive teachings of MMT are also independent from its populist-leaning rhetoric, that is, from the loaded use of words such as “modern” or “sovereign”. Instead of modern monetary theory, we could talk about neo-chartalist theory; while the term “monetary sovereignty” could easily be replaced by “relative monetary autonomy” (the precise meaning of which depends on many contextual features). Nor is the doctrine in any way intrinsically linked to a single nation or state. As Konsta Kotilainen, a doctoral researcher in Helsinki, explains, the creation and control of money produce powers that can be organized institutionally in many ways, including cosmopolitan.

Money is not only an institution but also a form of power; and this power can be organized on many levels and at each level more or less democratically. The ability to create money is linked to the notion of “sovereign” in conventional modern law and politics only in a contingent way, that is, it is not necessary but depends on many things. The figure below illustrates some possibilities.

|

public issuance of money |

Sovereign |

Non-sovereign |

|

State/nation |

Egypt, Japan |

Finland before 1917 (when it had its own central bank and currency, but was part of the Russian Empire) |

|

Regional federation |

Brazil, United States |

European Union |

|

Global |

A world state as a replicate of existing sovereign states? |

Keynes and Stiglitz proposal for an International Clearing Union (ICU) |

Another central argument of MMT is that monetary autonomy requires floating exchange rates, which have been gradually adopted across the world since the 1970s. I think this connection is also contingent. Relative autonomy is dependent on one’s aims and priorities and is compatible with many international or global monetary systems. Indeed, there are many options other than strictly fixed or totally flexible rates. In their pure form, flexible or floating rates require market-based currency exchange and therefore also freedom of capital movements. MMT theorists, however, typically take a positive view on controlling capital movements, which seems somewhat contradictory to me (even though I tend to agree about the need for such controls).

In any case, there are many alternative ways to organize currency exchange. For example, in the 1970s a group of European countries agreed on a “currency snake in the tunnel”, which set limits to market movements (also vis-à-vis US dollar) and was a combination of a regulated and market-based system. I have advocated – and remain in favour – a system in which foreign exchange is subject to a two-tier tax and regulated in a variety of ways. This model is also compatible with Keynes’s and Joseph Stiglitz’s International Clearing Union (ICU) proposal. The idea is to create a world central bank money also for the purposes of global common good and to regulate trade balance surpluses and deficits globally through the balance sheets of a world central bank. Stiglitz suggests that the powers of creating global money could be directed toward helping to address climate change and its consequences as well as to bring about global social justice.

The combination of a currency exchange tax (or, more generally, a financial transaction tax) and the ICU can be seen as the “second best” option only. As James Tobin emphasised already a half-a-century ago, at least for the time being a taxed and managed system remains a more realistic option than creating a real world currency. The Tobin tax would be a step towards global taxation, however, thus opening up interesting possibilities from an MMT-perspective as well.

Be the first to comment