For all non-economists. This is a brilliant introduction to the fallacy of “How do we pay for it”. Simple and clear.

Jack Mosse holds a PhD from the Media and Communication department at Goldsmiths University and has further degrees in Philosophy and Social Anthropology. His brand new book, The Pound and the Fury is published by Manchester University Press.

Cross-posted from Positive Money

While working towards my PhD I came across Positive Money’s work and it drastically altered the way I was thinking about my research. It helped provide the evidence and rationale that I needed to make my argument. I had spent time talking to hundreds of people about the economy, as I wanted to explore how we, as a society, think about our economy. I was midway through this research, and knew that there was something wrong with the underlying conception of the economy that almost all my interviewees had (I spoke with a broad range of people – financers, civil servants, financial journalists, and the inhabitants of one of the UK’s largest housing estates), but I didn’t feel solid enough in my understanding of how our economy works to articulate what it was. Discovering Positive Money and reading some of the texts they promote changed that, it allowed me to clarify, in my mind’s eye, what was wrong with the visions of the economy I was witnessing, and gave me a way of writing about the myths that prop our economy up and how we can strive to see past them. The PhD has become a book, a small adapted section of which follows:

As I spoke to more and more people it became evident that one assumption was dominating and framing how the people I spoke to thought about the economy. I took to calling this ‘the pot of money’ myth. It was pervasive in almost all my interviews, but was most clearly expressed on the council estate through the notion of immigrants or refugees subtracting from the national pot.

Take, for instance, Sandra, a grandmother who talked to me in a medical centre’s waiting room as she and her grandson waited to be seen, she even used the pot metaphor:

“They’ve let too many refugees in really. There’s

not enough for the true English people. They’ve

got to think of their own in the country, people

that have been paying taxes and things like that

before they bring other people in. I mean, I feel

sorry for the refugees, but there again, you can’t

feel sorry for everybody. You’ve got to help our

country, we’ve got people living here who have to

go to the food bank … they’ve let so many immigrants

in they don’t know what to do, they haven’t

got enough money in the pot to give them.”

Sandra’s words are indicative of the conversations I had with people on the council estate. They clearly show a conception of the economy as something like a national pot, that some people pay into through tax and some people take out through claiming benefits. In different ways, I found similar notions of the economy, at the other spaces I looked at (the civil service, London’s financial district, the media) and other research, which has been undertaken on a far grander scale to my own, also finds that we broadly conceive of our economy as something that can be paid into or taken out of, something like a household budget, or as I describe it, a ‘pot of money’.

There are significant political implications that stem from viewing the economy as a ‘pot of money’. The vision distracts from the institutional structures that shape how society functions. Instead, it demonises or praises individuals and groups who are seen as paying in or taking out from the national pot. It’s also a vision that limits political and economic imagination by binding us to the idea that we are always restricted by the amount of money in the pot, and that we should always be looking to ‘balance the budget’. Furthermore, it does not concur with the reality of how our economy functions. The first point to make is that governments, as well as private banks, create money out of nowhere. This is discussed at length in the book but, given this fact, the idea that there simply isn’t enough money in the pot doesn’t make sense. Money can always be printed, or typed – another zero can always be added.

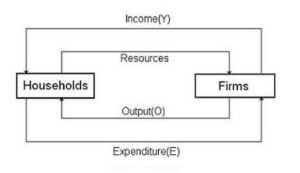

So, while the aim for individual households and businesses might be to bring in as much money as possible, a nation’s economy is a different entity altogether. Not only can money be magicked up out of thin air, a quick skim of any introductory textbook shows that the agreed-upon foundations behind academic economics presents the economy as something very different to a pot of money. To understand this, we can look at a ‘circular flow’ diagram: this is one of the first things taught in introductory economics courses and versions of it can be found in all mainstream 101 textbooks.

The version of the circular flow diagram shown in Figure 1 simplifies the economy and imagines that it consists of just individuals and firms: the firms employ the individuals, and the individuals buy the goods the firms produce with the wages the firms pay them. This is self-perpetuating, as the money the firms get from the individuals buying their goods goes back into wages, which are then spent on more goods …

Figure 1: Mosse, J. 2021, The Pound and the Fury, Manchester University Press – Page 27

Of course, in reality it’s a bit more complicated as there are other actors (e.g. the state, the financial sector, other nations’ economies), but the basic principle of what it is doesn’t change. It is a series of relationships between mutually dependent actors, where money, goods and labour flow in a circular manner. It is not a pot of money that can be filled up and emptied. What economists disagree on is how this system should be managed. And two approaches have dominated theory and policy for the last hundred years or so. Both of them run counter to the notion of the economy as something akin to a pot of money.

Keynesianism argues that when this system isn’t working properly and we have high unemployment – which means individuals don’t have the money to buy the firms’ output, and everything is starting to slow down – a big dollop of cash introduced by the state can get things moving again. Pouring new money into the system will allow households to buy goods, which will allow firms to employ them again, and the system of mutual dependency kicks back into gear. However, this cash injection needs to happen when enough people are unemployed and resources are not already being used. If the system is already at full productive capacity (which, in reality, it almost never is), and the state just dumps a load of cash on it, all that will happen is that wages will go up along with the price of goods, meaning people will be paid more but everything will cost more – the amounts of goods being produced and number of people in employment will not be meaningfully effected. This concept is known as inflation.

Monetarism – the school of economic theory that took over from Keynesianism and has dominated policy in the past 40 years or so – posits that government spending always leads to inflation. These monetarists argue that left to itself there is a natural balance between the many actors in the system, and that adding or taking away money will change none of the fundamental elements (employment or output), but only cause inflation or deflation. For them, the state’s role should be to try and keep inflation at a low and stable level in order to avoid the uncertainty and disruption that comes from sudden jumps in prices, and that the state should do this through exercising some control over the amount of money in the system, principally via interest rates.

If the economy was like a pot of money or household budget, policy would be directed towards trying to fill the pot up with as much money as possible. Economic theory would be about working out how best to get money into the pot. However, this clearly isn’t the case.

States can print money whenever they want to and the great debate in economic theory is about whether or not the state should use its power to add money into the system, or if doing so will only cause inflation.

Drawing out the contrast between public understandings and the basics of economic theory shows how far the pot of money narrative is from reality. It’s not just that people don’t understand the technical aspects of how our economy works, but that they have an unquestioned fundamental vision of it as one thing, when it is another.

BRAVE NEW EUROPE has begun its Fundraising Campaign 2021

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over. Please donate here

Be the first to comment