The cost of affordable housing in New York City

J. W. Mason is Associate Professor of Economics at John Jay College, City University of New York and a Fellow at the Roosevelt Institute

Cross-posted from J. W. Mason’s Blog “Money and Things”

With the failure of Eric Adams’s last-ditch effort to stack the Rent Guidelines Board (RGB), Mayor Zohran Mamdani is now in a position to fulfill his promise to freeze the rent.

The nine-member RGB sets maximum rent increases for New York’s million-plus rent-regulated apartments, determining rents for over half of the city’s renters. They are tasked with balancing the interests of tenants and building owners, considering a wide range of factors including the cost of operating rent-regulated buildings, the cost of living for tenants, and the overall state of the housing market. In practice, they have wide discretion. The RGB delivered a rent freeze — a 0 percent increase in regulated rents — three times during the De Blasio administration.

Most discussion of rent regulation in New York City focuses on the legal intricacies of who, where, and when the RGB guidelines will bite. But this risks losing sight of the bigger-picture questions about the financial terms on which housing is bought, owned, and sold in New York City—terms which may have to fundamentally change to make affordability possible in New York City.

To understand the implications of a rent freeze, we need to think about the broader economics of housing in New York. Any discussion of rent regulation has to grapple with the fact that owners of residential buildings pay most of their rent earnings not on maintenance or operations, but to service their debts to their creditors. With the kind of leverage typical for investor-owned residential buildings, any significant slowing of rent growth is likely to see many building owners unable to make their mortgage payments.

The great majority of residential buildings have rental income well above their operating costs, and they could be profitably operated even with rents much lower than today’s. So in principle, there is space for the RGB not just to freeze the rent, but roll back regulated rents by some significant percent. The big obstacle to a mandated rent reduction is not the real costs of providing housing, but the financial commitments inherited from the past. A building underwater on its mortgage is unfortunate for the owner; it can be disastrous for tenants. A plan to freeze regulated rents, or even to limit them to modest increases, needs to be combined with a plan to ensure a quick resolution for apartment buildings in financial distress.

Waiting for a market solution to this dilemma through the bankruptcy courts would be disastrous for tenants, who would bear the brunt of cost savings in the form of decaying living conditions while landlords wait for a better deal. Instead, the city’s plan to freeze or reduce rents must be combined with a quick resolution for apartment buildings in financial distress. This resolution must take account of the major dynamics that shape the rental market in the city—high rent burdens, inadequate investment in previous decades, and the distinct circumstances of landlords controlling old buildings versus developers looking to build new ones. After a rent freeze, true housing affordability will call for a model of alternative, including public, ownership.

The rent-stabilized market

It’s easy enough to predict the argument against freezing the rent—without rent increases, many building owners will face financial distress, leading to deferred maintenance or abandonment. A recent piece in The City describes how property owners have struggled to make mortgage payments and cover operating expenses:

Every month, Langsam Property Services collects dozens of rent checks from two buildings it manages in The Bronx. But that’s not enough to cover the mortgage and operating expenses. So every month, the buildings’ owner sends another check—for at least $30,000, just to meet the mortgage.

The kinds of buildings…where all or almost all of the apartments are rent regulated…face extreme financial distress. Rent increases failed to keep up with costs for most of the last decade, and changes to state law in 2019 made it virtually impossible to renovate vacant units and raise the rents, putting such landlords in a bind…A four-year rent freeze could result in the kind of abandonment that happened in the 1970s.

It’s important to take these concerns seriously. I don’t think the landlords quoted here are lying when they describe their difficulties paying their mortgages. But we should distinguish between debt service and other costs. Operating and maintenance costs reflect the actual costs of operating a building in the city. Debt service, on the other hand, reflects how much the current owner paid for the building.

Combining these two sets of costs is common in discussions of rent regulation. Another recent story, for instance, quotes the executive director of the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development: “You can’t continue to run a building without paying the mortgage and without paying your insurance.” Insurance is indeed a cost of running a building, but the mortgage is not. At most, it is a cost of owning it.

As we think about the economics of rent regulation, we should keep this distinction clear. Operating and maintenance costs are necessary costs of providing housing; mortgage payments are not. Essentially none of the debt owed by owners of rent-regulated buildings is construction loans, and very little of it is financed capital improvements. The cost of servicing that debt is not part of the cost of providing housing. It rather reflects how much the owner has borrowed against it. The problems faced by owners of rent-regulated apartment buildings look very different in this light.

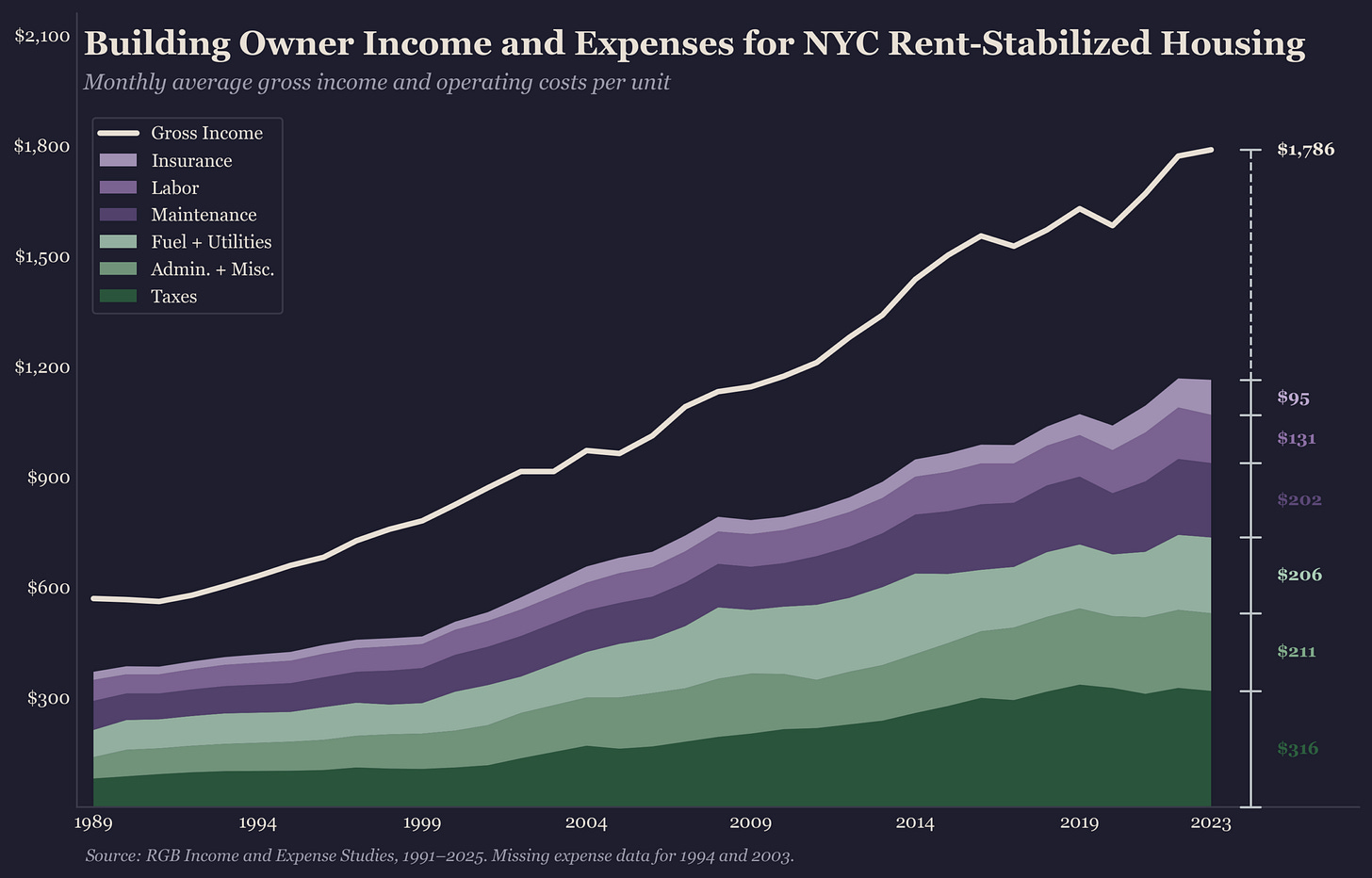

There is plenty of data on the incomes and expenses of residential buildings in the city, in particular the detailed (though not always complete) records of the New York City Department of Finance (DOF). Research and advocacy organizations like the Furman Center and the Community Service Society regularly put out useful reports based on this. For present purposes, the RGB’s annual Income and Expense Study, based on the DOF data, is enough to give the broad picture.

In buildings with rent stabilized apartments, reports the RGB, rent averaged $1,600 per unit; landlords on average collected another $200 per unit from other income sources—parking, retail space, cell-tower rent, and so on. Maintenance and operating costs, meanwhile, averaged a bit less than $1,200 per unit, including taxes (a bit over $300 per unit) and insurance (almost $100 per unit, and the component that has increased most rapidly in recent years). For the average rent-regulated building, net income is around $600 per unit, about 50 percent above operating costs.

This relationship between costs and income seems fairly stable over time, albeit with some short-term ups and downs. Over the past two years, landlord income has increased by 15 percent, while costs have increased by only 10 percent. But this was in large part making up for the pandemic period, when income increased more slowly than rents. Over the long run, the two have kept pace almost exactly—over the past twenty years, landlords’ incomes have increased at an average annual rate of 3.8 percent, while their costs have increased at 3.7 percent.

These averages mask a great deal of variation across individual buildings. Still, over 70 percent of buildings with rent stabilized units had operating and maintenance costs less than 80 percent of income, and fewer than 10 percent had operating and maintenance costs greater than income. This minority of buildings are a serious concern, and their numbers do seem to have increased somewhat in recent years, but they remain a fraction of rent-regulated buildings.

Yes, if rents on stabilized units were frozen forever, there would come a point when operating costs exceeded income for an increasing share of buildings. But why are building owners facing distress today? The answer in most cases is that they borrowed too much to buy buildings at inflated prices, based on an expectation that rents would rise faster than they actually did.

Landlord economics

The price that an investor will pay for a building, and the size of the mortgage that bank will give them to do so, is a function of the rent that the building is assumed to generate in the future. Lenders will typically accept a debt-service ratio of 1.25, and some will go as low as 1.1, meaning that they will lend as long as the expected rental income net of operating costs is 1.1 to 1.25 times as great as the payments the mortgage requires each month. To say that a building’s net rental income is 1.25 times its debt service costs is the same as saying that 80 percent of rental income after operating costs will go to mortgage payments, if the building performs as expected.

Furthermore, investors in multifamily buildings often refinance in order to extract equity when a building has increased in value. Say a building is valued at $10 million and is currently carrying a mortgage of $7 million, meaning that the owner’s equity is worth $3 million. If a lender would be willing to accept the building as collateral against $8 million of debt, the owner can take out a new mortgage, reducing their equity to $2 million and leaving them with $1 million in cash—which they will presumably put toward acquiring another building.

This sort of “cash-out” refinancing was seen as a troubling aberration when it became popular among homeowners during the 2000s housing boom. But for real-estate investors, it is an established business practice—borrowing against one’s existing properties is the easiest way to finance the acquisition of new ones. From an investor’s point of view, a building carrying a smaller mortgage than what lenders would accept is money left on the table. Careful observers of the housing market believe that this kind of equity extraction may account for the bulk of the debt carried by rental properties in the city.

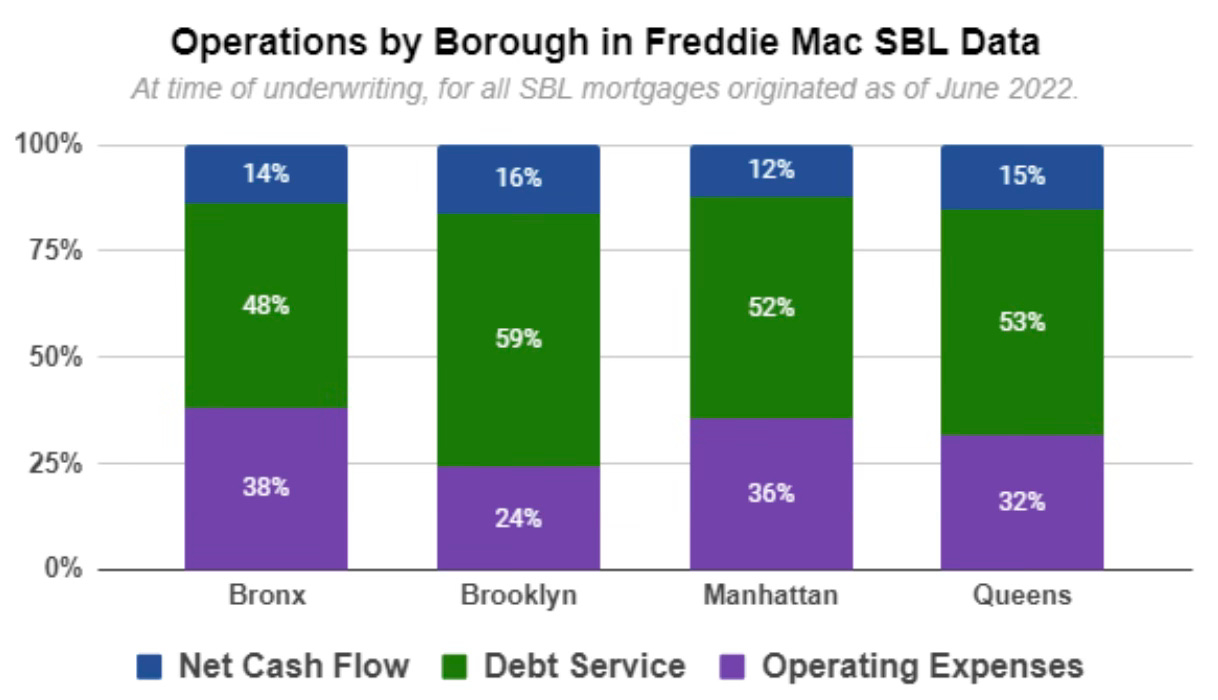

This means that even buildings that have not changed hands in many years often carry mortgages close to the maximum debt-service ratio that lenders will allow. Research by the University Neighborhood Housing Program based on data from the government-sponsored enterprise Freddie Mac (which purchases a large share of mortgages on New York apartment buildings) finds that residential buildings in the city, on average, pay out about 80 percent of their net operating income as interest payments. This suggests that building owners are normally operating close to maximum leverage. For most buildings in the Freddie Mac sample, interest payments are a larger cost than all operating expenses put together.

Whenever rents rise more slowly than expected when a building was purchased or refinanced, there is a good chance that the owner will be unable to meet their mortgage payments, even if rental income is still comfortably above operating costs—as is the case in the majority of buildings.

Rent growth below buyers’ (and lenders’) expectations is a particular problem with buildings that were bought or refinanced prior to the 2019 reform of the New York State rent laws. These investors hoped to win substantial increases in rents for regulated units or remove them from regulations entirely, using a number of loopholes that allowed landlords to kick out their current tenants and rent out the units at a higher rent. Since the 2019 reform, this is nearly impossible. As a result, many buildings purchased in the 2010s cannot generate income commensurate with what was paid for them.

To be clear, the rent reforms were a major positive step for housing affordability. The expected increases in rental income could only have been realized, in most cases, by evicting current tenants and attracting higher-income ones. But losing the possibility of replacing current tenants with higher-paying ones has left the owners of these buildings in a financial hole.

A future with lower rents?

This overhang of overvalued, overmortgaged buildings is presumably a major reason why there has been so little activity in the market for multifamily buildings in recent years, with the volume of sales less than a third of what it was a decade ago. How then should we think about landlord complaints—many of them genuine — that a rent freeze will leave them unable to service their debts?

First of all, it should be clear that if buildings’ rental income is inadequate given their debt payments, the reason is lower than expected rents—not rent regulation per se. If an Abundance-style program of supply-side reforms delivered enough new construction to substantially bring down rents, building owners like those quoted in The City would face the exact same difficulty. Any slowing of rent growth will create financial distress for building owners who borrowed on the expectation of rising rental income.

There might be steps the city can take to reduce costs for building owners—insurance being the most promising avenue—but the potential savings are limited. Major improvements in housing affordability will entail reducing rental income for existing buildings. At the end of the day, tenants’ housing costs are owners’ incomes; lower gross income for landlords is just the flip side of more affordable rental housing. The housing agenda must then explicitly include a strategy for property owners whose debts cannot be paid in an environment of lower rents.

One might ask, why does the public need to be involved? Perhaps this is an issue to be left to owners and lenders. Either the bank writes down the loan, or else it forecloses, and the building is sold to someone else at a more realistic price. The trouble is what happens during the transition: the foreclosure process can drag on for years, and financially distressed owners are likely to prioritize mortgage payments over maintenance and upkeep, allowing buildings to fall into disrepair at great cost to their tenants and to whomever ends up owning the building. Landlords will stop paying for gas before they give up control of their buildings.

The lower the rent increases allowed by the RGB, the more urgent code enforcement becomes as a complement to housing affordability measures. Otherwise, what landlords give up in rent increases, they will try to claw back in reduced maintenance. At the same time, a successful affordability policy means that many buildings will be worth less than what their owners paid for them. Someone is going to have to bear those losses. It’s important to proactively shape how that happens, rather than wait for the market to work itself out.

One approach would be for the city to work with landlords and creditors to negotiate mortgage write-downs in return for hard commitments to a higher standard of maintenance and improvements. The response to the failure of Signature Bank could be a model. Signature was a major lender for multifamily buildings in New York; a considerable part of its portfolio of loans to owners of rent-regulated apartments ended up in the hands of the Community Preservation Corporation (CPC). CPC agreed to loan modifications in return for clear commitments by landlords to address building and habitability code violations. The city could push other holders of mortgages on underwater buildings to make similar deals.

CPC had the big advantage of already owning the loans. As a third party, the city government might struggle to bring lenders and building owners to the table. Another option, promoted by the mayor’s new Director of the Office to Protect Tenants, Cea Weaver, would be for the city to move aggressively to take ownership of buildings that can’t make their mortgage payments.

There are also a nontrivial number of buildings where operating costs exceed rental income. These are especially common in the Bronx, where past underinvestment may have contributed to today’s costs, and many are already owned by nonprofit Community Development Corporations (CDC). CDCs have a fundamentally different business model than the investors who own most of the city’s rental buildings. They use far less leverage, and, while almost all are rent-regulated, they tend to charge rents below the legal maximum.

The economic challenge here is quite different from that of most buildings in the city. The problem is less financing, and more the very low incomes of families living in these buildings, combined in many cases with underinvestment and neglect by prior owners. The solution here will involve operating subsidies. While the details of this are beyond the scope of this piece, subsidies to building operators are generally to be preferred to subsidies to tenants, which may be captured by landlords in the form of higher rents. The city’s Multi-Family Water Assistance Program is a good example of a targeted subsidy to affordable housing operators.

The situation of these genuinely distressed buildings should not be confused with that of the larger group of rental buildings where net income is positive, but insufficient to cover mortgage payments. In these cases, we must avoid two outcomes. The first is weakened rent regulations, which would make tenants pay for landlords’ speculative overborrowing. The second is allowing buildings to remain for an extended period in the hands of owners who will eventually lose them. If the current owner is going to give up the building, that needs to happen as quickly as possible. The threat of forced sale can be helpful to incentivize a quick settlement, even when it is not carried out.

Expanded public ownership is not just a long-term vision; it is an essential part of the solution to an immediate problem. The fundamental issue is that landlords are being squeezed by high debt costs from one side, while they aren’t able to charge higher rents, and they can’t cut costs without sacrificing habitability, which effective code enforcement will prevent. Under these conditions, some building owners will indeed face unsustainable losses.

The role of public ownership, in this sense, is to provide an escape valve, a way for owners to exit their position without running the danger of an extended foreclosure process. The pressure on landlord incomes will be a source of great anger and scare stories in the press, but this is also precisely what gives the city leverage to force creditors to write down debt and move toward alternative models of ownership. It is worth pursuing genuine savings that the public can deliver, like pooling insurance.

It would be a big mistake to simply offer relief to stressed landlords by exempting buildings from the rent laws. That would only pass the costs off to tenants without resolving the structural problem that undergirds the rental housing market—the mismatch between debt loads and affordable rent growth.

Even worse, allowing higher rents in response to financial distress would give other landlords hope that if they hold out longer, they will be able to avoid a resolution. Any hint of flexibility on the rent freeze could leave us in the worst of both worlds—a situation where building owners cannot pay their bills, but won’t give up ownership because they are hoping for higher rents in the future. An ironclad commitment to the rent freeze and to stringent code enforcement is essential to bring landlords and creditors to the bargaining table.

Landlords vs. Developers

The city’s leverage in negotiations with private landlords will implicate the broader politics of housing. Building more housing was a central plank of Zohran Mamdani’s platform. For the foreseeable future, that will require private developers and contractors, who control the specialized expertise, labor and resources required. NYCHA, for all its challenges, successfully operates buildings for over half a million New Yorkers. But it doesn’t put up new housing, nor is there yet any non-profit developer equivalent to the CDCs that manage so much of the city’s affordable housing. So if the city is going to gain more affordable housing, it has to offer sufficient returns to the businesses that will put it up.

The case of private landlords is different. The market rent for apartments in New York does not reflect the cost of construction; rather, it is determined by the balance between the demand for housing and an effectively fixed supply. Market rents in much of the city are significantly higher than the cost of maintaining and operating buildings. Unlike the payments to developers and contractors, most payments to landlords are rents in an economic sense.

In a recent post, the conservative journalist Josh Barro describes the emerging Mamdani-DSA housing policy mix as capitalism for developers, communism for landlords. He intends this provocative phrase to express skepticism about the coherence of the program. But it seems to me that, from an economic perspective, this is exactly the combination we want.

From the standpoint of private business, to lay out $10 million to build a new apartment building that you will operate or sell for a profit or to buy a similar existing building for $10 million may be roughly equivalent options. But from a social perspective, these options are completely different—one is creating something valuable for society, the other is trying to divert existing value in your direction.

Can we really split developers and landlords in this way? After all, even if very few buildings are owned by the same entity that developed them, the developer’s profit comes from selling the building. If old buildings generate lower net incomes and sell at lower prices, won’t this discourage new development?

Politically, the alliance between developers and landlords may be difficult to break. But economically, it is absolutely possible to reduce the rents on old buildings without meaningfully reducing the incentive to build new ones. The reason is discount rates.

Housing is distinct from other commodities in its lifespan: the median age of a New York apartment is about eighty years. A building’s major costs—construction and land acquisition—were often incurred decades ago. This means the link between price and production costs is much weaker.

Economists conventionally count interest costs as part of the cost of production. This is reasonable for a business that issues debt to finance inventories or relatively short-lived capital goods. But it is emphatically not the case for housing in an older city like New York, where the vast majority of debt owed by landlords was incurred to finance ownership of a long-existing building rather than the construction of a new one.

Looking at it from the other direction, a typical investor in a new housing development might expect a return of 20 percent; lenders accept an interest rate that might be on the order of 8 to 10 percent. These returns are equivalent to discount rates; to say that a developer requires a return of 20 percent, is equivalent to saying that they put a value of about 80 cents on a dollar of income a year from now. At a discount rate of 8 percent, a dollar fifty years from now has a present value of about 2 cents; at a discount rate of 20 percent, it’s worth one-hundredth of a cent. This means that the rent a building will command decades from now plays essentially no role in the decision of whether it’s worth building today.

No rational investor would pay money to build an apartment that will come into existence decades from now. But the nature of real estate is that ownership today implies ownership into the indefinite future. If you put up a building in order to rent it out next year, the building ten, twenty, one hundred years from now comes along for the ride. Given the age of the city’s housing stock, this means that the rent paid in a typical New York apartment has no relationship to the building’s construction costs; those were paid long ago. To the extent that landlord income exceeds the operating and maintenance costs of the building—and, again, it does on average by a margin of 50 percent—then that rent is also a rent in an economic sense: a payment in excess of the cost of producing something. The fact that these economic rents are not necessarily captured by the current building owner does not change this.

In this sense, buildings are a bit like intellectual property, which also lasts longer than the economic horizon of the businesses that produce it. The economic argument for rent regulation is a bit like the argument for limiting patents and copyrights to a finite period.

For housing in a city like New York, there is no reason to think that the market price provides a useful signal about the balance between value to consumers and cost of production. What, then, is a reasonable rent for older residential buildings? Arguably, it should be limited to operating costs plus a moderate margin. Rent payments above this are simply a transfer from tenants to building owners (and their creditors).

Housing as a public utility

Real estate investors generally expect much of their returns to come from capital gains—an increase in the property’s market value rather than the rental income it generates. Since buildings are normally valued at a multiple of their rental income, this means that owners expect not just high rents relative to operating costs, but steadily rising rents over time. If rent growth shifts onto a more affordable trajectory, owners will see lower returns, even if their buildings continue to generate a positive income for them. Under these conditions, the kinds of private investors who currently own much of New York’s housing stock might prefer to not.

This is not an argument against moving in that direction. But it is a reason for thinking carefully about how the losses will be shared out, and how to ensure that lower returns for investors and creditors do not hinder the ongoing payments that are needed to operate housing—utilities, maintenance, and so on. Public ownership is an essential tool here. So too is tenant organizing, including demands that landlords open their books as a condition of any kind of relief.

On January 1, after Mayor Mamdani was sworn in at the old City Hall subway station, the Washington Post crowed that his midnight inauguration was actually a tribute to private industry, since the city’s first subway system, the IRT, was built by a for-profit company.

It is true that New York’s first subway system, the IRT, was privately owned. But one could read this history in a different way. City government did not take over the subways out of any ideological commitment to public ownership. Most city leaders in the early twentieth century (the IRT-hating John Hylan excepted) were happy to leave the subway in private hands. The problem was that a comprehensive system with affordable fares became incompatible with acceptable returns to private investors. The need to rescue the private system from financial crisis was why the city took over, and the state later established the MTA.

Perhaps decades from now, we will be able to tell a similar story about housing. Today, New York City’s rental market is defined by two colliding forces: tenants’ need for affordable rents, and landlords’ need to repay their creditors. Only public ownership offers an escape from the mounting pressure. If New York moves towards a model of social housing, it will be because public ownership is consistent with stable rents in a way that ownership by private investors fundamentally is not.

Be the first to comment