The EU has not had many successes in the past decade. In such times one has to fabricate these, as here in the case of Spain.

Nacho Álvarez is associate professor at the Autonomous University of Madrid and responsible for Podemos’s economic team (@nachoalvarez)

Jorge Uxó is associate professor at the University of Castilla la Mancha and a member of the Podemos economic team

In the international media we read repeatedly of the supposed “Spanish miracle”. The Spanish economy has been growing again for several years now, and it is growing significantly faster than other euro-zone economies.

International financial institutions and the European Commission are trying to disseminate the message that fiscal austerity and labour market flexibility have proved successful in Spain. But that message is untrue, and it ignores some of the following fundamentals.

Firstly, the fiscal and wage cuts imposed by Brussels prolonged the economic crisis needlessly by reinforcing its depressive effect. It was precisely these cuts – as of 2010 – that determined the second phase of the crisis. The insistence, by the government of prime minister Mariano Rajoy, on policies between 2012 and 2014 that reduced the level of domestic demand, meant that Spain lost a decade of growth: it has taken ten years for the country to reach the level of GDP per capita it had before the crisis, and it has only recovered half of the jobs that were destroyed during that period.

Moreover, wage cuts and fiscal austerity have not only failed to drive the recovery, they have also deepened other problems. They have increased social inequality, eroded key public services and delayed public investment, including in research and development.

Secondly, the factors that explain the economic growth of recent years should be analysed carefully. Indeed, the Spanish economy is growing at 3% in annual terms, approximately one point above the euro-zone average. But, that is not the result of either wage cuts or fiscal austerity.

The deregulation of the labour market has supposedly boosted recovery in two ways. . According to the analyses of the European Commission and mainstream economists, lowering the cost of severance pay and cutting wages should have translated into greater job creation, boosting private consumption. Furthermore, labour reforms implemented in previous years should have increased Spain´s price-competitiveness and led to a recovery driven by the export sector.

But the reality of the Spanish economy does not confirm either of these two policies. To begin with, labour reforms have not displaced the Okun curve: the relationship between the rate of job creation and economic growth has not changed, so that in periods of economic growth our economy continues to create jobs rapidly – of poor quality – only to destroy them just as rapidly in times of crisis. That is, there is no trade-off between employment and wages.. What has happened in recent years, however, and this is probably the main effect of the labour reform, is that collective bargaining has become rebalanced in favour of companies, and the new jobs created set wages even lower. The duration of contracts has also been greatly reduced and the quality of jobs has deteriorated.

Moreover, the idea that wage devaluation has generated competitiveness gains and an export boom cannot be substantiated. The rate of growth of exports during the period 2010-2017, although significant, is very similar to the one we had in 2000-2007, despite the fact that relative labour costs were increasing at the time. The main reason for this is that the development of exports basically depends on external demand. Wage reductions have hardly translated into a reduction in relative export prices. This reduction in wages has been squandered and simply gone to increasing the profits of exporting companies.

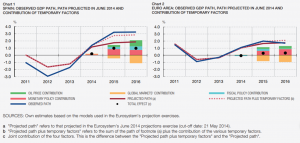

Other factors explain the recent rapid growth of the Spanish economy. In its Annual Report for 2017, the Bank of Spain attributes much of the faster growth in 2015-16 to the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) monetary policy and the sharp fall in oil prices. Both factors are beyond the reach of government policy. According to the Bank of Spain these factors explain about half of the additional growth experienced by the Spanish economy during the actual recovery (Figure 1).

Figure 1: GDP in Spain and in the Euro area (Annual rates of change)

Source: Bank of Spain, Annual Report 2016, pp: 48.

These “tailwinds” do not affect all the economies of the euro zone equally; they have a greater impact on our economy. This is because Spain is a country with a comparatively high level of household and corporate debt, and with a large portion of mortgages tied to Euribor (a floating rate of interest). It is therefore understandable that reductions in interest rates affect Spain – through private household consumption and investment – more than other euro zone countries. Furthermore, Spain is known for its traditional dependence on fossil fuels. The price of oil has a greater impact on the cost structure of the Spanish productive sector than in the surrounding countries. In fact, if it were not for the low oil prices, Spain’s current-account balance would already be suffering as it usually does in periods of expansion.

But, there is a significant additional growth factor. During the period 2015-2017, not only did the Spanish government enjoy these favourable tailwinds, it also interrupted the harsh fiscal cuts of previous years, even promoting – incidentally in the middle of the electoral period, and with the acquiescence of the Brussels institutions – a cautiously expansive fiscal policy. This fiscal policy resulted in up to 0.5 percentage points of additional annual growth during the period.

Finally, and despite the elements described, it is very difficult to talk about “economic recovery” today in Spain. The characteristics and profile of current growth reveal enormous structural problems. How can we talk of economic recovery when more than a third of the population is excluded from the benefits of this growth, and employment is no longer a passport to all the benefits of civic life for a large number of workers? Isn’t the current growth based once again on very weak foundations: harsh inequality, precarious employment, low wages, abuse of the environment and lack of transition to renewable energy sources?

Of the 1.5 million net jobs created in the period 2015-2017, around two-thirds have been temporary. The latter have an average annual salary of 10,000 euros lower than those in permanent employment. Spain’s temporary employment rate is now twice that of Germany, Greece or Denmark and, whereas in 2007 the average duration of contracts was 79 days, in 2018 it was reduced to 53 days. Today only 50% of unemployed people have access to social benefits (this figure was 70%, before prime minister Mariano Rajoy came to power).

These data indicate that talking about “recovery” requires going beyond mere income and employment levels and focusing on other dimensions: quality of growth and employment, income distribution and sustainability.

A profound change in economic policy is needed. A new fiscal policy must help to strengthen current growth – which is too dependent on tailwinds – and job creation. At the same time, a new economic plan must also have as its prime objective the transformation of growth itself, reducing the enormous current socio-economic inequalities, focusing efforts on an industrial policy that improves productivity, and promoting a process of energy transition that reduces our dependence on fossil fuels.

These challenges require a fiscal policy that definitively abandons austerity -even of the “soft” variety-, that is a policy that reverses the cuts of this disastrous lost decade and undertakes the necessary investments to promote industrial change and the reduction of inequality.

But these policies must also allow the benefits of growth to be distributed among the entire population (a significant increase in the minimum wage, a plan to combat temporary employment, the pre-eminence of sectoral collective agreements over company agreements, and the re-linking of pensions to price increases).

In the absence of these changes, the “recovery” model called for by Brussels will widen the social divide, postpone energy transition, and continue to base growth on the weak foundations of the past. A recovery that condemns one-third of the country to exclusion from increased prosperity calls into question the very pillars of our democracy. Our nation, including its economy, urgently needs a course correction.

Be the first to comment