The western media’s failure to report the reality of Gaza didn’t start on 7 October 2023. It’s always been like this. Here’s why journalists won’t tell you the truth about Palestine

Jonathan Cook is the author of three books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and a winner of the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. His website and blog can be found at www.jonathan-cook.net

Cross-posted from Jonathan’s Substack

The past two years have seen a catastrophic failure by western journalists to report properly what amounts to an undoubted genocide in Gaza. This has been a low point even by the dismal standards set by our profession, and further reason why audiences continue to distrust us in ever greater numbers.

There is a comforting argument – comforting especially for those journalists who have failed so scandalously during this period – that seeks to explain, and excuse, this failure. Israel’s exclusion of western reporters, so the claim goes, has made it impossible to determine exactly what is occurring on the ground in Gaza.

There are several obvious rejoinders to this.

First, why would any journalist give Israel the benefit of the doubt in Gaza – as we have done – when it is the party keeping out reporters? The media’s working assumption must be that Israel has excluded us because it has plenty to hide. The obligation must be on Israel to demonstrate that it is acting out of military necessity and proportionately. That cannot be the starting point of western media coverage.

When one party, Israel, denies journalists the chance to report, our default responsibility is to adopt a posture of extreme scepticism towards its claims. It is to subject those claims to intense scrutiny – all the more so when the world’s highest court has ruled that that Israel’s very presence in Gaza is as an illegal occupier, one that should have left the Palestinian territories long ago.

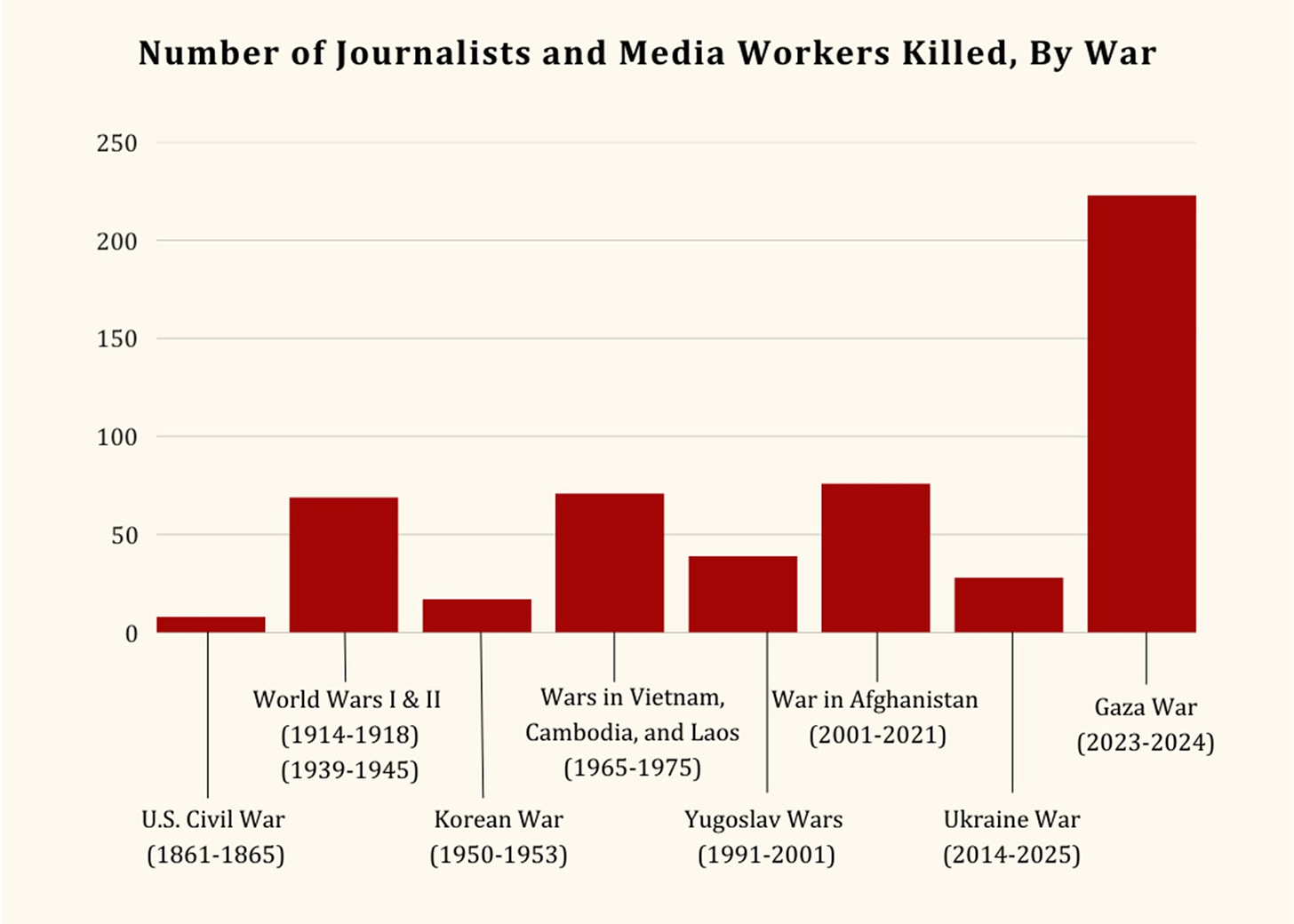

Second, and just as self-evidently, this explanation arrogantly discounts the work of hundreds of Palestinian journalists who have risked their lives to show us precisely what is happening in Gaza. It is to view their contribution, even as they are being slaughtered by Israel in unprecedented numbers, as, at best, worthless and as, at worst, Hamas propaganda. It is to breathe life into Israel’s self-serving rationalisations for murdering our colleagues – and thereby sets a precedent that normalises the targeting of journalists in future conflicts.

It is also to treat these Palestinian journalists with the same colonial contempt demonstrated by British aristocrats a century ago, when they promised away the Palestinians’ homeland to European Jews, as if Palestine was a possession Britain was entitled to dispose of as it saw fit.

And third – and this is the issue I want to grapple with tonight – the presence of western journalists in Gaza would not have made any dramatic difference to the way the slaughter of Palestinians was presented. Audiences would still have received a sanitised version of the genocide. Failure is baked into western media coverage of Israel and Palestine. I know this firsthand from 20 years of reporting from the region.

Career suicide

When it comes to the festering wound in what was once historic Palestine, the job of western journalists is to obfuscate, equivocate, distort and excuse. It always has been. I will get to the reasons why a little later. [If you prefer, you can skip direct to that section under the subhead “Why so craven?”]

Israel has been able to get away with genocide in Gaza precisely because, for the preceding decades, the western media refused to report on – or hold Israel accountable for – its well-documented ethnic cleansing operations against Palestinians, and its brutal apartheid rule over them.

A few of our most principled journalists tried to report these things in real time. But they publicly paid a high price for doing so. Any colleagues who might have thought of following in their footsteps learnt the necessary lesson: that emulating these journalists would be career suicide.

Let me briefly document a couple of distinguished foreign correspondents in Jerusalem who were made examples of, and then provide more recent examples from my own run-ins with western editors.

In the book Publish It Not (1975), Michael Adams, the Guardian’s Jerusalem correspondent in the late 1960s, sets out his struggles to persuade the paper to believe his accounts of systematic Israeli brutality following its military occupation of the Palestinian territories in 1967. His editors, like the rest of the media, preferred to believe Israel’s claim that its occupation was “the most enlightened in history”.

When Adams tried to challenge that assumption, by reporting on Israel’s ethnic cleansing of three Palestinian villages under cover of the 1967 war – the villages were destroyed and would later become a green space for Israelis called Canada Park – he was pushed out of the paper. He recounts that his editor told him “he would never again publish anything I wrote about the Middle East.”

Then there was Donald Neff, Time magazine’s bureau chief in the 1970s. He was eased out after reporting in 1978 on Israeli soldiers savagely beating Palestinian children in Beit Jala, a West Bank community near Bethlehem. It was a very tame story by today’s standards, given that we now have actual footage of Israeli soldiers committing crimes against humanity, often posted on their own social media. But then such a report had the power to shock.

Neff’s bureau staff – all of them Israeli Jews – responded in open revolt to his story. Official Israeli sources refused to speak to him. The Israel lobby in the US began a public campaign against Neff and Time. His editors were unsupportive, and the story was ignored by other US media. Isolated and exhausted from the attacks, Neff left his post.

Becoming an outcast

I only learnt of these distinguished reporters’ troubles some time after I had similar experiences covering the region as a freelance – something I did for 20 years. In my early years, I repeatedly came up against the same editorial pressures and resistance faced by Adams and Neff more than quarter of a century earlier. I felt similarly isolated, besieged, outcast – and eventually abandoned any hope of continuing to report for major western media outlets.

I submitted stories to both the Guardian – where I had previously been a staff journalist for many years – and the International Herald Tribune, now refashioned as the International New York Times.

Let me quickly illustrate an example I had with each.

The Guardian repeatedly shied away from running an investigation I had conducted that revealed how an Israeli sniper had knowingly shot dead a British UN official, Iain Hook, in the West Bank city of Jenin in 2002. I was the only journalist to travel to Jenin to see what had happened. Chris McGreal, the paper’s recently arrived Jerusalem correspondent, lobbied for the story on my behalf. After weeks of stalling, the paper finally, and reluctantly, agreed to run the piece on a full page.

When it appeared, however, it had been cut in half without warning. The heart of the investigation, showing how the sniper had killed Hook, had been removed. Editors claimed they had been forced to take a last-minute ad – something I knew to be impossible, because I had earlier worked in a production role at the paper. They never had any intention of running the investigation. They had duped not only me but their own Jerusalem bureau chief.

At the Tribune, I spent much of the first half 2003 trying to persuade the comment editor to run an oped I had written arguing that the 1,000km steel and concrete wall Israel was building across the West Bank was a land grab, taking vital farm land from Palestinian communities. It seems almost laughable now to imagine that this was a controversial view. But in those days, it was considered controversial even to refer to the separation wall as a wall.

The comment editor finally relented, but only because President George W Bush had just made a speech in which he warned that the wall must not become a land grab. Why the paper had been so frightened to run the story soon became apparent. It received what one junior editor told me was “the biggest post-bag in its history” of complaints. The Anti-Defamation League, a powerful Israel lobby group in the US, had organised a write-in campaign.

Camera, a pro-Israel media lobby group, wrote a pages-long complaint listing 10 supposed “errors” in my oped. I had to hurriedly write a lengthy defence to the editors – more like a minor dissertation, with footnotes – before they agreed not to publish a retraction. However, the paper caved by dedicating its entire letters page to criticism of the article.

Camera and another media lobby group, Honest Reporting, protested every time my name appeared in the IHT. Soon I was out of the door.

I could tell many more such tales.

Media regression

Chris McGreal’s time in Jerusalem in this period was revealing too. He had been a highly distinguished South Africa correspondent for the Independent and the Guardian newspapers during the apartheid era. He won many awards.

He arrived in Jerusalem for the Guardian in 2002 and recognised immediately that Israel was operating a similar apartheid system. However, it was only when he left the post in early 2006 that the paper agreed to publish a lengthy, two-part feature on the similarities between the South African and Israeli varieties of apartheid.

Those two articles are sometimes held up as an example of how the western media can be highly critical of Israel. But that’s not the right conclusion to draw. McGreal’s two pieces were exceptional in every sense.

No paper but the Guardian – and specifically the Guardian of that time – would have run McGreal’s apartheid stories. No journalist other than McGreal would have been allowed to write them. Even so, the paper waited till he had left Jerusalem before daring to publish, knowing that he would become persona non grata, losing all access to Israeli officials.

And once the articles were published, McGreal and the paper faced a torrent of accusations that they were antisemitic. They spent many months fighting a rearguard action to deal with the fall-out.

Let us note this too: The end of the second intifada, in about 2006, was probably a high point for liberal western media outlets like the Guardian in their critical approach to Israel. Why? Because traditional media was struggling to maintain narrative dominance faced with the arrival of media rivals such as al-Jazeera, brought to prominence by the new digital technology. The Guardian felt a need to compete on this new, uncharted digital terrain.

Briefly, the Guardian responded by democratising online, allowing a much wider range of journalistic voices to appear via its “Comment is Free” blog site and giving readers the freedom to comment below articles. Soon those advances would be reversed. The Guardian soon scrapped the blog. It ended comments on any but the tamest articles. And as the digital gatekeepers got wiser, they found an array of covert techniques to crush the new wave of dissent, from shadow-banning to algorithmic manipulations.

Paradoxically, since then, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and Israel’s own B’Tselem human rights groups have all concluded that Israel is an apartheid state. Their verdict is backed by a ruling last year from the International Court of Justice.

But in many ways the western media have actually regressed since the mid-2000s, even as the reality of Israel’s violations of international law have come into ever sharper focus. The media are no readier to refer to Israel as an apartheid state than they were 20 years ago.

Why so craven?

The big question is why. Here is an outline of the various pressures, some practical and others structural, that keep the western media so craven towards Israel.

Partisan reporters: Historically, most publications – especially US outlets – have put Jewish reporters in charge of their Jerusalem bureaux, based on the probably correct assumption that, given Israel’s tribal political ideology of Zionism, Jewish reporters will have better access to Israeli officials. Which, in turn, tells us that these papers are chiefly interested in what Israeli sources have to say, not what Palestinians say. In truth, western media aren’t watchdogs. They don’t challenge the existing power imbalance, they reproduce it.

Many of these Jewish reporters have not hidden their deep attachment and partisanship towards Israel.

Many years ago, a Jewish journalist friend based in Jerusalem wrote to me after I first made this point public, stating: “I can think of a dozen foreign bureau chiefs, responsible for covering both Israel and the Palestinians, who have served in the Israeli army, and another dozen who like [the New York Times’ then bureau chief Ethan] Bronner have kids in the Israeli army.”

Imagine if you can, the New York Times employing a Palestinian as their Jerusalem correspondent – I know, it’s inconceivable. But not just that. Employing them while the correspondent has a child working for the Palestinian Authority, or, even more precisely, one fighting in a Fatah military brigade.

Meanwhile, the BBC openly backs its Middle East online editor, Raffi Berg, even though its own whistleblowing staff have accused him of skewing the corporation’s coverage of Israel and Palestine. Berg has not been shy in admitting his own tribal affiliation to Israel. In an interview about his “insider” book on Israel’s spy agency Mossad, Berg states that “as a Jewish person and admirer of the state of Israel” he gets “goosebumps” of pride hearing about Mossad operations.

Raffi Berg, the BBC’s online Middle East editor, is suing Owen Jones for publishing an investigation in which numerous BBC whistleblowers accused him of skewing news in Israel’s favour.

Here Berg tells an interviewer that “as a Jewish person and admirer of the state of Israel” he gets “goosebumps” of pride hearing about operations by th…

Berg has a framed letter from Benjamin Netanyahu and a photo of himself with the former Israeli ambassador to the UK hanging on his wall at home. He counts a former senior Mossad official as a close friend. And when the journalist Owen Jones wrote a piece revealing the near-revolt of BBC staff at Berg’s role, Berg’s first thought was to seek legal help from Mark Lewis, the former head of UK Lawyers for Israel, well-known for using lawfare as a way to bully and silence critics of Israel.

Can we imagine the BBC appointing a Palestinian or Arab to that same hyper-sensitive post and then supporting them when it emerged that they had a framed letter from the assassinated Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh and a photo with Yasser Arafat hanging on their wall at home?

Partisan bureau staff: It is considered entirely normal for western media to employ partisan Israeli Jews as support staff. As Neff noted, they exert subtle and sometimes not so subtle pressures on correspondents to be more sympathetic towards Israeli narratives.

An investigation by Alison Weir of If Americans Knew found, for example, that in 2004 Israeli staff at the AP news agency’s bureau in Jerusalem had refused either to use or return video footage sent in by a Palestinian cameraman that showed Israeli soldiers shooting an unarmed youth in the abdomen. Instead, they destroyed the tape.

Media lobby groups: Camera and Honest Reporting operate as a pair of media sheepdogs, aggressively herding journalists into line. As I found, they can make your life very hard indeed: they can mobilise large numbers of fanatical Israel supporters to bombard publications with complaints, they can damage your credibility with your own editors, and they can alert Israeli officials to put you on a media blacklist. Most reporters see them as very dangerous organisations to cross.

Access: A general flaw in journalism’s claim to be a watchdog on power – remember, we call ourselves the Fourth Estate – is that reporters invariably need access to high-level officials, whether for stories, steers or comments. A journalist with such a source is seen by editors as far more useful, and reliable, than one without. This is true whether one’s beat is crime, politics, sport or entertainment.

However, access inevitably comes at the price of independence. No one with a high-level source wants to antagonise that source – and lose access – by saying things too critical about the organisation the source has inside knowledge of.

Jerusalem correspondents are possibly even more access-dependent – in their case, on Israeli officials – than other reporters, given that critical stories of Israel are especially likely to lead to official complaints, threats of legal action and loss of access.

Remember, no editor will be keen to run a story critical of Israel before they have given Israeli officials a right of reply. At this stage, Israel, or its lobbyists, can often effectively squash a story. If Israel indicates it will push back hard, making trouble for the publication – or the media outlet assumes it will – editors are likely to pull the story rather than risk a major confrontation.

Pressures from head office: Notice too that media head offices in the US and Europe are subject to another layer of lobby pressure – this time through the lobby’s association of criticism of Israel with antisemitism. Groups like the Anti-Defamation League or the Board of British Deputies are there claiming to represent local Jewish communities, who they report to be “upset”, “frightened”, “bullied” or “anxious” every time Israel is criticised.

Paradoxically, it is hardbitten editors who seem most frightened and anxious. In 2011 the late media academic Greg Philo quoted a senior BBC editor who spoke of “waiting in fear for the phone call from the Israelis”. The priorities of western editors have been all too obvious over the past two years: desperately sensitive to those who support Israel massacring and starving the people of Gaza, while utterly insensitive to those standing in solidarity with Palestinians who are being massacred and starved to death.

The result is that the bar set for publication, if a story is critical of Israel, is far higher than it is for other regions. Just think of how readily journalists attribute atrocities in Ukraine to Russia, compared to how reticent journalists – sometime the same ones – are to identify worse crimes in Gaza as atrocities and name Israel as the responsible party.

Israeli government censorship: It is often not understood that Israel operates a military censorship system that limits what journalists can say. This is especially important given that much of what Jerusalem correspondents write relates to Israel’s illegal military occupation.

In its severest form, that means Israel simply refuses journalists access to areas, as it has done for two years in Gaza. Or it can require them to embed with the Israeli military, as the BBC has done on several occasions during the Gaza genocide. Or it can demand that journalists don’t tell important facts about what is going on.

During Israel’s 2006 war on Lebanon, for example, I was the only journalist who tried to allude, as best I could, to the fact that Israel was stationing tanks firing into south Lebanon inside or next to Palestinian communities, turning the populations there effectively into human shields. Journalists mostly self-censor to avoid running up against Israel’s military censor.

A rare example of a journalist mentioning the censorship system was the BBC’s Lucy Williamson, when she was allowed to embed this month with the Israeli military to film the destruction of Gaza. She observed: “Military censorship laws in Israel mean that military personnel were shown our material before publication. The BBC maintained editorial control of this report at all times.”

And I have a bridge to sell you.

Israeli government control: Israel licenses foreign correspondents by issuing them a Government Press Office card. For the past 20 years, Israel has issued the cards only to journalists formally working for a news organisation it regards as “accredited”. This licensing system was tightened after new digital media platforms offered freelance journalists the chance to reach audiences outside billionaire- and state-owned media. Israel has effectively banned independent, freelance journalists, in an attempt to ensure reporting is filtered through big news organisations whose own limitations I have pointed out above.

Rebuilding our worldview

The practical pressures listed above gain much of their force because journalists and editors have historically been afraid of being accused of antisemitism by Israel. It is tempting to overestimate this pressure. I suspect it is better seen as a cover story, rationalising the failure of journalists to do their job properly – as their reluctance to identify the Gaza genocide as a genocide illustrates.

But beyond these practical pressures, there is a deeper reason for why the western media avoid serious criticism of Israel.

Israel is integral to a continuing western colonial system of power projection into the oil-rich Middle East. Israel is the West’s ultimate client state. Western establishments need Israel protected.

None of this would be so significant, of course, if our celebrated “free press” was, in fact, as free it claims. If it really served as a watchdog on power. If it really held the feet of the political class to the fire. If it really served as a Fourth Estate. Then the politicians would have no place to hide.

But that is not what the corporate media do. Instead, they echo and amplify the political establishment’s priorities. They are, in fact, the media wing of the establishment.

When I was at the Guardian, the foreign editor – now a major columnist – once told me that he did not like his correspondents to spend more than a few years in difficult posts like the Jerusalem bureau because, given time, they were likely to “go native”. At the time I did not understand what he meant. But I learnt soon enough.

I moved to cover the Israel-Palestine beat as a freelance journalist in 2001. I had no editors breathing down my neck. I based myself in Nazareth, a Palestinian community inside Israel, thinking that taking a different approach – my colleagues were in Jewish areas of Jerusalem or in Tel Aviv – would make my journalism distinctive and interesting to editors back home. In fact, my different perspective made me far less interesting to editors. Indeed, as quickly became clear to me, it made them extremely nervous of me.

But the point is this: despite my unique circumstances, it took me years to fully “deprogramme” and emerge the other side relatively whole.

I first had to unravel the conditioning and training – both ideological and professional – that had encouraged me to assume Israelis were the Good Guys and Palestinians … well, they must be something less than the Good Guys.

And then I had to rebuild my ideological and professional worldview from scratch – like a child, trying to make sense of all the new information I was absorbing. Although I hid it at the time, the truth is it was a slow, frightening and painful awakening. Everything I believed in and trusted had crumbled to dust.

Is it any surprise that the vast majority of journalists never make such a transition. They are highly unlikely to have the opportunity to immerse themselves deeply in the lives of those “natives”. They are rarely allowed the time to step off the journalism treadmill to develop a bigger perspective. They are surrounded by family, friends, colleagues and bosses, who constantly reinforce received wisdom or enforce “professional” standards that shore up the existing consensus. They are disincentivised from straying off the path, when they have a salary to earn, a career to develop, bills to pay, a family to feed.

And ultimately, of course, there is the prospect of a terrifying journey ahead, down a dark tunnel to a destination unknown.

All my posts are freely accessible, but my journalism is possible only because of the support of readers. If you liked this article or any of the others, please consider sharing it with friends and making a donation to support my work. You can do so by becoming a paid Substack subscriber, or donate via Paypal or my bank account, or alternatively set up a monthly direct debit mandate with GoCardless. A complete archive of my writings is available on my website. I’m on Twitter and Facebook.

Be the first to comment